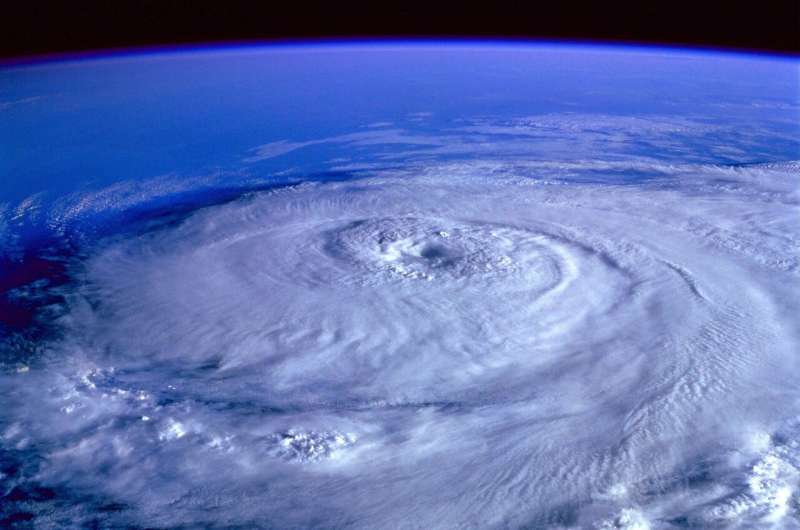

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Hurricanes Michael, Dorian, Ian, Nicole and Idalia have all been stared down by one of the NOAA's most powerful satellites since it took its place in geostationary orbit in late 2017. Its replacement is gearing up for launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy later this month.

The GOES-U satellite is the 19th Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite in the NOAA and NASA partnership since the first one launched in 1975. It's the fourth and final of the latest version of the satellites. The first three are already parked at more than 22,000 miles altitude and have their wide-view sites set to track tropical weather, fires, lightning and other dangerous weather on Earth.

The final satellite sits in a stark, white clean room at Astrotech Space Operations' payload processing facility just across the river from Kennedy Space Center. It's already fueled and awaits encapsulation in a SpaceX fairing before heading to KSC for launch. Liftoff is slated for June 25 at 5:16 p.m. during a two-hour window atop what will be the first Falcon Heavy launch of the year.

All four satellites are part of what NOAA calls the GOES-R series, the most powerful satellites for weather forecasting.

GOES-R launched in 2016 and took over the role of watching the Atlantic basin once it was in position a year later. Sister satellites GOES-S launched in 2018 and GOES-T in 2022, setting up the final GOES-U launch this year.

"The GOES-R series has about 60 times more data delivered than the previous generation," said the NOAA satellites' program director Pam Sullivan, touting its primary tool, the Advanced Baseline Imager, "that is able to take pictures of phenomena as often as every 30 seconds."

She said it brought real-time forecasting and "put that in the hands of your local forecaster to tell you exactly what's going on in your neighborhood at that time."

That includes having an operational lightning mapper for the first time in geostationary orbit, taking pictures 500 times a second.

"That's how fast you have to take it when you're trying to watch lightning," she said. "That data is getting down to people. It can tell them when thunderstorms are intensifying. It can tell them things about strengthening of hurricanes, and it can also help track when wildfires are started by lightning."

Dan Lindsey, GOES-R program chief scientist, said the National Weather Service and National Hurricane Center rely on weather models as their primary forecasting tool, and that's where the satellites come in. They give the best data for "what's happening right now everywhere."

"They tell you where the clouds are, they tell you what the temperature and water vapor distribution in the atmosphere is. Then they tell you what the winds are doing, how strong are the winds that are in the jet stream, things like that," he said. "That's really critical to know what's happening now in order to forecast what's going to happen tomorrow."

The NOAA estimates the total cost to build, launch and maintain the four satellites in this series is between $7 billion and $8 billion over their lifespan, estimated at 10 to 20 years.

"They will live for a long time, and they will be helping people really into the late 2030s," said Sullivan.

Once it makes it to space, each satellite earns a name change in the form of a number. The GOES-R became GOES-16. NOAA has assigned it the duties of watching the eastern hemisphere including the Atlantic and Caribbean, which it began in late 2017 ahead of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season. So it's also known as GOES-East.

There's also a GOES-West parked in space looking at the Pacific and a spare GOES satellite in case one of the two were to malfunction.

With the launch of GOES-U, though, it will become GOES-19, and make its way to take over the GOES-East duties by April 2025.

For the most part, all four offer the same suite of instruments. The satellite bus is built by Lockheed Martin while the primary tool is the Advanced Baseline Imager built by Melbourne-based L3Harris Technologies.

"You can think of it as camera that takes pictures in 16 different spectral bands, or colors, across visible—what you can see with your eyes—as well as infrared," said Daniel Gall, a payload architect with L3Harris. "We use that to image clouds and severe weather, track hurricanes, track severe storms. So basically anytime you open up an app on your phone, you're seeing images, those are coming from our Advanced Baseline Imager."

One new item, though, on the GOES-U satellite is an instrument called a compact coronagraph to look at the sun. Attached to the solar arrays, it will look away from the Earth to image the outer layer of the sun's atmosphere specifically targeting coronal mass ejections such as those that bombarded Earth with geomagnetic storms and brought the aurora borealis farther in May.

Jim Spann, senior scientist for space weather in the NOAA's office of Space Weather Observations, said it will be the first operational tool to keep track of the phenomenon, which is right now mostly seen by the nearly 30-year-old Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO).

"It's way past its lifetime," he said while also noting SOHO suffers from gaps of up to eight hours during which it cannot see the sun. "We can observe the outer corona of the sun 24/7."

Knowing when bad geomagnetic storms are coming lets the NOAA give everyone the heads-up needed to manage the disruption.

"The impact of those, that's when we would really have a bad day," he said. "Where not only would it impact communications, but it also would induce currents on power lines and could take out large segments of the whole northeast if a really bad one were to happen."

NOAA is counting on these satellites to last until the new series called Geostationary Extended Observations (GeoXO) is built. Contracts on those are in the process of being awarded, but those won't be launching until at least 2032. Their lifespan, though, will extend into the 2050s.

"This is going to take us past many of our retirements and into the future and into our kids' generations," Lindsey said.

2024 Orlando Sentinel. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.