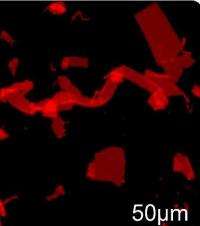

Fluorescence microscope image of nanosheets (some overlapped and folded) formed by manually shaking a vial, labeled with Nile Red dye and depositing solution on an agarose substrate. (Zuckerman, et. al)

(PhysOrg.com) -- Stir this clear liquid in a glass vial and nothing happens. Shake this liquid, and free-floating sheets of protein-like structures emerge, ready to detect molecules or catalyze a reaction. This isn’t the latest gadget from James Bond’s arsenal -- rather, the latest research from the DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) scientists unveiling how slim sheets of protein-like structures self-assemble. This "shaken, not stirred" mechanism provides a way to scale up production of these two-dimensional nanosheets for a wide range of applications, such as platforms for sensing, filtration and templating growth of other nanostructures.

“Our findings tell us how to engineer two-dimensional, biomimetic materials with atomic precision in water,” said Ron Zuckermann, Director of the Biological Nanostructures Facility at the Molecular Foundry, a DOE nanoscience user facility at Berkeley Lab. “What’s more, we can produce these materials for specific applications, such as a platform for sensing molecules or a membrane for filtration.”

Zuckermann, who is also a senior scientist at Berkeley Lab, is a pioneer in the development of peptoids, synthetic polymers that behave like naturally occurring proteins without degrading. His group previously discovered peptoids capable of self-assembling into nanoscale ropes, sheets and jaws, accelerating mineral growth and serving as a platform for detecting misfolded proteins.

In this latest study, the team employed a Langmuir-Blodgett trough – a bath of water with Teflon-coated paddles at either end – to study how peptoid nanosheets assemble at the surface of the bath, called the air-water interface. By compressing a single layer of peptoid molecules on the surface of water with these paddles, said Babak Sanii, a post-doctoral researcher working with Zuckermann, “we can squeeze this layer to a critical pressure and watch it collapse into a sheet.”

“Knowing the mechanism of sheet formation gives us a set of design rules for making these nanomaterials on a much larger scale,” added Sanii.

To study how shaking affected sheet formation, the team developed a new device called the SheetRocker to gently rock a vial of peptoids from upright to horizontal and back again. This carefully controlled motion allowed the team to precisely control the process of compression on the air-water interface.

“During shaking, the monolayer of peptoids essentially compresses, pushing chains of peptoids together and squeezing them out into a nanosheet. The air-water interface essentially acts as a catalyst for producing nanosheets in 95% yield,” added Zuckermann. “What’s more, this process may be general for a wide variety of two-dimensional nanomaterials.”

This research is reported in a paper titled, “Shaken, not stirred: Collapsing a peptoid monolayer to produce free-floating, stable nanosheets,” appearing in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS) and available in JACS online. Co-authoring the paper with Zuckermann and Sanii were Romas Kudirka, Andrew Cho, Neeraja Venkateswaran, Gloria Olivier, Alexander Olson, Helen Tran, Marika Harada and Li Tan.

Provided by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory