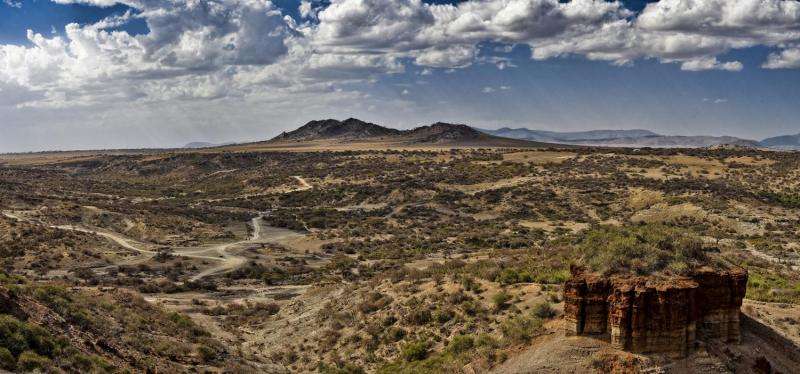

Olduvai Gorge. Credit: Wikipedia

Because most of the evidence of early humans derives from the fossil record, it is difficult to discern a great deal about their lifestyles and habits. Scientists can make inferences from skeletal morphology—jaw and teeth fossils can provide evidence of likely dietary habits, for instance. The influence of local resources on ancestral humans is therefore difficult to determine.

However, geologic studies can reveal a wealth of information about ancient localities that opens a new dialogue about dietary resources, refuge and habits. A collaborative of researchers from Rutgers University, Complutense University in Spain, and Pennsylvania State University have published the results of a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in which they analyzed exceptionally well preserved, 2 million-year-old organic geochemical biomarkers from different plant communities at Olduvai Gorge.

Meet Paranthropus boisei

Paranthropus bosei was an early hominid that occupied Eastern Africa from 2.3 million to 1.2 million years ago. P. bosei was discovered in 1959 by Mary Leakey in the Olduvai gorge. Leakey and her son Richard suggested that it might be the earliest hominid to fashion stone tools.

P. boisei had a small brain and a jaw configuration adapted for powerful chewing, with large molars and the thickest enamel of any known hominin. Truly, the fossilized jaws uncovered by anthropologists have molars that are visibly immense compared with modern humans.

Like other ancestral hominins, P. boisei's morphologic features have been well documented, but until the current study, no direct evidence of its local resources existed from which inferences could be drawn. The researchers analyzed freeze-dried and powdered paleosol samples from across an archaeological horizon at Olduvai Gorge. Plant biomarkers in soil can distinguish plant functional type differences in standing biomass, and this information suggests a number of resources that would have been available fo P. boisei around 2 million years ago.

P. boisei's notable teeth have isotopic properties indicating that the species was water dependent and ate large quantities of abrasive, carbon-enriched foods. Specifically, foods high in carbon-13. This was not likely to derive from the consumption of animal flesh, because P. boisei's features are not consistent with carnivorous behavior. The researchers also ruled out C4-rich grasses based on jaw morphology. Instead, they note that the biomarker signatures indicate C3 sedges growing in the wetland area from which the samples were sourced.

The authors write, "Alternative foodstuffs with abrasive, 13C-enriched biomass include seedless vascular plants such as ferns and lycophytes. Ferns are widely distributed throughout eastern Africa in moist and shaded microhabitats and are often found near dependable sources of drinking water."

Other biomarkers imply that early hominin species had ranges much larger than the extent of the excavated sites at Olduvai Gorge; imagine attempting to infer the personal habits of an individual based, for instance, on the evidence of her favorite restaurant. The researchers conclude, "We suggest the spatial patterns defined by both macro- and molecular fossils reflect hominins engaged in social transport of resources, such as bringing animal carcasses and freshwater-sourced foods from surrounding grassy or wetland habitats to a wooded patch that provided both physical protection and access to water."

More information: Clayton R. Magill et al. Dietary options and behavior suggested by plant biomarker evidence in an early human habitat, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2016). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1507055113

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

© 2016 Phys.org