A time-lapse photograph of the CIBER rocket launch, taken from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia in 2013. This was the last of four launches of the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment (CIBER). Sub-orbital rockets are smaller than those that boost satellites to orbit, and are ideal for making quick astronomy observations above Earth's atmosphere. This photo shows a time-lapse capture of the first three stages of the Black Brant XII class rocket at the time of launch. Credit: T. Arai/University of Tokyo

A NASA sounding rocket experiment has detected a surprising surplus of infrared light in the dark space between galaxies, a diffuse cosmic glow as bright as all known galaxies combined. The glow is thought to be from orphaned stars flung out of galaxies.

The findings redefine what scientists think of as galaxies. Galaxies may not have a set boundary of stars, but instead stretch out to great distances, forming a vast, interconnected sea of stars.

Observations from the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment, or CIBER, are helping to settle a debate on the origins of this background infrared light in the universe, previously detected by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope: Whether it comes from these streams of stripped stars too distant to be seen individually, or from the first galaxies to form in the universe.

"We think stars are being scattered out into space during galaxy collisions," said Michael Zemcov, lead author of a new paper describing the results from the rocket project and an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "While we have previously observed cases where stars are flung from galaxies in a tidal stream, our new measurement implies this process is widespread."

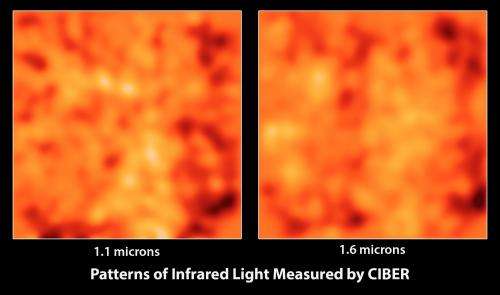

These images from the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment, or CIBER, show large patches of the sky at two different infrared wavelengths (1.1 microns and 1.6 microns) after all known galaxies have been subtracted out and the images smoothed to enhance the large structures. CIBER sees similar patterns at different wavelengths, supporting the idea that the light patterns arise from the same source. The CIBER team used multiple rocket flights to carefully account for all of the infrared emissions in our solar system and from the Milky Way to show that the light is coming from outside our own galaxy. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Using suborbital sounding rockets, which are smaller than those that carry satellites to space and are ideal for short experiments, CIBER captured wide-field pictures of the cosmic infrared background at two infrared wavelengths shorter than those seen by Spitzer. Because our atmosphere itself glows brightly at these particular wavelengths of light, the measurements can only be done from space.

"It is wonderfully exciting for such a small NASA rocket to make such a huge discovery," said Mike Garcia, program scientist from NASA Headquarters. "Sounding rockets are an important element in our balanced toolbox of missions from small to large."

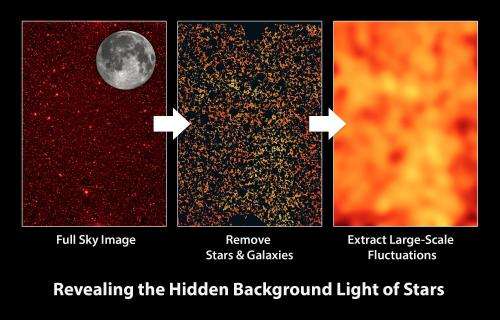

During the CIBER flights, the cameras launch into space, then snap pictures for about seven minutes before transmitting the data back to Earth. Scientists masked out bright stars and galaxies from the pictures and carefully ruled out any light coming from more local sources, such as our own Milky Way galaxy. What's left is a map showing fluctuations in the remaining infrared background light, with splotches that are much bigger than individual galaxies. The brightness of these fluctuations allows scientists to measure the total amount of background light.

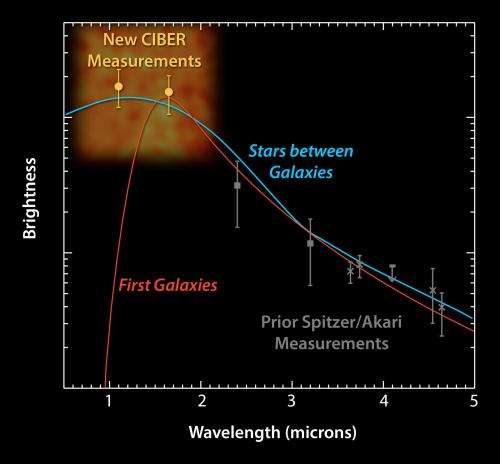

To the surprise of the CIBER team, the maps revealed a dramatic excess of light beyond what comes from the galaxies. The data showed that this infrared background light has a blue spectrum, which means it increases in brightness at shorter wavelengths. This is evidence the light comes from a previously undetected population of stars between galaxies. Light from the first galaxies would give a spectrum of colors that is redder than what was seen.

