The UK's efforts to boost productivity while ironing out regional inequalities in job creation may be fundamentally at odds, according to a joint study of so-called 'gazelle' firms by Aston University and the London School of Economics.

The findings, based on a study of 6.25m firms over a 17-year period by the Enterprise Research Centre (ERC), shed new light on the 'spillover effects' high-growth firms have on other businesses in their region.

In recent years, policymakers have looked to high-growth firms – dubbed 'gazelles' – as a way of tackling the UK's chronic productivity problem. Despite accounting for less than 5 percent of businesses, these companies create around half of all new jobs and typically show higher levels of productivity.

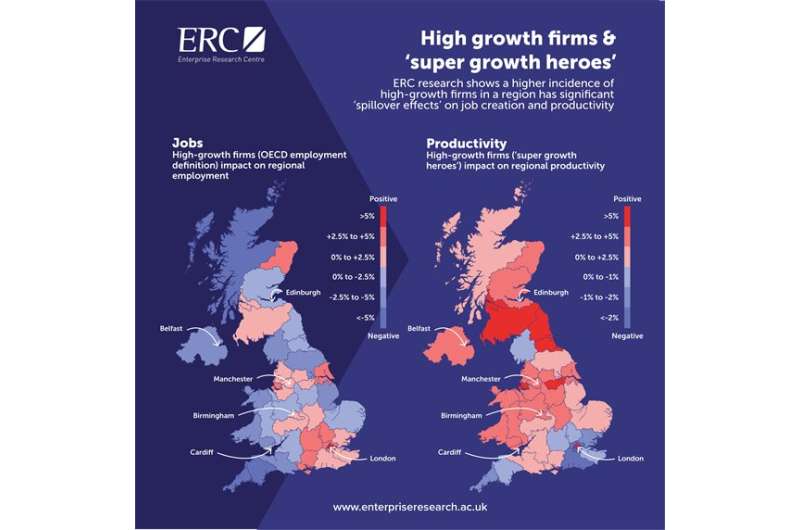

But the research shows that high-growth firms should actually be broken down into two distinct camps – a 'traditional' group with fast employment growth (20 percent growth per year over three years, as defined by the OECD) and a separate group of 'super growth heroes' that boost their productivity by growing turnover faster than headcount.

The fast-employment group – spread relatively evenly across the country—was found to hoover up jobs from slower-growing firms in the same region, in what the researchers call a "crowding-out competition effect".

The study by Professor Jun Du of Aston University and Dr. Enrico Vanino of the London School of Economics tracked the experiences of 6.25m firms over a 17-year period. The researchers focused their attention on the 1m manufacturing and professional services firms that experienced an episode of fast growth.

Professor Jun Du said:

"This research shows that the policy goals of job creation and productivity growth are not always complementary at the regional and sector level.

"With the government's industrial strategy seeking to rebalance the UK economy, policymakers nationally and locally need to be mindful that while encouraging clusters of fast-growth firms can bring productivity benefits to whole supply chains, some regions and industries with acute skills shortages could see unintended consequences.

"We see this particularly in parts of Britain that are distant from major urban centres, with a hollowing-out effect when it comes to net job creation, underlining the need for place-based growth strategies that take account of local circumstances."

The ERC has also published new research highlighting how high-growth episodes in cohorts of firms of similar age is more important than counting the number of high-growth firms (HGFs) in arbitrary three-year periods – the standard definition used by the OECD.

A key finding from following a cohort of firm start-ups from 1998 to 2013 is that the likelihood of an HGF having a further episode of high-growth declines steeply as time elapses. Over the long term, these firms often see their annual average growth rates reduce to the level of firms never classed as HGFs.

Lead researcher and ERC Deputy Director, Professor Mark Hart, said:

"Policymakers need to be careful not to over-focus on trying to 'create' more HGFs, but on learning from their experiences of episodic growth over longer time periods to understand firm growth better."

Provided by Aston University