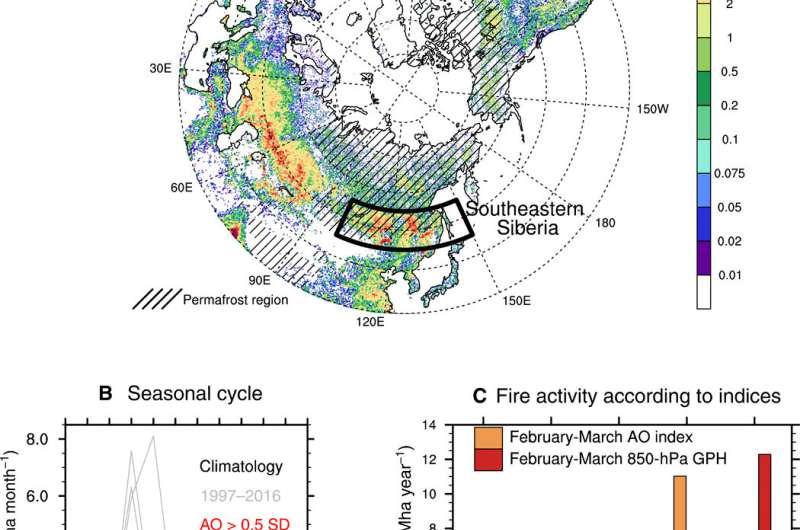

Fire activity over southeastern Siberia. (A) Mean burned area fraction (% year−1) over mid- and high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. Hatched areas indicate permafrost regions. The black box indicates the study area in southeastern Siberia (100°–150°E, 45°–55°N). (B) Monthly burned area (Mha month−1) in southeastern Siberia for 1997–2016 in each year (gray), mean (thick black), composite for February to March AO index > 0.5 SD cases (red), and AO < −0.5 SD cases (blue). (C) Mean burned area according to February to March AO index (orange) and 850-hPa geopotential height anomaly over southeastern Siberia (red). Bins on the x axis indicate <20%, <40%, <60%, <80%, and <100% rank ranges. Credit: Science Advances (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aax3308

A team of researchers from the U.K., South Korea and Japan has found evidence that in positive phase years, the Arctic Oscillation can boost late winter temperatures in Siberia, resulting in more forest fires in the spring. In their paper published in the journal Science Advances, the group describes studying a 20-year global weather period and their findings.

As the planet continues to heat due to human activities, some parts of the world will naturally add more CO2 to the atmosphere. The Arctic regions are one such place. As temperatures rise, permafrost melts, releasing stored CO2—this has led to faster rising temperatures in the Arctic region than other parts of the planet. In this new effort, the researchers have found that global warming may also be leading to another rising source of CO2—burning trees.

Prior research has shown that due to opposing patterns of air pressure in the middle latitudes and the Arctic, air circulation patterns emerge in the northern hemisphere. These patterns, known as the Arctic Oscillation, can have a dramatic impact on weather in the areas below them. During what is known as its positive phase, air pressure in the Arctic drops below that over the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, pulling warm air masses north in some parts of the northern hemisphere and pushing some south. Air masses are pushed north in Siberia, resulting in warmer late winters. And warmer late winters mean earlier snowmelt. And that earlier snowmelt, the researchers have found, can lead to an increase in forest fires. To learn more about the impact of the Arctic Oscillation on weather patterns, the researchers studied weather and fire statistics in Siberia from information in global databases over the years 1997 to 2016. They found a pattern—when there was a positive phase in later winter, there tended to be an increase in forest fires in Siberia in the spring.

In addition to endangering lives and property in Siberia, an increase in forest fires means more of the CO2 sequestered in trees is released into the atmosphere, adding to the amount that is already there and contributing to climate change.

The findings indicate that if weather forecasters in Siberia keep tabs on the Arctic Oscillation, they can warn residents of an impending early snow melt and a subsequent increase in forest fires—this would allow the population to take proactive action to protect themselves.

More information: Jin-Soo Kim et al. Extensive fires in southeastern Siberian permafrost linked to preceding Arctic Oscillation, Science Advances (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aax3308

Journal information: Science Advances

© 2020 Science X Network