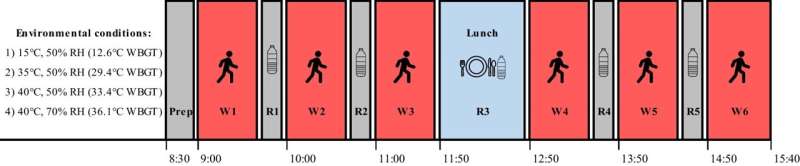

Schematic representation of the experimental protocol. After arrival and instrumentation (Prep), work cycle 1 (W1) began. All work cycles (W1–6) were 50 min in duration and were separated by a 10-min rest interval (R1–5) in a temperate environment (21 °C, 50% RH). During rest intervals, ad libitum water intake was permitted and quantified for later analysis. The standardized lunch period between work cycles 3 and 4 lasted 1 h. Each participant completed the protocol in all four environments listed in the figure, in a counterbalanced order. Credit: International Journal of Biometeorology (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s00484-022-02370-7

It is predicted that the planet's average temperature could be between 2 and 9.7°F (1.1 to 5.4°C) warmer in 2100 than it is today. But what impact would this increase in temperature have on the global workforce?

Researchers at Loughborough University, led by Professor George Havenith, Director of the Environmental Ergonomics Research Center (EERC), have been investigating the impact of heat exposure on physical work capacity as part of the international HEAT-SHIELD project.

The Horizon 2020 study is examining the negative impact of increased workplace heat stress on the health and productivity of five strategic European industries: manufacturing, construction, transportation, tourism and agriculture.

In its latest research paper, the EERC team investigate the interactions between work duration and heat stress severity.

Prior to this study models looking at the impact of high workplace temperatures on physical work capacity (PWC) have been based on one-hour exposure times. In a world-first, the Loughborough team have examined the impact of heat stress exposure on PWC during a full simulated work shift, consisting of six one-hour work-rest cycles in the heat across a working day.

For the study nine healthy males completed six 50-min work bouts, separated by 10-minute rest intervals and an extended lunch break, on four separate occasions: once in a cool environment (15°C/50% relative humidity) and in three different air temperature and relative humidity combinations (moderate, 35°C/50% relative humidity; hot, 40°C/50% relative humidity; and very hot, 40°C/70% relative humidity). This range of hot temperatures and conditions covers those already experienced by more than one billion workers across the globe.

To mimic a moderate to heavy physical workload, work was performed on a treadmill at a fixed heart rate of 130 beats-a-minute. During each work bout, PWC was quantified as the energy expended above resting levels.

The research team found that in addition to the reduction already observed in the earlier 1-hour trials, over the course of the simulated shift, work output per cycle decreased even more, even in the cool climate, with the biggest reduction after the lunch break and meal consumption.

On top of the reductions due to heat observed in the short 1-hour tests (30, 45 and 60% for the three climates), relative to the work output in the cool climate, there was on average an additional 5%, 7%, and 16% decrease in PWC when work was performed across a full work shift for the moderate, hot, and very hot conditions respectively. Overall this equates to a 35% decrease in productivity throughout the workday when operating at temperatures of 35°C/50% relative humidity, going up to a 76% reduction when the thermometer reaches 40°C/70%relative humidity.

Speaking about the study, Professor Havenith said, "These findings enhance our current understanding of the consequences of extended occupational heat exposure and provide evidence that can be used to more accurately predict the socio-economic burden of future extreme heat.

"A significant drop in productivity will have a significant impact on employee welfare and business output. It is yet further evidence of why action should be taken now to stop global warming, the effect of which is already being felt hardest by those in the Global South."

The latest paper, "Quantifying the impact of heat on human physical work capacity; part IV: interactions between work duration and heat stress severity," has been published in the International Journal of Biometeorology.

It follows two Lancet publications which provided guidance on the impact of heat and on how to best deal with it, and a series of papers which have assessed the impact of a heating world on productivity in physical work.

More information: James W. Smallcombe et al, Quantifying the impact of heat on human physical work capacity; part IV: interactions between work duration and heat stress severity, International Journal of Biometeorology (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s00484-022-02370-7

Journal information: International Journal of Biometeorology , The Lancet

Provided by Loughborough University