Researchers report that in each organism, longer chromosome arms are always wider. Credit: Dr. Yasutaka Kakui from Waseda University

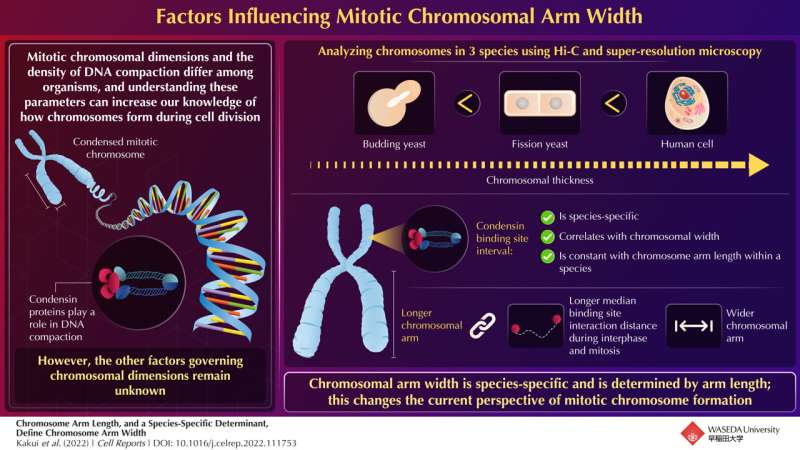

Chromosomes are a highly condensed form of DNA and are crucial for cell division. During mitosis, chromosomes ensure that genetic material is equally divided among the daughter cells. Interestingly, the dimensions and degree of DNA condensation in mitotic chromosomes vary from organism to organism. How this is regulated—i.e., what factor governs mitotic chromosomal formation and dimensions—remains a mystery.

A team of researchers led by Dr. Yasutaka Kakui from Waseda Institute for Advanced Study, Waseda University; Frank Uhlmann at the Chromosome Segregation Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute; and Toru Hirota, from the Division of Experimental Pathology, Cancer Institute of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, set out to decode this enigma.

How did it all start? For Kakui, it was his fascination for chromosomes that motivated him to take up this research. "How is genomic DNA stored within cells? This is an ancient, unsolved question. To expand our knowledge of how cells accurately pass on genetic information to successive generations, we need to understand the molecular basis for chromosome formation." And that is what drove this study, the findings of which have been published in Cell Reports.

During mitosis, DNA undergoes significant compaction to form chromosomes. A large protein ring complex called condensin plays a key role in the compaction process. It binds at specific sites on DNA and compresses it by forming loops. So, scientists know that condensin is crucial for DNA compaction, which is closely related to chromosomal dimensions—with thicker chromosomes being more compacted. They also know that the pattern of condensin-binding sites is species-specific. But the exact role of condensin and chromatin contacts in determining chromosomal dimensions is, as yet, unclear.

The researchers explored various facets of condensin and chromatin contacts to address the questions at hand. They employed Hi-C and super-resolution microscopy to analyze the correlation between mitotic chromatin contacts and chromosomal arm length in both budding and fission yeasts, S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, respectively.

Conclusive evidence was found indicating that the distance between chromatin contacts is directly proportional to arm length in both interphase and mitosis. Hence, shorter arms have short range contacts and longer arms have long range contacts. This was found to be species-specific.

Now, longer distances of chromatin contacts lead to larger chromatin loops, both of which are indicators of wider chromosomal arms. The authors thus investigated both budding and fission yeasts to conclude that within a species, longer chromosomal arms were always wider. Motivated by the successful observation in the yeasts, they extended their study to human cells, to find the same correlations.

"We made the unexpected discovery that longer chromosomal arms are always thicker throughout eukaryotic species, which helps us understand how mitotic chromosomes form during cell divisions," explains Kakui. Their study would be the first to conclusively establish that chromosomal arm length determines mitotic chromosome width.

This study has provided unique insights into mitotic chromosomal structure that challenge the current perspectives on mitotic chromosome formation. Kakui summarizes, "Our findings would open a novel way to avoid chromosome miscarriage, a probable cause for the formation of cancer cells and/or birth defects such as Down syndrome, through controlling mitotic chromosome structure. This can potentially change medical treatments for cancer therapy and/or fertility treatments."

More information: Frank Uhlmann, Chromosome Arm Length, and a Species-Specific Determinant, Define Chromosome Arm Width, Cell Reports (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111753. www.cell.com/cell-reports/full … 2211-1247(22)01636-9

Journal information: Cell Reports

Provided by Waseda University