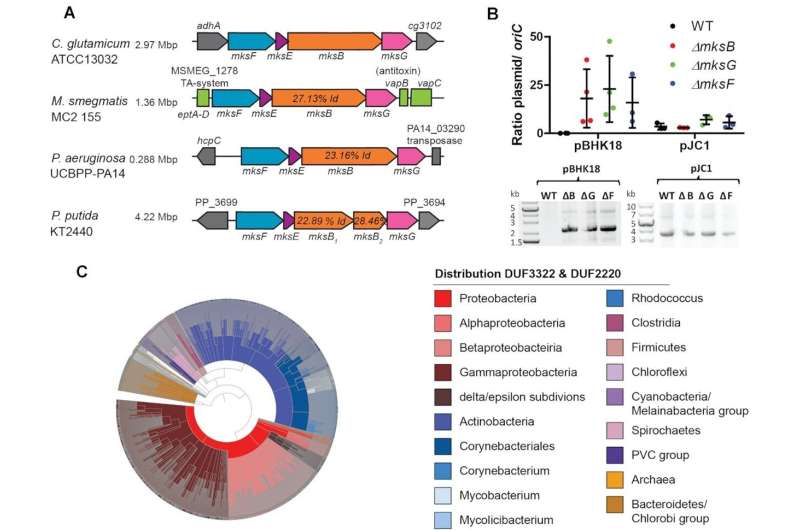

MksBEFG- defense system is widespread. (A) Representation of the mksFEBG-operon organization from different organisms: (i) C. glutamicum ATCC13032, (ii) M. smegmatis mc2 155, (iii) P. aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 and (iv) P. putida KT2440. (B) Plasmid copy numbers of low copy (pBHK18) and high copy number plasmids (pJC1) relative to oriC numbers per cell, assayed by qPCR. Ratios were compared between C. glutamicum WT (MB001), ΔmksB, ΔmksG, ΔmksF cells grown in BHI medium with selection antibiotic (mean ± SD, n = 3). Plasmids pBHK18 and pJC1 were extracted from C. glutamicum WT, ΔmksB, ΔmksG, ΔmksF cells grown in BHI medium with antibiotic selection, visualization of extracted DNA on 0.8% agarose gels. (C) Phylogenetic analysis of MksG-like proteins (organized in DUF3322 and DUF2220 domains) using the SMART platform reveals the distribution among Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and archaea. Credit: Nucleic Acids Research (2023). DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkad130

A research team from Kiel University describes an unknown defense mechanism in bacteria that selectively wards off foreign and potentially harmful genetic information.

Since the coronavirus pandemic, the particularly rapid evolutionary adaptability of microorganisms such as bacteria or viruses has been brought into the public spotlight. For example, when viruses develop the ability to infect new host organisms or bacteria develop antibiotic resistance, the uptake of new genetic information from other microorganisms allows them to quickly express evolutionarily advantageous traits.

Bacteria, for example, take up foreign DNA through a process called horizontal gene transfer, which is much faster than the vertical inheritance from generation to generation.

However, every living organism also faces risks by taking up foreign genetic information, as it could potentially be dangerous if, for example, important genes are damaged by integration into its own chromosome, resulting in major disadvantages for the organism as a whole. Therefore, bacteria have developed numerous mechanisms protecting them from absorbing harmful DNA. Many of the molecular processes involved were discovered in recent years, leading to the recent coinage of the term "bacterial immune system."

Now, a team from the Microbial Biochemistry and Cell Biology Group at the Institute of General Microbiology at Kiel University has elucidated the function of a new defense mechanism that can identify and, if necessary, break down certain independent and mobile DNA structures called plasmids in bacterial cells—while distinguishing between useful and harmful genetic information.

Using the bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum as an example, the researchers showed that the so-called Mks protein system has an additional element that can bind to plasmid DNA and cut it apart. The Kiel scientists led by Professor Marc Bramkamp published their new results in Nucleic Acids Research.

Proteins for DNA organization can also defend against plasmids

Plasmids are small, usually ring-shaped, double-stranded DNA molecules that can replicate independently of the chromosome in their host cell. They play an important role in the ecology and evolution of bacteria, as they are an important vehicle of lateral gene transfer, enabling the rapid transfer of genetic information and thus the expression of selection advantages. In principle, all bacteria can exchange plasmids with each other even across species.

This happens directly from bacterium to bacterium via a transfer mechanism known as conjugation. Both advantageous and disadvantageous plasmids utilize such bridges between bacterial cells to switch from one bacterium to another.

"How the bacterial organism deals with foreign DNA from newly transferred plasmids has been little researched so far," Manuela Weiß, Ph.D. student in Bramkamp's research group points out. "In previous research, we have investigated systems that are generally involved in the organization of DNA in bacterial cells and, among other things, ensure the packaging of genetic information into the compressed form of chromosomes," Weiß continues.

In this context, the research team obtained initial indications that C. glutamicum possesses two such systems, one of which is not involved in the organization of the chromosome, but can prevent the multiplication of certain plasmids, although the mechanism responsible for this was previously unknown.

Now, the Kiel researchers, together with experts led by Dr. Anne Marie Wehenkel from the Institut Pasteur in Paris, have discovered the DNA scissors of the Mks system in a structural study. "We were able to prove experimentally that this new subunit of the Mks system forms a specific protein, a so-called nuclease, which can cut DNA. This element has the task of degrading plasmids in order to keep harmful DNA away from the bacterial cell, while the other components of the Mks system are important for the recognition of plasmid DNA," Weiß says.

Distinguishing between useful and harmful plasmids

The researchers then followed up on the observation that the Mks system apparently only degrades certain plasmids and that it must therefore be linked to a selection mechanism. An important advantage here is that Bramkamp's research group is working with the bacterium C. glutamicum, an organism that naturally possesses this system. Its functions can therefore be studied in vivo without its cell biological properties being altered by transferring it into a model system.

"Bacteria use certain plasmids as a source of new, not immediately vital, genetic information. It is therefore obvious that a defense mechanism must be selective and not destroy all plasmids," says Bramkamp.

"We were able to prove that in C. glutamicum there is indeed a directed selection according to beneficial and detrimental genetic information. When we artificially switched off the Mks system and thus all plasmids remained in the bacterial cells, detrimental effects on the cell, possibly triggered by DNA stress, were evident. However, these did not occur when the defense mechanism was active," Bramkamp continues.

With the current work, the Kiel researchers are presenting important new findings about the bacterial immune system overall, which expand the understanding of plasmids as mediators of not only beneficial but also harmful genetic information. In future, they want to investigate which molecular mechanisms allow bacterial cells to differentiate between "good" and "bad" mobile DNA.

The new results are not only important for the general understanding of the organization and reproduction of bacterial life. The increasingly precise investigation of the bacterial immune system could also help to better meet applied challenges—and, for example, to better model and predict the evolution of antibiotic resistance in certain bacterial populations in the future.

More information: Manuela Weiß et al, The MksG nuclease is the executing part of the bacterial plasmid defense system MksBEFG, Nucleic Acids Research (2023). DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkad130

Journal information: Nucleic Acids Research

Provided by Kiel University