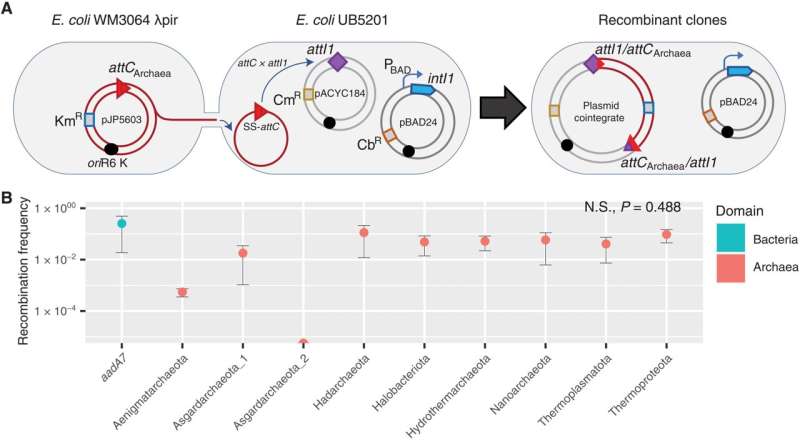

Cassette recruitment (attC × attI recombination) assays. (A) Schematic outlining the experimental setup of the cassette insertion assays. The kanamycin resistance (KmR) suicide vector pJP5603 with an attC site is delivered into the recipient E. coli UB5201 strain via conjugation. The recipient strain carries an intI1 gene, expressed from the inducible PBAD promoter, and an attI1 site, residing on the carbenicillin resistance (CbR) pBAD24 and chloramphenicol resistance (CmR) pACYC184 backbones, respectively. The donor suicide vector cannot replicate within the recipient host and thus can only persist following attC × attI recombination to form a plasmid cointegrate. (B) Average recombination frequencies (log10 scale, ±1 SE) between attI1 and nine archaeal attCs (with phyla of origin labeled along the x axis) and the paradigmatic bacterial attC site (attCaadA7), used as positive control. Average frequencies were calculated following three independent cassette insertion assays (see Materials and Methods for details). No statistically significant difference in recombination frequencies were detected among the tested attCs (Kruskal-Wallis test, n = 27; df = 8, P = 0.488). Recombination frequencies are shown for attC bottom strands only. See table S1 for attC top strand recombination frequencies. N.S., not significant. Credit: Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq6376

A team of researchers at Macquarie University, in Australia, has found evidence showing that some Archaea have integrons. In their paper published in the journal Science Advances, the group describes how they used a recently developed technique called metagenome-assembled genomes (MAG) to study the genomes of Archaea samples in a new way, and what they learned by doing so.

Life on Earth is divided into three domains, Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea. The third domain, Archaea, is similar to Bacteria—its members are often called Archaebacteria. Like Bacteria, Archaea are single-celled but unlike Bacteria, they rely on lipids in their cell membranes.

In this new effort, the researchers were looking into the means by which Bacteria and Archaea swap genes and wondered if it was possible that they have integrons—gene capture and dissemination systems in Bacteria that use gene cassettes to pass the proteins involved. To find out, they turned to MAG—a technique that allows for searching for single gene and gene recombination sites called AttC that sequence for coding the protein integron integrase (IntI).

Using the technique, they found many matches. Of 6,700 genomes scanned, they found 75 matches, across nine phyla, each evidence of an integron. And all of them turned out to have the same structure as the integrons found in Bacteria, which suggested the use of cassettes.

The researchers believed that this indicated that the Archaea they identified should be able to swap genes with Bacteria and vice-versa, as easily as Bacteria swap genes among themselves. To prove that their idea was correct, they synthesized AttC from an Archaea specimen and exposed it to an E. coli specimen. Testing showed that cassettes had been created allowing gene swapping to occur.

Finding integrons in Archaea will most certainly open up new avenues of research. One routed would be to look into the possibility that swapping genes from Archaea to Bacteria help the latter to become resistant to drugs meant to kill them. The researchers also note that it would be helpful if a complete genome of Archaea were made available.

More information: Timothy M. Ghaly et al, Discovery of integrons in Archaea: Platforms for cross-domain gene transfer, Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq6376

Journal information: Science Advances

© 2022 Science X Network