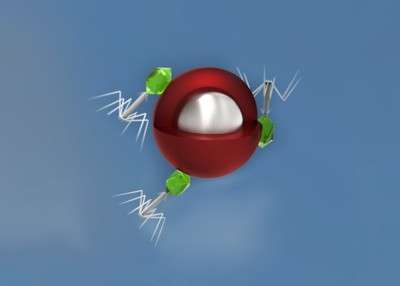

Bioconjugate is a complex formed by the combination of a microparticle (here represented as a red-white sphere) with biomolecules (T4 bacteriophages were used in experiments in IPC PAS). Credit: IPC PAS

Soon, hospitals will be able to identify the bacterial species responsible for a patient's developing infection in a matter of just a few minutes. A new, easy-to-adapt and inexpensive analytical procedure has been developed by researchers from the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. The main role is played by innovative bioconjugates—luminescent, magnetic microparticles coated with appropriately selected bacteriophages.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with advanced bacterial infection like sepsis, time is crucial. The sooner it is possible to diagnose infection, the greater the chance of successful treatment. Meanwhile, commonly used analytical methods still require the multiplication of bacteria (which often takes several days) or specialized equipment available in only a few laboratories. The identification of bacteria can now be carried out in almost any hospital analysis laboratory in a matter of minutes, according to a study by the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IPC PAS) in the respected scientific journal Bioconjugate Chemistry.

Before developing the new analytical technique, researchers from the IPC PAS assumed that it should allow for significantly faster identification of bacteria than existing methods and be easy to introduce in a large number of hospital laboratories with high measurement accuracy. Additionally, the analysis should be inexpensive.

"Faster, better, cheaper—we managed to achieve all of these objectives," says Dr. Jan Paczesny (IPC PAS), who led the research project, adding that the team has opted not to patent their discovery.

The detection device in the new technique for identifying bacteria is a flow cytometer. It is quite a simple and relatively inexpensive piece of equipment commonly used for blood tests in many hospitals. In the cytometer, the sample is passed through a nozzle in a stream so narrow that all the larger particles in the solution, particularly cells, are forced to flow one by one. The stream is lit by lasers and surrounded by detectors that record the light reflected from individual particles, scattered to the sides, and emitted by them.

The main problem was developing a method for labelling the bacteria for easy interception in the test sample and identifying them with great certainty via the cytometer. To do this, researchers constructed special bioconjugates, i.e. complexes formed by the combination of microparticles with biomolecules. The biological element was a bacteriophage, which is a virus infecting a particular species of bacteria—the IPC PAS experimenters used the T4 bacteriophage, attacking Escherichia coli bacteria. The bacteriophages were coupled with microparticles capable of emitting light that could be easily registered on the cytometer and which exhibited magnetic properties. This was essential, because it made it possible to separate the bioconjugates from other particles in the sample with a simple magnet.

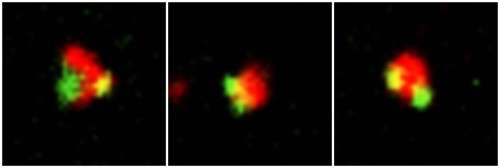

These are images obtained with confocal microscopy show magnetic microparticles (red) with two or three bacteriophages (green). Credit: IPC PAS

"We started by searching for inexpensive, commercially available microparticles that met our requirements. It turned out that appropriate particles were already available on the market—and exactly the ones we were looking for! Their surface was covered with just those chemical functional groups we needed to place virtually any type of bacteriophage on them," explains Ph.D. student Marta Janczuk-Richter from the group of Prof. Joanna Niedziolka-Jonsson.

The researchers combined the purchased microspheres with bacteriophages using a compound from the carbodiimide group known as EDC (this substance is used by many chemists to bind together different particles). Images obtained with confocal microscopy confirmed that in the new bioconjugates usually two or three bacteriophages adhered to each microparticle. Therefore, the world's first bioconjugates with triple functions were obtained: binding only to one species of bacteria, responsive to the magnetic field and capable of glowing (fluorescent).

The procedure for identifying bacteria using such constructed bioconjugates is simple. The sample, such as a physiological fluid obtained from the patient, is diluted; then a small amount of previously prepared bioconjugates is added to the solution. It takes a short while for the bioconjugates to attach to the bacteria. Next, a magnet is applied to the sample and all bioconjugates are attracted, including those with the attached bacteria. After pouring out the remainder of the sample and re-dilution of the separated precipitate, the solution is passed through the cytometer.

Bioconjugates can help to identify the bacterial species in hospitals in a matter of just a few minutes. Credit: IPC PAS, Grzegorz Krzyzewski

"Measurement in the cytometer typically takes about a minute. The result is a graph on which we see how all the bioconjugates scatter the incident light and emit fluorescence. Since we know the signal we should obtain from pure bioconjugates without bacteria, we can easily determine whether the sample contains the bacteria we are looking for, and if so, in what concentration," says PhD student Łukasz Richter from the group of Prof. Robert Holyst.

Tests at the IPC PAS have shown that usually several bioconjugates attach to each bacteria. Theoretically, it would thus be possible to detect even a single bacterium. In practice, however, certain limitations arise from the properties of the microparticles and the characteristics of the measuring apparatus. Pure bioconjugates may, in fact, clump together into larger clusters that generate a signal in the cytometer similar to single bioconjugates with attached bacteria.

Bioconjugates with one type of bacteriophage detect only one species of bacteria. However, due to the ease of preparation of bioconjugates, interested hospital laboratories could prepare a dozen or even several dozen types of potentially useful bioconjugates without difficulty, each of them with bacteriophages infecting different species of bacteria. In the case of sepsis, which is caused in most cases by only over a dozen species of bacteria, carrying out the identification would then require the simultaneous performance of at most a dozen tests. The entire procedure should take no more than an hour, the researchers say.

More information: Marta Janczuk et al, Bacteriophage-Based Bioconjugates as a Flow Cytometry Probe for Fast Bacteria Detection, Bioconjugate Chemistry (2016). DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00596

Journal information: Bioconjugate Chemistry

Provided by Polish Academy of Sciences