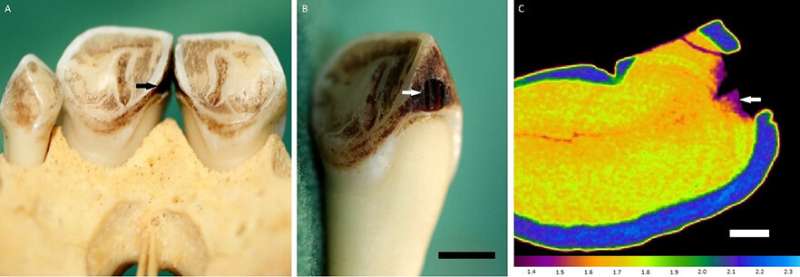

Dental decay on the upper right central incisor in a Dent’s mona monkey. Credit: University of Otago

Tooth decay is a common and unfortunate problem for many of us, but two University of Otago studies show it is also an issue for other primates, as well as our fossil relatives and ancestors.

Dr. Ian Towle, the former Sir Thomas Sidey Postdoctoral Fellow in Otago's Faculty of Dentistry, says cavities are often considered to be a modern disease unique to humans, related to a diet rich in processed sugary foods. However, he says there is growing evidence tooth decay also occurs to a certain extent in other animal groups.

"Our new research shows caries also occurs in wild primates in low frequencies, although this is highly variable among groups and the teeth affected also vary," he says.

"This research helps us understand changes in diet and behavior in human evolution; it also provides insight into particular behaviors in our living primate relatives."

For the research, published in the American Journal of Primatology and South African Journal of Science, Dr. Towle and colleagues analyzed more than 8,000 extant primate and fossil human teeth and assessed variation in tooth decay patterns in relation to diet and behavior.

They found 3.3 percent of teeth in living primates had caries, which is similar to the incidence in fossil humans (ranging from 1 to 4 percent of teeth in different species). However, all caries in the fossil humans samples studied were on back teeth, whereas the vast majority in living primates were on the front teeth.

"The fascinating feeding behaviors of animals such as chimpanzees, using their large front teeth to help suck sugary liquid out of figs, contributes to creating caries patterns rarely seen in humans.

"Indeed, in humans our back teeth are mostly affected by dental decay, whereas in other primates it's typically the front teeth," Dr. Towle says.

Another interesting aspect of this research was that female chimpanzees had more caries than males (9.3 percent compared to 1.8 percent), with similar sex differences often evident in humans.

The work also revealed how similar decay patterns between captive primates and humans are, highlighting how primates often don't undertake specific natural behaviors in captivity.

"Caries occurred throughout human evolution and that doesn't seem to change much for millions of years, with less than 5 percent of teeth affected. However, with the onset of agriculture, this increased rapidly to more than 20 percent of teeth having cavities in some samples."

This study is part of a larger body of work Dr. Towle and colleagues have undertaken into the teeth of primates and human ancestors, mentored by Dr. Carolina Loch, of Otago's Faculty of Dentistry.

"I hope this particular part of the research will help the public understand how living primates have complex and varied feeding behaviors, yet share this common disease with us.

"Tooth decay has the potential to offer unique ecological insight into extinct primate groups," Dr. Towle says.

More information: Ian Towle et al, Dental caries in wild primates: Interproximal cavities on anterior teeth, American Journal of Primatology (2021). DOI: 10.1002/ajp.23349

Ian Towle et al, Dental caries in South African fossil hominins, South African Journal of Science (2021). DOI: 10.17159/sajs.2021/8705

Journal information: American Journal of Primatology

Provided by University of Otago