Credit: AI-generated image (disclaimer)

Human made noise, also called anthropogenic noise, is rising in many environments due to the increase in transportation and the exploration for and exploitation of energy sources.

North Western Australia, in particular as the most active area of the country in terms of oil and gas exploration and coastal construction activities, is filling WA's coastline with added background noise.

In the extreme, anthropogenic noise can destroy the vulnerable sensory tissues, in the inner ear and the lateral line systems of fishes.

This may ultimately lead to death if the animals lose their ability to hear or detect hydrodynamic changes.

Noise can also be a source of acute or chronic stress, which may affect behavioural and sensory functions.

Besides, a loud sound can mask important biological sounds, essential to marine organisms in communication, finding prey and mates and detecting predators.

More than 100 species of sharks and rays live in WA waters, ranging from the tiny pygmy shark (Euprotomicrus bispinatus) to the iconic whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the world's biggest fish.

Sharks, like bony fishes, possess an inner ear and a lateral line, which are sensitive to underwater vibrations and sounds.

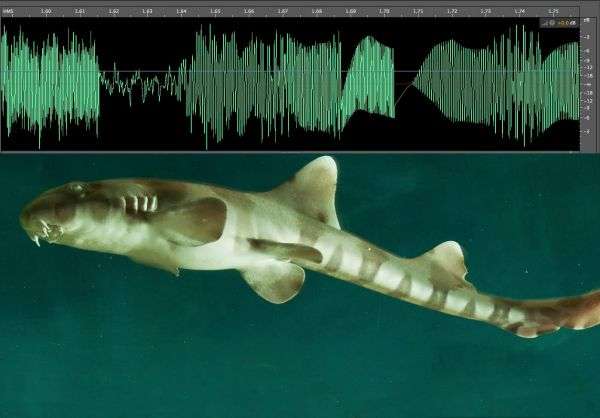

Brown banded bamboo shark. Credit: Paul Ricketts/UWA

Compared to marine mammals, sharks have a very narrow hearing range but are known to be particularly sensitive to very low frequencies.

This hearing range overlaps with most of the anthropogenic sound produced by seismic airgun arrays, dredging, pile driving and shipping.

Some sharks are migratory and can potentially leave a disturbed area, for example great whites (Carcharodon carcharias), tigers (Galeocerdo cuvier) and whale sharks.

However most of the species, such as wobbegong (Orectolobidae), bamboo (Hemiscylliidae) and Port Jackson sharks (Heterodontus portusjacksoni), stay in a single location or patch of reef or change habitats only when they reach a critical part of their lifecycle like most reef sharks do.

Sound pollution represents a particular threat for those sedentary sharks, as they would typically not leave the area during a high intensity sound event.

In an effort to fill these vital knowledge gaps, the Neuroecology Group which is part of the UWA Oceans Institute and School of Animal Biology is studying the effects of sounds on sharks.

Our first strategy is to assess their sensitivity to sound such as what frequencies and intensities the different species react to, with electrophysiological techniques in the laboratory.

Assessing the hearing sensitivity of a Port Jackson shark in the lab. Credit: Paul Ricketts/UWA

We will then partner with industry to assess and characterise the different anthropogenic sounds that are 'ensonifying' our waters.

We can then assess the potential overlap, comparing the ambient soundscape with the auditory abilities of local shark species and identify any threats of local sound sources to the local shark populations.

Finally, and most importantly the behaviour of wild animals and their responses to different anthropogenic noise needs to be observed and examined to establish any short- and long-term effects.

It is a big challenge, as we are examining wild animal movement in their natural habitat and needing to observe and quantify their responses before, during and for an extended period after exposure to particular sounds.

However, at this stage, the specific regulation on anthropogenic noise in Australia covers only a few species of marine mammals.

We feel there is a dire need and a responsibility to fill a large knowledge gap, to inform management practises and policy and broaden the regulatory framework to include the effects of noise pollution on a wider range of marine species, including sharks and their relatives.

Provided by Science Network WA