Artist’s concept of a Dyson sphere. Credit: SentientDevelopments.com

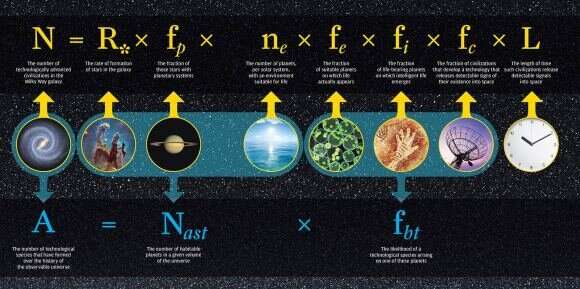

The Drake equation is one of the most famous equations in astronomy. It has been endlessly debated since it was first posited in 1961 by Frank Drake, but so far has served as an effective baseline for discussion about how much life might be spread throughout the galaxy. However, all equations can be improved, and a team of astrobiologists and astronomers think they have found a way to improve this one.

The equation itself was centered around the search for radio signals. However, its formulation would imply that it is more likely to see what are now commonly called "biosignatures" rather than technological ones. For example, astronomers could find methane in a planet's atmosphere, which is a clear sign of life, even if that planet hasn't developed any advanced intelligence yet.

That search for biosignatures wasn't possible when Drake originally wrote the equation—but it is now. As such, it might be time to modify some of the factors in the original equation to reflect scientists' new search capabilities better. One way to do that is to split the equation into two separate ones, reflecting the search for biosignatures and technosignatures respectively.

Biosignatures, captured in the new framework by the term N(bio), would likely develop much more commonly than technosignatures, captured in the new framework as N(tech). Logically that would result from the fact that the number of planets that go on to develop a technologically advanced civilization is much less than the total number of planets that form life in the first place. After all, it took Earth around 4 billion years after its first spark of life to develop an intelligent civilization.

Graphical depiction of a modified Drake equation, and each of its constituent components. Credit: University of Rochester

But that doesn't account for a fundamental characteristic of technology—while it might have to originate from a planet with a biosphere, it certainly doesn't have to stay there. This significantly impacts another factor in the Drake equation—L or the length of time that a signal is detectable. Dr. Jason Wright of Penn State University, the first author of the new paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and his co-authors point out that four factors point to technology being potentially longer-lived than biology.

First, as would be apparent to anyone who is a fan of science fiction, technology can long outlive the biology that created it. In fact, in some cases, the technology itself can destroy the biosphere that created it. But it would still be detectable, even at a distance, long after the lifeforms that had created it had died off. And it could do so on the order of millions or even billions of years, depending on the robustness of the technology.

If the lifeforms didn't die off in the early stages of their technological awakening, they probably would want to expand to other planets and would take their technology with them. Which leads to the second factor—technospheres can potentially outnumber biospheres. For example, if lunar colonization moves steadily over the next few hundred years, the moon would become a world with no biosphere but would very clearly have a technosphere around it.

UT video discussing the fate of intelligent civilizations.

Moving even further up the technology tree, technology itself could become self-replicating, such as a von Neumann probe or another self-replicating system. These would be able to leave any originating biosphere behind, but they could also potentially keep going long after whatever biology had initially created them had moved on.

That would hint at the fourth factor—that technosignatures can even exist without a planet at all, in the form of spacecraft or satellites. In fact, this might even be the most common form of technosignature in the galaxy. As such, the limiting factors of the Drake equation, which are all directly tied to a planet, don't apply to technology.

One other factor affects how easy it would be to find biosignatures versus technosignatures—how detectable they are. Dr. Wright and his colleagues mention that biosignature detection is challenging—in fact, we currently can't even detect Earth's biosignature at the distance of Alpha Centauri. Data from James Webb might eventually allow for that. But even so, radio astronomy projects such as the Square Kilometer Array are much more attuned to detecting what are clearly signs of technology.

UT video on searching for biosignatures

Just how clearly is another sticking point, though, for both biosignature and technosignature searchers. For both categories, it can be challenging to separate a valid signal from the "noise," which can take many forms, such as muddied spectral analysis or heat signatures. Despite that, Dr. Wright and his team make a strong case that technosignatures at least have the potential to be much clearer than any biosignatures, which are likely unintentional side effects of the growth of life more generally.

What all this means is simple—the search for extraterrestrial intelligence should continue, and it is probably more likely to find a sign of a technologically advanced civilization than it is to find a burgeoning non-technological one. Even if the civilization that created the signal is long gone, that would still hold true. That permanence can be viewed as either a somber side effect or the happy result of years of evolution and discovery. You can decide for yourself which way to look at it.

More information: Jason T. Wright et al, The Case for Technosignatures: Why They May Be Abundant, Long-lived, Highly Detectable, and Unambiguous, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2022). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac5824

Journal information: Astrophysical Journal Letters

Provided by Universe Today