Exploring the work of Professor Judith Kelley. Credit: Duke University

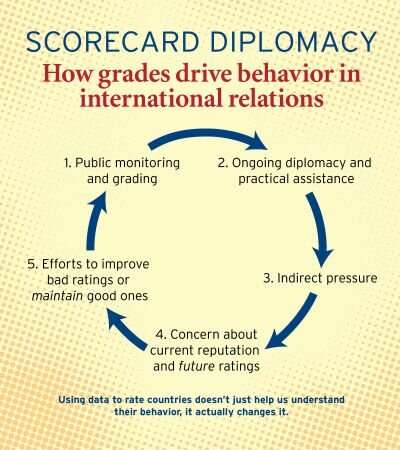

Using data to rate countries doesn't just help us understand their behavior, it actually changes it.

For Judith Kelley, the acronym GPA means more than "grade point average," the term most familiar to her students. She also thinks of "global performance assessments"—public measures of performance that nations, nongovernmental organizations and private entities use to attract attention, shape debate, and—they hope—change behavior.

Kelley studies how international actors influence domestic politics. "What can we do to get countries to stop mistreating people?" she asks.

She has written books on getting states to respect the rights of ethnic minorities, and about how to promote better elections. Her work on international election monitors showed that observing and reporting on elections could improve election quality. Social scientists are familiar with the phenomenon, called the Hawthorne effect: When people are aware they are being observed, they change their behavior.

Yet observation alone may not suffice to bring about desired changes. What other strategies can be used on the international stage to ensure fair elections or secure basic human rights?

"Professors know very well that grades affect behavior," says Kelley. "It can be a motivating tool. A low grade can spur improvement and a high grade can inspire the student to work hard to keep that grade. Nations that care about their reputations can also be influenced through ratings and rankings in what I call 'scorecard diplomacy.'"

Scorecard diplomacy is an important new tool in international relations. It is a form of "soft power," used in combination with, or instead of "hard power," such as economic sanctions or military force. It combines both "carrots and sticks." A bad ranking can shame countries, but scorecard diplomacy goes further than just calling out failures. It also outlines actions that can lead to a better score in the next cycle.

Credit: Duke University

"The essential feature of GPAs is the itchy feeling they create of being socially watched, judged and especially compared with peers," Kelley, and co-author Beth Simmons (University of Pennsylvania) write. Once people realized this type of information was powerful, more organizations began doing it as a way of setting norms.

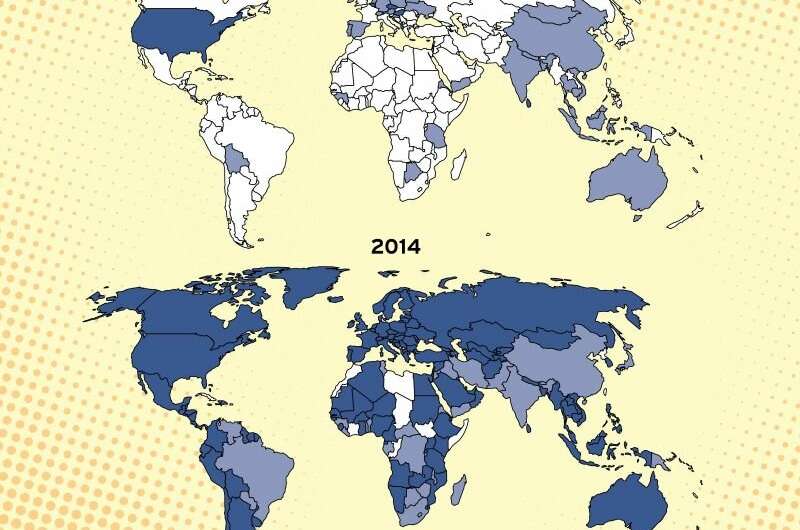

Exploding GPAs

Now that new forms of information technology have made it possible to analyze and spread data globally, instantly, and at a minimal cost, these types of GPAs have exploded. For example, the World Bank has the Ease of Doing Business Index, the NGO Transparency International has the Corruptions Perceptions Index, and the U.S. Department of State has the Trafficking in Persons Report. Indices and rankings exist now in nearly every domain, from gender equality to military power.

