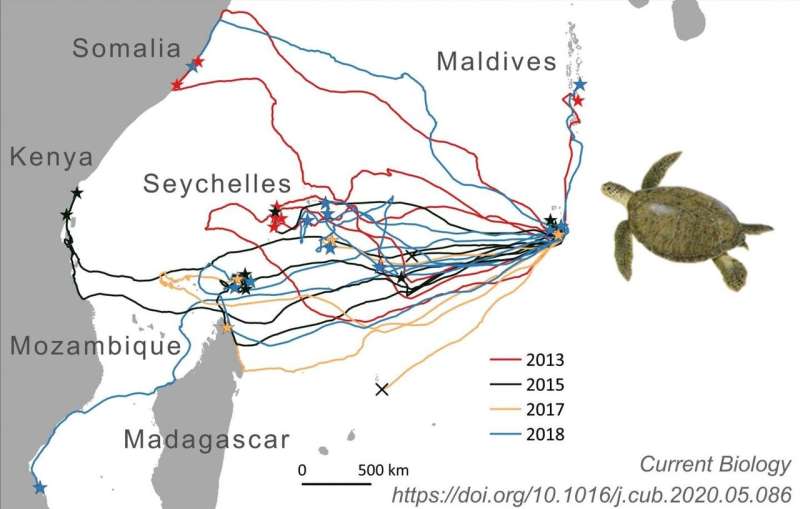

The routes of 35 adult female green turtles traveling to their foraging grounds in the Western Indian Ocean after the end of the nesting season on Diego Garcia, Chagos Archipelago. Turtles tracked in different years are indicated by different colors. Stars = final foraging site, crosses = turtles not tracked all the way to their foraging grounds. Credit: Nicole Esteban, Swansea University

One of Charles Darwin's long-standing questions on how turtles find their way to islands has been answered thanks to a pioneering study by scientists.

A team from Deakin University, University of Pisa and Swansea University equipped 33 green sea turtles with satellite tags and recorded unique tracks of green turtles migrating long distances in the Indian Ocean to small oceanic islands.

The study provides some of the best evidence to date that migrating sea turtles have an ability to redirect in the open ocean, but only at a crude level rather than at fine scales.

Seven turtles traveled only a few tens of kilometers to foraging sites on the Great Chagos Bank, six traveled over 4,000km to mainland Africa, one to Madagascar, while another two turtles ventured north to the Maldives.

Most of the species tracked (17) migrated westward to distant foraging sites in the Western Indian Ocean that were associated with small islands.

It shows that the turtles can travel several hundred kilometers off the direct routes to their goal before reorienting, often in the open ocean.

In 1873, Charles Darwin marveled at the ability of sea turtles to find isolated islands where they nest. However, the details of how sea turtles, and other groups such as seals and whales, navigate during long migrations remains an open question.

Animated tracks of 35 green turtle migrations tracked from nesting beaches in the Chagos Archipelago (Indian Ocean). The year of migration is indicated by colors; red = 2012, black = 2015, orange = 2017 and blue = 2018. Stars (n=33) indicate migration endpoints and incomplete migrations (n=2) are denoted by black crosses. Animation timing has been adjusted so that turtles from all years depart nesting beaches at the same time and migration duration in days is indicated by the counter in the lower right hand corner of the video frame. Of 35 equipped turtles, 33 were tracked all the way to their foraging grounds. The animation highlights the often circuitous routes of individual turtles. Credit: Nicole Esteban, Swansea University

Answering this question using free-living individuals is difficult due to thousands of sea turtles being tracked to mainland coasts where the navigational challenges are easiest.

The study also showed that turtles frequently struggled to find small islands, overshooting, and/or searching for the island in the final stages of migration.

These satellite tracking results support the suggestion, from previous laboratory work, that turtles use a crude true navigation system in the open ocean, possibly using the world's geomagnetic field.

Swansea University's Dr. Nicole Esteban, a co-author in the study said:

"We were surprised that green turtles sometimes overshot their ultimate destination by several hundred kilometers and then searched the ocean for their target. Our research shows evidence that turtles have a crude map sense with open ocean reorientation."

More information: Jeanne A. Mortimer et al. Estimates of marine turtle nesting populations in the south-west Indian Ocean indicate the importance of the Chagos Archipelago, Oryx (2020). DOI: 10.1017/S0030605319001108

Provided by Swansea University