Listeners can extract a lot of information about a person from their acoustic speech signal. During the 179th ASA Meeting, Dec. 7-10, Tessa Bent, Emerson Wolff, and Jennifer Lentz will describe their study in which listeners were told to categorize 144 unique audio clips of monolingual English talkers into Midland, New York City, and Southern U.S. dialect regions, and Asian American, Black/African American, or white speakers. Credit: Tessa Bent, Emerson Wolff, and Jennifer Lentz

Listeners can extract a lot of information about a person from their acoustic speech signal. When researchers previously put this to the test, listeners were able to identify both race and regional dialects within the U.S. with moderate to high accuracy.

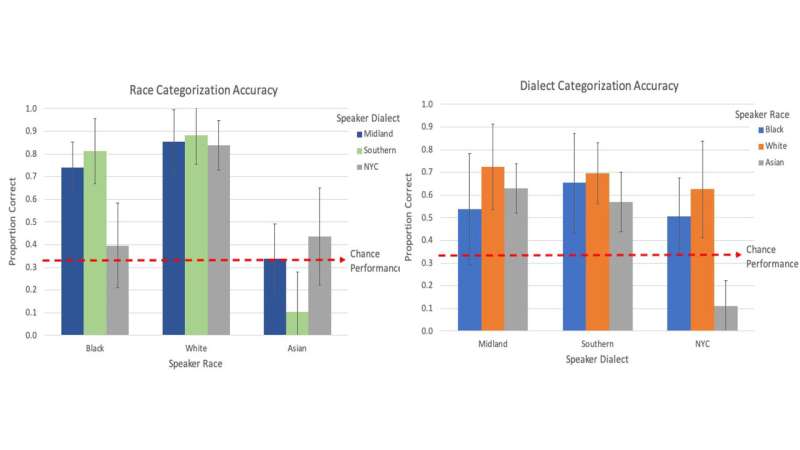

During the 179th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, which will be held virtually Dec. 7-10, Tessa Bent, Emerson Wolff, and Jennifer Lentz, of Indiana University, will describe their study in which listeners were told to categorize 144 unique audio clips of monolingual English talkers into Midland, New York City, and Southern U.S. dialect regions, and Asian American, Black/African American, or white speakers. Their poster session, "Categorization of U.S. regional dialects and race from speech," will begin at 1:05 p.m. on Dec. 10.

"Prior research generally suggests listeners are better at identifying a talker's race than their regional dialect," Bent said. "And while many race identification experiments only use two categories, such as Black or white, most dialect work uses more than two categories."

The researchers were not sure what to expect with dialect identification results, because many other studies did not vary the speaker's race when exploring dialect identification—for example, all white speakers from different dialect areas.

"Our results were a bit surprising but do support prior findings," she said.

For this study, listeners were presented with stimuli and identified a speaker's race or regional dialect.

"The results showed slightly higher accuracy for race identification than regional dialect, with white Southern talkers most accurately identified by race and white Midland talkers most accurately identified by dialect," Bent said.

A listener's social network likely influences their identification of race.

"Our participants mostly identified as white and reported having much more daily interaction with people who identified as white than as Asian, Black, or other races," she said.

In follow-up work, Bent and colleagues plan to recruit listeners who identify as Asian, Black, or white from specific regions to address the question of how experience impacts perception of race and dialect.

"It will be very interesting to see if listeners with more experience with certain race or dialect combinations are better at the identification tasks," she said.

More information: acousticalsociety.org/technical-program/

Provided by Acoustical Society of America