Credit: AI-generated image (disclaimer)

Sitting by the edge of a river on a lazy summer's day, the sky is a beautiful blue overhead. Lush greenery crowds the bank. The river is alive: minnows, coots and water voles fuss at the water's edge.

Amid this truly delightful scene, most eye-catching of all are the brilliant flashes of blue: on the bodies of dragonflies, the wings of mallard drakes, and the eye-catching feathers of any fast-gliding kingfishers that patrol the river.

These creatures gleam with the same distinctive blue we see in peacock plumage and Amazon butterflies. It's a jewel-like, metallic hue that serves a particular purpose: to help these creatures stand out against their comparatively dull environment.

But how do these plants and animals acquire their magical blue shimmer? A true blue pigment is actually relatively rare in nature, so plants and animals instead perform tricks with the light to generate this dazzling effect.

Complicated molecules

In the natural world, we come across blue pigments less frequently than red, green or black pigments, because molecules that reflect blue light are inherently more complicated.

To produce any particular color, molecules must absorb all the light they don't reflect. For blue pigments this means absorbing red light, which has lower energy than blue light. But low-energy light is harder to absorb, so any molecule that reflects the color blue has to work harder to absorb red light.

Credit: AI-generated image (disclaimer)

Molecules which accommodate this process are large and complicated, making them more resource-heavy for organisms to produce. That's why they're less likely to turn up and persist through the long slog of evolution—they're often too costly for organisms to maintain in the survival of the fittest.

Many plants and animals which are blue have evolved this way for an important reason—perhaps to entice a particular pollinator, attract a mate or warn off a predator. For example, cornflowers are blue in order to attract insect pollinators, and use a complex arrangement of molecules to adapt the molecule that makes roses red so that it instead reflects blue light.

A trick of mother nature

Instead of evolving complex molecules that can absorb red light, nature has produced another trick that produces the color blue—the process we have to thank for the iridescent blues that constitute so much of the living world's blueness.

Shimmering blue biological materials are made of the same ingredients as any beetle's back, bird's feather or plant's fruit (mostly the biomolecules chitin, keratin and cellulose, respectively). But these materials are essentially transparent. It's the structure of their surfaces that makes them appear blue.

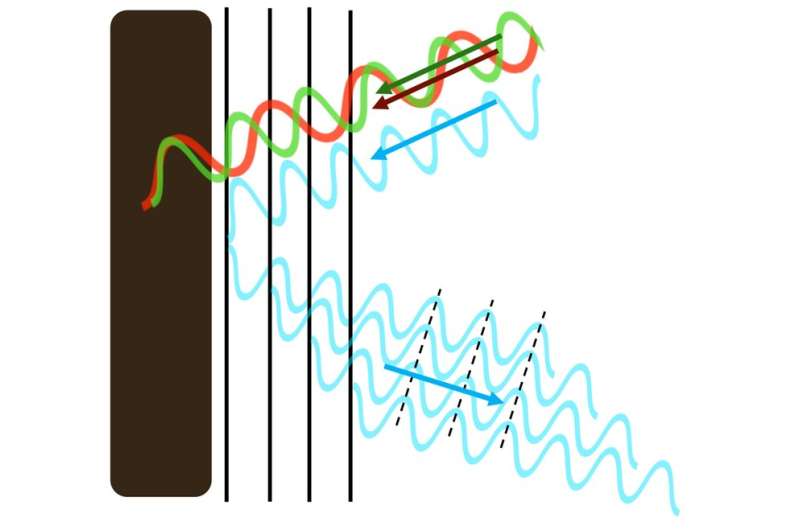

Rather than smooth and continuous material, such surfaces are structured with layers and ridges—or tiny spheres. These patterns create new surfaces that interact differently with the light that hits them.

Certain material structures reflect only blue light, doing so more powerfully than normal pigments. Credit: Rox Middleton, Author provided

These repeating patterns are so small that a single wavelength of blue light, which is just 450 nanometres wide, spans two pattern elements. It's this match, between the microscopic material patterning and the width of a wavelength of light, that is crucial in deciding which colors of the spectrum are reflected back to the naked eye.

The size of nature's microscopic patterning has been honed by evolution to perfectly synchronize with blue light. Even though only a small portion of blue light is reflected, with the rest passing through the transparent material, the additive effect is so strong that only a few repeats of the pattern reflect the maximum amount of blue light—two or three times stronger than pigment reflections. The rest of the colors in white light are mopped up by black pigment that lies underneath the surface.

This astonishing effect is found in every shimmering material. It's present on beetles, seaweed, fruit, magpies, begonias, and even in the glimmer of bullseye flowers.

Although this spectacular effect can produce any color at all—by changing the spacing of the pattern elements—it is remarkably prevalent in blue.

Producing these apparently complex surfaces is actually simpler than producing natural pigment molecules that can absorb red light. It's so effective, in fact, that the resultant brilliant, shimmering blue graces hundreds of different surfaces throughout the natural world.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()