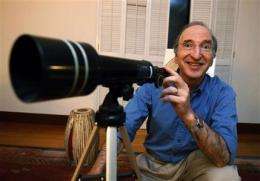

Nobel Prizes winner for physics Saul Perlmutter smiles as he poses with his daughter's telescope at his home in Berkeley, Calif., Tuesday, Oct. 4, 2011 after hearing he had won. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said American Perlmutter would share the 10 million kronor ($1.5 million) award with U.S.-Australian Brian Schmidt and U.S. scientist Adam Riess. Working in two separate research teams during the 1990s, Perlmutter in one and Schmidt and Riess in the other, the scientists raced to map the universe's expansion by analyzing a particular type of supernovas, or exploding stars. (AP Photo/Paul Sakuma)

Saul Perlmutter won the Nobel Prize in physics Tuesday, but it wasn't until the California scientist was awakened by a telephone call from a reporter in Sweden that he learned of the distinction.

"How do I feel about what?" the 52-year-old Perlmutter remembered asking the reporter before dawn from his Berkeley home.

His wife looked online and told him it wasn't a hoax.

"Nobody really expects a Nobel Prize call," Perlmutter told The Associated Press by telephone shortly after the announcement in Stockholm.

Perlmutter was one of three U.S.-born scientists who won the prize for a study of exploding stars that discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

The finding overturned a fundamental assumption among astrophysicists that gravity was slowing the rate of expansion, and that scientists might be able to predict when the universe would come to an end.

"The result was nothing that we expected," Perlmutter, who heads the Supernova Cosmology Project at the University of California, Berkeley, said during a morning teleconference with reporters.

Perlmutter's research relied on massive cosmic explosions called supernovas to serve both as interstellar distance markers and a way to gauge which direction the universe was moving and how fast.

Instead of gaining clues to when the universe would begin contracting rather than expanding, he discovered that the universe was still growing, and at a faster rate.

But Perlmutter said he didn't immediately trust his results. Instead, he thought continued data analysis would eventually bear out that the universe's rate of expansion was decreasing. But months later, it became clear that wasn't the case.

"That was the extended four months of `aha,'" he said. "That's got to be the slowest `aha (moment)' you've ever heard."

Perlmutter also explained that The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awarded the prize, was slow to contact him because it was calling the wrong cellphone number. The academy got that number from a Swedish colleague of Perlmutter's, who didn't realize it was outdated, Perlmutter said.

"They tried to reach me for 45 minutes before going through another route," he said.

Perlmutter will share the $1.5 million award with U.S.-Australian Brian Schmidt and U.S. scientist Adam Riess, according to the acadmey, which credited their discoveries with helping to "unveil a universe that to a large extent is unknown to science."

Asked how he would spend the money, Perlmutter said he hadn't had time to think about that yet. He spent the morning on the phone and appeared at a news conference later in the day at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

"We knew Saul would win it one of these years," said Paul Preuss, a spokesman for the laboratory. "We just didn't know it would be this year. We are, of course, elated."

In addition to his prize money, Perlmutter will also get one of the coveted reserved parking spaces on campus that UC Berkeley gives to its Nobel winners.

"Which of course is the only reason to win a Nobel Prize, to be able to park on campus," Perlmutter joked.

The award was the 22nd Nobel Prize received by a UC Berkeley faculty member. The first was nuclear physicist Ernest O. Lawrence, whose name graces the national lab where Perlmutter works.

©2011 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.