Kelley's current research focuses on scorecard diplomacy and human trafficking. Data is unreliable, but the International Labour Organization estimates there are about 20 million victims worldwide. Trafficking is "not only a horrific crime, but it is difficult to combat," she says.

Anti-trafficking measures are costly and countries often deny the problem. Policymakers may not see human trafficking victims as constituents, as the victims are often children, immigrants or part of marginalized groups. Governments may even be complicit in exploitation of workers, such as Japan's worker trainee program, or Uzbekistan's cotton production program. Cultural norms may lead to different ideas of what constitutes trafficking. In the Middle East, foreign children as young as four were formerly bought to serve as jockeys in camel races.

In 2000, two important developments occurred in the global fight against human trafficking. First, the United States passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which established the State Department's Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. Second, the United Nations adopted the Palermo Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons. It established a definition of human trafficking that included sexual exploitation, forced labor and organ removal.

The United States issued its first Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report in 2001. It covers three areas of action: protecting victims, prosecuting traffickers and preventing trafficking. The best ranking, Tier 1, is given to countries that make efforts to address the problem. The worst offenders are graded as Tier 3. There is also a Tier 2, and a "watch list" Tier 2 sub-category, which serves as a warning to those at risk of a Tier 3 grade.

Credit: Duke University

Combined with a U.N. protocol and new web-based reporting platforms, conditions were ripe for the exercise of this type of power. U.S. diplomats combine the public release of the report with quieter forms of diplomacy. These include the use of grants, the possibility of sanctions—so far rather ignored— and collaboration with nongovernmental and intergovernmental organizations.

How well does it work?

U.S. scorecard diplomacy on human trafficking offers a unique opportunity. Not only can Kelley explore the central question of influence in international relations, she also can assess a contested diplomatic effort on an important topic.

Kelley is finding confirmation of the effectiveness of scorecard diplomacy from an unexpected source: WikiLeaks. The archive includes a quarter-million diplomatic cables from 2000 to 2010, a treasure trove of data usually unavailable to scholars.

"The availability of the U.S. State Department cables allows us to peek behind the scenes to understand how officials react in private conversations with the U.S. embassy officials," she writes.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, Kelley identified and analyzed more than 8,500 cables that discussed human trafficking. She also interviewed 90 people from NGOs and IGOs, as well as U.S. politicians and bureaucrats. Kelley complied a database of NGOs working on trafficking, and surveyed 500 of them.

The analysis showed that countries were very concerned with their reputations, especially how they ranked within a peer group and who they were compared with.

Credit: Duke University

A French official noted, incredulously: "You're telling me that France could easily be in Tier Two, with Nigeria?"

Some nations even hired public relations firms to help improve their image. Countries in the bottom tier were more likely to pass anti-trafficking laws in an effort to improve their rankings, Kelley found.

As any teacher knows, disappointed students frequently contest grades. Similarly, countries have accused the United States of arrogance and meddling in their internal affairs. In 2006 Belize's Prime Minister Said Musa said on the evening news: "But those who seek to judge us should perhaps examine their own decadent societies before they come and pass judgment on us."

Countries in Tier 3 or on the Watch List often try to save face by criticizing the validity of the rankings, Kelley says. Sometimes they have good cause, she admits. The policy is not perfect. Nonetheless, it has been effective. Numbers, rating and rankings provoke countries' concern for their international reputations and this, she argues, shows the power of strategically deployed information.

"Scorecard diplomacy uses reputation like a sculptor might use a chisel. By using it to target his force, the sculptor delivers his power more effectively than the use of his hammer alone," says Kelley.

Provided by Duke University