A farmer in the Szechuan Province of China tends to his remaining crops after returning a portion of his cropland to be reforested. Credit: Hongbo Yang, Michigan State University

Returning croplands to forests is a sustainability gold standard to mitigate climate change impacts and promote conservation. That is, new research shows, unless you're a poor farmer.

"Those sweeping conservation efforts in returning cropland to vegetated land might have done so with an until-now hidden consequence: it increased the wildlife damage to remaining cropland and thus caused unintended cost that whittled away at the program's compensation for farmers," said Hongbo Yang, lead author in a recent paper in the Ecological Economics journal.

Yang, who recently earned a Ph.D. at from Michigan State University (MSU) and is currently a research associate at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and his colleagues analyzed the reforestation achieved via programs that encourage, and compensate, farmers to convert their cropland to forests via China's enormous Grain-to-Green Program (GTGP).

The research found that even as newly regrown forests are sucking up greenhouse gases, they're also sheltering critters bent on destroying crops. And while farmers were compensated, they ultimately took a financial beating. Not only did they find that converting a portion of their fields brought wildlife that much closer to their remaining crops, but they were also now farming smaller areas and thus recognizing lower yields.

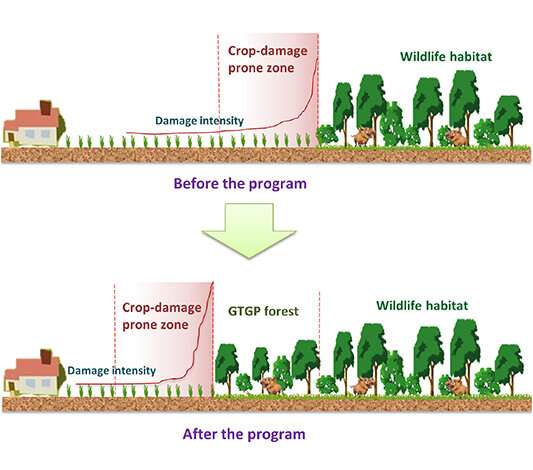

Illustration of the change of crop damage by wildlife before and after afforestation on cropland promoted by conservation program. Before afforestation, cropland close to wildlife habitat is more severely affected by crop damage by wildlife than distant ones. After afforestation, cropland close to wildlife habitat are afforested and the nearby remaining cropland becomes more severely affected by crop damage by wildlife. Credit: Michigan State University

Bottom line: The costs of conservation were being borne by poor people and those impacts have been slow to be revealed.

"Conservation policies only can endure, and be declared successful, when both nature and humans thrive," said Jianguo "Jack" Liu, senior author and Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability at MSU'S Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability. "Many of these trade-offs and inequities are difficult to spot unless you take a very broad, deep look at the situation, yet these balances are crucial to success."

As a first attempt to quantify this previously hidden cost, the authors estimated the impact of converting cropland to forest under the GTGP, which is one of the world's largest conservation programs, on crop raiding in a demonstration site.

They found that GTGP afforestation was responsible for 64% of the crop damage by wildlife on remaining cropland, and that cost was worth 27% of GTGP's total payment to local farmers. That loss was not anticipated as the policy was designed and was in addition to the known loss of income from farming smaller plots, Yang said.

"The ignorance of this hidden cost might leave local communities under-compensated under the program and exacerbate poverty," Yang said. "Such problems may ultimately compromise the sustainability of conservation. As losses due to human-wildlife conflicts increase, farmers may increasingly resent conservation efforts."

More information: Hongbo Yang et al, Hidden cost of conservation: A demonstration using losses from human-wildlife conflicts under a payments for ecosystem services program, Ecological Economics (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106462

Provided by Michigan State University