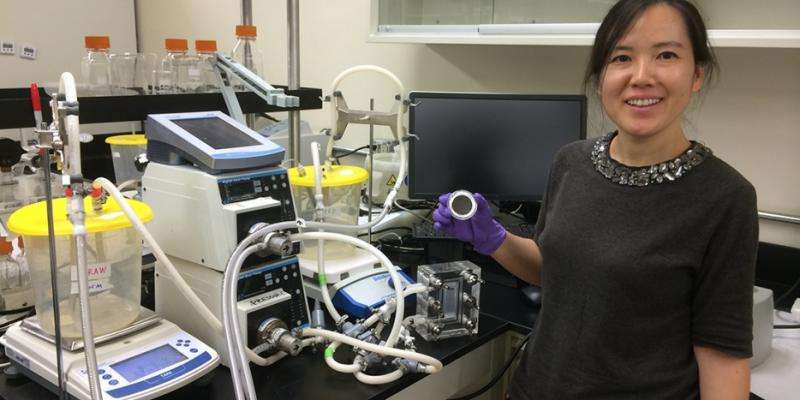

Baoxia Mi at work in her new Davis Hall lab. Credit: Kristine Wong

Growing up in China in the 1980s, Baoxia Mi recognized that water was not something to take for granted.

"When my parents were young, there were many rivers and small lakes in the area. But when I was a child, most of the small lakes were dry," the civil and environmental engineering professor said during a recent break in Davis Hall, where she's setting up her new lab. "I did feel that the environment continuously deteriorated with time as I grew up."

That experience piqued Mi's interest in water and the environment—a journey that has led her from the small town of Zhengding in northeastern Hebei province to—most recently—Berkeley's campus, where she is pioneering research in new ways to purify water and wastewater.

Mi, who joined the college faculty last summer, is developing a new type of membrane that could outperform today's water filtration technology and consume less energy in the process. Her design is constructed from graphene oxide, a carbon-based material that's made from naturally-occurring graphite, the same material found in pencils.

Graphene or graphene oxide is often heralded by scientists as having particular promise for use in a range of environmental-related applications, including energy storage, hydrogen fuel production and removing air pollution. Made from a thin layer of carbon, the material is lightweight yet strong, and can conduct heat and electricity very well. It's also abundant and inexpensive.

Mi says that membranes made from graphene or graphene oxide can more effectively remove wastewater contaminants—including pharmaceuticals, pathogens and endocrine disruptors—than current methods and can be applied to wastewater reuse, water desalinization and storm water treatment.

In the past, scientists attempted to make desalination membranes using graphitic oxide. But those forays failed, Mi says, because of the material's structure and size. "Graphitic oxide is a large particle containing numerous layers of carbon, so the resulting membrane is thick, with a very low water filtration rate." she says.

In contrast, graphene and graphene oxide are two-dimensional materials, and the 2-D structure enables scientists to stack sheets of graphene oxide together to make very thin membranes. Water can flow extremely fast between stacked sheets of graphene, Mi adds, because there's little friction from its structure. Adding oxygen to graphene turns it into graphene oxide and opens up more space in the structure for water to flow through, she says.

The longstanding problem with graphene oxide membranes has been that adding oxygen makes graphene more likely to dissolve in water.

But when Mi was able to adhere a chemical to the sheets of graphene oxide to "glue" them together, the membrane stayed intact in water. The results of that breakthrough were published in a 2013 academic journal.

Developing a new application for graphene oxide is a culmination of Mi's almost single-minded focus on how water-filtering membranes work—a quest that started over 15 years ago during her senior year of college at Tianjin University. During that year, she was exposed to membrane filtration systems for the first time while conducting lab research with a professor.

As a doctoral student at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign, she capped off her student career with a dissertation on using membranes for arsenic removal. Then, after a post-doc at Yale (where she focused on forward osmosis) and taking on a faculty position at George Washington University, she arrived at the University of Maryland, where she first started her research on graphene oxide.

Mi—who taught a course at Berkeley last semester on emerging technology for water sustainability—was granted a patent on the membranes in 2015. And though companies have expressed interest in commercializing the technology, she says it needs to be tested at a larger scale first.

Still, Mi says she believes that the membrane would be very attractive to government and industry, especially in the midst of California's longstanding drought. That's because their ability to be more energy-efficient and less costly makes them potentially useful in seawater desalination—an approach that has been raised as a potential solution to increase the state's water supply, yet is considered today to be largely infeasible due to the high costs and energy intensive needs of desalination plants.

Mi adds that there's another practical advantage to using graphene oxide membranes: Because they function with a physical separation process, they can be scaled up to large treatment plants or down to a household level, hooked up to a tap.

"It's very flexible, compact and low maintenance," she says. "We're working really hard right now to make them work for desalination."

Provided by University of California - Berkeley