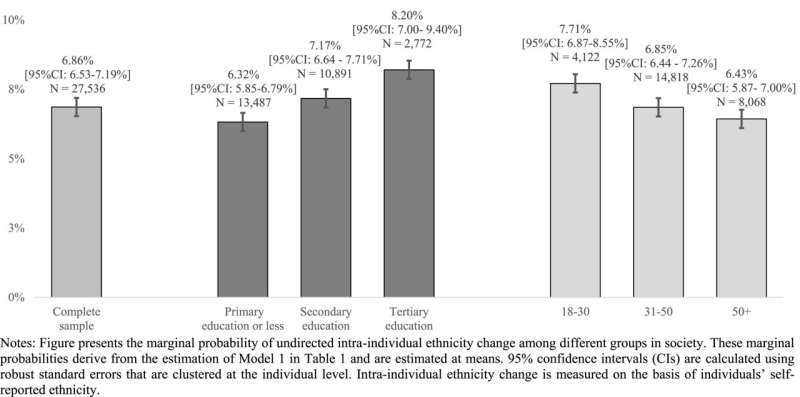

Fig. 1. Marginal probability of intra-individual ethnicity change among different age cohorts and educational groups. Credit: DOI: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102694

Ethnicity often plays a prominent role in debates at every level of Dutch society. But what exactly is ethnicity, and is it as set in stone as we believe? Research conducted by Radboud University's Robbert Rademakers and André van Hoorn has shown that, during their lifetime, millions of people across the world will assume a different ethnicity. Their research will now be featured in the Journal of Development Economics. "Ethnicity is not a fixed biological fact, but a concept that is interpreted differently by everyone."

The study shows that ethnicity is not nearly as unmalleable as has long been thought. For their research, Rademakers and Van Hoorn used datasets from millions of Indonesian, Indian and the American inhabitants. These people were asked about their ethnicity at various points in their lives. Seven percent of the Indonesians from the dataset self-reported different ethnicities during the measurement period, while the percentage in the US was slightly lower.

Debate

This is significant because ethnic background is not only frequently used in scientific studies, but it is also used in public debate to indicate trends in society. "Government agencies, for example, collect data on income, education and health and ask survey participants to state their own ethnicity. But if people suddenly start to identify with a different ethnicity during the course of their lives, this will have an impact on the way in which we need to interpret this data," explains Rademakers.

Ethnicity is interpreted in different ways by people from different countries. Rademakers: "It's a feeling of shared ancestry, a common past. The way in which ethnicity is expressed differs from country to country. In America, ethnicity is primarily about skin color, while in other countries it may be about language, nationality, region of birth, and so on."

Interethnic marriage

The article mentions various reasons for the change in ethnicity: for instance, people may adopt the ethnicity of their partner after they get married, or adopt a different ethnicity when they move to another region. Rademakers: "Consider a second or third generation Chinese-American woman who marries a white person. This person may become increasingly distant from the identity that derives from their original ethnicity, and at some point they may subsequently identify as white. This, in turn, will affect the figures for interethnic marriages. Officially speaking, the percentage of interethnic marriages in the United States is only 5 percent, but if you look at the actual figures, the percentage is closer to 10 percent."

Although the researchers did not have access to Dutch datasets, they expect that other assumptions about ethnicity will need to be made here as well. André van Hoorn: "If someone's grandparents or great-grandparents came from Turkey, we still refer to them as a Turkish Dutchman, but that doesn't say anything about the extent to which this person has integrated into Dutch society. It's vital that we continue to question the information content of the data on ethnicity: it may be able to provide insight into discrimination in the job market, for example, but we shouldn't use it too rigidly. If we fail to understand that ethnic identity is fluid, it will create a massive blind spot in the way in which we perceive society."

More information: Robbert Rademakers et al, Ethnic switching: Longitudinal evidence on prevalence, correlates, and implications for measuring ethnic segregation, Journal of Development Economics (2021). DOI: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102694

Provided by Radboud University