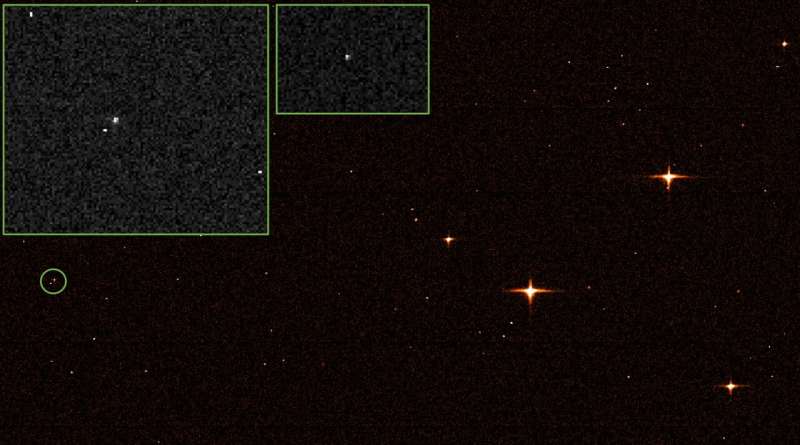

Gaia’s sky mapper image showing the James Webb Space Telescope. The reddish colour is artificial, chosen just for illustrative reasons. The frame shows a few relatively bright stars, several faint stars, a few disturbances – and a spacecraft. It is marked by the green arrow. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Both spacecraft are located in orbits around the Lagrange point 2 (L2), 1.5 million km from Earth in the direction away from the Sun. Gaia arrived there in 2014, and Webb in January 2022.

On 18 February 2022, the two spacecraft were 1 million km apart, with an edge-on view of Gaia towards Webb's huge sunshield. Very little reflected sunlight came Gaia's way, and Webb therefore appears as a tiny, faint spec of light in Gaia's two telescopes without any details visible.

Sky mapper

A few weeks before Webb's arrival at L2, Gaia experts Uli Bastian of Heidelberg University (Germany) and Francois Mignard of Nice Observatory (France) realized that during Gaia's continuous scanning of the entire sky, its new neighbor at L2 should occasionally cross Gaia's fields of view.

Gaia is not designed to take real pictures of celestial objects. Instead, it collects very precise measurements of their positions, motions, distances, and colors. However, one part of the instruments on board takes a sort of sky images. It is the "finder scope" of Gaia, also called the sky mapper.

Gaia orbits the second Lagrange Point (L2) in a Lissajous orbit. The James Webb Space Telescope orbits L2 in a halo orbit. The telescopes are between 400 000 and 1 100 000 km apart, depending on where they are in their respective orbits. This image shows the relative sizes and locations of the Gaia orbit (yellow) and the Webb orbit (white). In this view Earth is located to the left, not far outside of the frame. Gaia’s Lissajous loops have L2 right in their centre, while Webb’s halo orbit loops are closer to Earth by about 100 000 km on average. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Every six hours, Gaia's sky mapper scans a narrow 360-degree strip around the entire celestial sphere. The successive strips are slightly tilted with respect to each other, so that every few months the entire sky is covered—touching everything that's there and that's bright enough to be seen by Gaia. Within seconds, these slices are automatically scrutinized for star images, the positions of which are then used to predict when and where those stars could be recorded in Gaia's main scientific instruments. Then they are routinely deleted.

But the computer can be manually requested to exceptionally keep a stretch of the image data. The sky mapper was originally planned for technical servicing purposes, but during the mission it has also found some scientific uses. Why not use it for a snapshot of Webb?

Background frame: Cutout of the specially recorded image from Gaia’s sky mapper instrument at the first of the two observations from Gaia’s two telescopes. The reddish colour is artificial, chosen just for illustrative reasons. The frame shows a few relatively bright stars, several faint stars, a few disturbances – and a spacecraft. It is marked by the green circle. Left grey inset: Zoom into the frame showing the Webb image at full resolution. It is the slightly extended speck of light in the centre. The other three bright dots are traces of energetic cosmic-ray particles which hit the CCD chip during the 2.5 seconds of exposure. The on-board software is capable of autonomously and reliably distinguishing these from star images. Right grey inset: The second “photo” of Webb, taken in the second field of view of Gaia’s telescopes about 106.5 minutes after the first one. Each of the two images were created by just under 1000 sunlight photons arriving from the Webb spacecraft. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Got it!

After Webb had reached its destination at L2, the Gaia scientists calculated when the first opportunity would arise for Gaia to spot Webb, which turned out to be 18 February 2022.

After Gaia's two telescopes had scanned the part of the sky where Webb would be visible, the raw data was downloaded to Earth. In the morning after, Francois sent an email to all people involved. The enthusiastic subject line of the email was "JWST: Got it!!"

On 18 February, the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope was photographed by ESA’s Gaia observatory. Both spacecraft are located at Lagrange point 2 (L2), 1.5 million km from Earth in the direction away from the Sun. Gaia arrived there in 2014, and Webb in January 2022. Gaia orbits L2 in a Lissajous orbit. The James Webb Space Telescopes orbits L2 in a halo orbit. On 18 February 2022, the two spacecraft were 1 million km apart, with an edge-on view of Gaia towards Webb’s huge sunshield. Very little reflected sunlight came Gaia’s way, and Webb therefore appears as a tiny, faint spec of light in Gaia’s two telescopes without any details visible. This animation was created with Gaia Sky. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC

The astronomers had to wait a few more days for Juanma Martin-Fleitas, ESA's Gaia calibration engineer, to identify Webb in the sky mapper images. "I've identified our target" was the message sent by him, with the images attached and the two tiny specks labeled as "Webb candidates."

After scrutinizing these carefully, Uli replied: "Your 'candidates' can be safely renamed 'Webb.'"

Gaia now has a spacecraft friend at L2, and together they will uncover our home galaxy, and the universe beyond.

Provided by European Space Agency