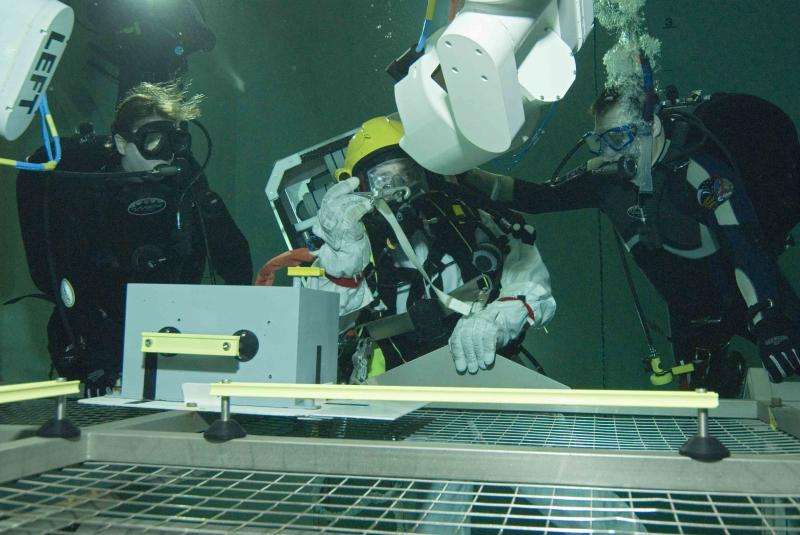

Eurobot is prepared for the Neutral Buoyancy Facility at the European Astronaut Centre (EAC), in Cologne, Germany. Credit: ESA - S.Koenen

An underwater robot initially built to help astronauts train for life in weightlessness is now being tested in the Mediterranean Sea. One day, robots like this may carry out sophisticated missions on our ocean floors, from finding lost aircraft blackboxes to mining minerals or maintaining the sites of ancient pirate shipwrecks.

In space stations, robots are playing an increasingly important role. These days, if an astronaut needs to carry out a minor fix, it might well be that a mechanical arm hands them their tools.

But human–robot teamwork in weightlessness can be tricky. If the astronaut is unused to working with a mechanical arm, the tool might go floating off.

So when ESA decided to build a robot assistant they wanted a way for astronauts to practise grasping tools proffered in space – before ever leaving Earth.

Working with Italy's Thales Alenia Space, ESA built a replica – the Eurobot Wet Model – and put it in a swimming pool for astronauts gain experience with the robot in weightlessness.

With experience developing robotic manipulators, Italian company Graal Tech came onboard to help. Their robot has three limbs, each of which does double duty as a walking leg or a grasping arm.

Next, they covered the robot with floatation devices. "We had to add a lot of 'fat,' to each single arm," said Graal Tech's Alessio Turetta. "In the end it looked like the Michelin Man."

While this created a robot with neutral buoyancy in each and every part, it was too fat and difficult to manoeuvre.

"It's just like an overweight person," said Alessio. "One leg rubbed against the other."

To solve this, the team tinkered with its movement pattern. They introduced a 'crab walk' that gave the limbs all the room they needed. It worked: Graal Tech's robot has been used ever since by astronauts practising in the pool at ESA's European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany.

Two Maris underwater robot handling an object underwater, each one with one of Graal Tech’s ‘astronaut arms.’

From space to under the sea

Working in space led the companyto take to the seas. After the ESA project ended, in 2006, Graal Tech capitalised on the underwater expertise.

Most existing underwater robots on the market are hydraulic. While they offer strength, they have relatively little fine control. Graal Tech's is electric-powered, however, capable of both fine movement and targeted actions.

"We realised that our ESA astronaut robot technology was good enough to commercialise," said Alessio. With the help of European Commission funding, they did just that.

One of the first requests came from Giuseppe Casalino, robotics professor at the University of Genoa in Italy. He wanted to prototype a robot that might one day scour the ocean's floor for archaeological itemsor even a blackbox from a lost aircraft.

He liked the electrical arms developed for the Eurobot Wet Model because of their ability to perform precise tasks, without compromising too much on strength.

"Strong but blunt hydraulic lifts exist for heavy-duty operations," explained Giuseppe. "There is also equipment out there for biologists, and archaeologists, who need very fine work. We believed something in between should be developed."

As part of three EC-funded projects, Graal Tech began working with Giuseppe and his team.

Graal Tech's 'astronaut arm' mounted on an underwater vehicle and successfully recovering an item on the seafloor. Credit: Genoa Robotics and Automation Laboratory, University of Genova

Attaching a Graal Tech 'astronaut arm' to an underwater vehicle, the first goal was to create a system that could work autonomously underwater on different grasping tasks. This was tested successfully at depths of 10–30 m in the Mediterranean Sea near the Balearic Islands.

Now, the Italian Maris national project is testing two separate vehicles each equipped with one of the special arms. They grasp large objects, manipulate them and carry them from one place to another, underwater.

An imminent oil and gas project will be equipped with one or two arms.

"Commercial applications are foreseen," continues Giuseppe. "The oil and gas industry need this to cut costs." Tests will be carried out in the North Sea or the Mediterranean, some 500 m deep within a year.

Eurobot could play an important role in EVA support on the International Space Station. Here, the Eurobot Web Model hands a tool to an astronaut training at ESA’s European Astronaut Centre pool in Cologne, Germany. Credit: ESA - Helmut Rub

Finally, an underwater mining project, Robust, has just been given the green light for EC funding. "Underwater mining is a very promising field, which is expected to grow in the near future," Giuseppe adds.

Noting that working underwater poses challenges similar to those encountered in space, Alessio and Giuseppe both believe that underwater robots might one day be used for many dangerous tasks currently performed by human divers, such as maintaining offshore plants and inspecting ocean pipes.

For Graal Tech, these developments are very welcome. Alessio credits ESA with having played a central role in the creation of their underwater arm, "We can say our experience with ESA was the start of it all. Without the space development, we would not have such a great arm now."

-

Thumbs up from ESA astronaut Jean-François Clervoy after successful completion of the Eurobot Wet Model trial. Credit: ESA - S.Koenen

-

Graal Tech ‘astronaut arm’ mounted on the underwater Trident robot. Credit: Genoa Robotics and Automation Laboratory, University of Genova

Provided by European Space Agency