Observations from NASA's Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment, or CIBER, have shown a surprising surplus of infrared light filling the spaces between galaxies. How did the CIBER team measure this mysterious light? The CIBER data consist of maps of splashy background infrared light, which represent large-scale fluctuations in brightness. By measuring the brightness of these fluctuations, the scientists can estimate the total amount of light. To understand this, imagine trying to estimate the volume of ice in a collection of icebergs dotting a sea. You can't see below the surface, but can look out at the tips of the icebergs. The bigger the tip, the more iceberg that lies hidden underneath. By measuring the overall pattern of iceberg tips, you could figure out the total amount of ice. In this cartoon, the person in green would estimate more ice than the person in magenta, simply by seeing that the surface is rougher in their pond. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

"The light looks too bright and too blue to be coming from the first generation of galaxies," said James Bock, principal investigator of the CIBER project from Caltech and JPL. "The simplest explanation, which best explains the measurements, is that many stars have been ripped from their galactic birthplace, and that the stripped stars emit on average about as much light as the galaxies themselves."

Future experiments can test whether stray stars are indeed the source of the infrared cosmic glow. If the stars were tossed out from their parent galaxies, they should still be located in the same vicinity. The CIBER team is working on better measurements using more infrared colors to learn how stripping of stars happened over cosmic history.

Results from two of four CIBER flights, both of which launched from White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico in 2010 and 2012, appear Friday, Nov. 7 in the journal Science.

-

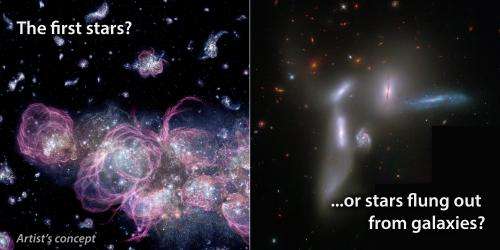

Our sky is filled with a diffuse background glow, known as the cosmic infrared background. Much of the light is from galaxies we know about, but previous Spitzer measurements have shown an extra component of unknown origin. Researchers have proposed two competing theories for the source of this light, including the very first galaxies and black holes (left, artist's concept), or collections of stars tossed out from galaxy collisions (right, Hubble image). The flung-out stars are produced later in the history of the universe than the first galaxies. An example of such a tidal stripping process can be seen in the image from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, where billions of stars, too faint to be seen individually, are torn from their parent galaxies in milky tidal streams. New evidence from NASA's Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment, or CIBER, strongly suggests that the glow is not from the first galaxies, but is better explained by stars tossed out during the assembly of galaxies. Credit: Left: Adolf Schaller for STScI; Right: Hubble Legacy Archive, NASA, ESA; Processing: Judy Schmidt

-

This graphic illustrates how the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment, or CIBER, team measures a diffuse glow of infrared light filling the spaces between galaxies. The glow does not come from any known stars and galaxies; instead, the CIBER data suggest it comes from stars flung out of galaxies. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

-

This plot shows data from the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment, or CIBER, rockets launched in 2010 and 2012. The experiment measures a diffuse glow of infrared light in the sky, known as the cosmic infrared background. CIBER sees shorter wavelengths of infrared light than NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and Japan's AKARI satellite, which have made similar measurements at longer infrared wavelengths in the past. The plot reveals that this background infrared light has a "blue" spectrum, which means that it increases in brightness at shorter wavelengths. The brightness of the CIBER signal, and its blue color, were a surprise to astronomers, and indicate that the emission did not come from the first galaxies in our universe, as previously proposed. The first galaxies would have produced a redder spectrum that drops off steeply at the shorter wavelengths, as indicated by the red line. Instead, the CIBER data fit a model that says the background light is best explained by stray stars between galaxies, as shown by the blue line. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

-

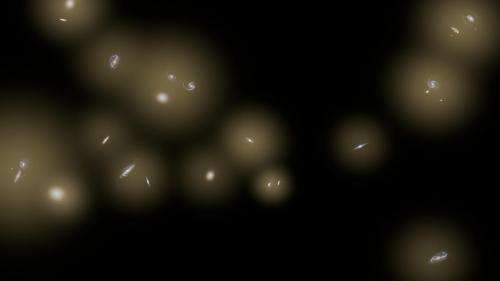

his artist's concept shows a view of a number of galaxies sitting in huge halos of stars. The stars are too distant to be seen individually and instead are seen as a diffuse glow, colored yellow in this illustration. The CIBER rocket experiment detected this diffuse infrared background glow in the sky -- and, to the astronomers' surprise, found that the glow between galaxies equals the total amount of infrared light coming from known galaxies. This means a large number of stars may be flung out as galaxies collide and merge in the process of galaxy assembly. This process of flinging out stars is thought to be more common today than in our universe's distant past. Our own Milky Way galaxy will collide with the Andromeda galaxy in about 5 billion years, tossing stars out into space. Though the process is gravitationally chaotic, the stars are far away from each other and will not directly collide. NASA/JPL-Caltech

More information: phys.org/news/2014-11-caltech-rocket-cosmic.html

Journal information: Science

Provided by NASA