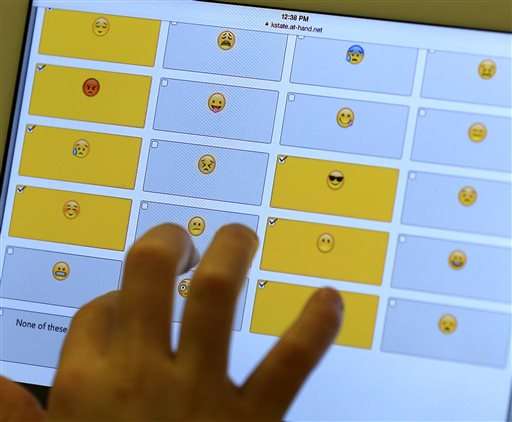

In this Feb. 15, 2016 photo, a student demonstrates how emojis are used during a research session on the Kansas State University campus in Olathe, Kan. The Sensory and Consumer Research Center at Kansas State University-Olathe is developing a scientific methodology to measure children's responses to food using face emojis. (AP Photo/Orlin Wagner)

The smiling, blissful and confused-looking emojis dotting the electronic landscape may hold the key to ferreting out grade-school children's true feelings about foods, Kansas researchers say, and could help schools across the nation cut down on lunchroom food waste.

Most school lunch programs in the U.S. already do taste tests, but their efforts pale in comparison to the scope of the research project at the Sensory and Consumer Research Center at Kansas State University Olathe, which is developing a scientific methodology to measure children's face-emoji responses to food. So far, kids in Kansas and Ghana have been the guinea pigs.

The goal is to create an "emoji ballot" that's "applicable internationally across cultures, across countries," said Marianne Swaney-Stueve, who manages the center. "And there really is no language barrier." The researchers also hope it will help schools pick foods that children will eat and help manufacturers make products that schools will want to buy.

Food waste has been more of an issue in the United States since new federal nutrition regulations were implemented in 2012 that mandated healthier products in school lunches. For example, more than 26 percent of the food budget at Boston's middle schools was discarded by students, according to a study cited by the nonprofit School Nutrition Association. If translated nationwide, that would be more than $1.23 billion of school food wasted each year.

In this Feb. 15, 2016 photo, a student demonstrates how emojis are used during a research session on the Kansas State University campus in Olathe, Kan. The Sensory and Consumer Research Center at Kansas State University Olathe is developing a scientific methodology to measure children's responses to food using face emojis. (AP Photo/Orlin Wagner)

Already, about three-quarters of U.S. school districts are doing taste tests with students and nearly all have implemented initiatives such as nutrition education or locally grown foods in an effort to make meals more appetizing, according to an association survey of 1,100 schools conducted last year.

"School nutrition professionals are always looking for new ideas to promote healthier choices to students ... to find ways to get more student feedback so they can develop kid-approved menus that are healthy and also appealing to students," association spokeswoman Diane Pratt-Heavner said.

Despite those efforts, government data shows more than 1 million fewer students are choosing school lunches.

The emoji methodology research, which began in 2014, first started with focus groups of children ages 7 to 11 in Olathe.

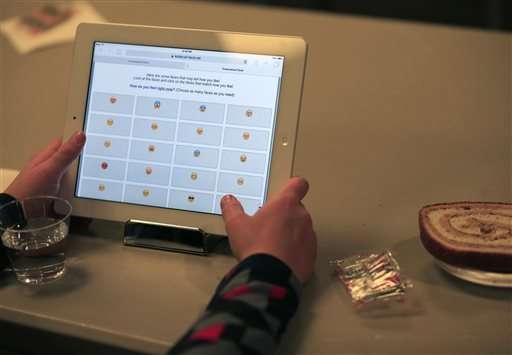

In this Feb. 15, 2016 photo, graduate research assistant Katy Gallo assists students at the research center on the Kansas State University campus in Olathe, Kan. The smiling, winking and crying emojis dotting the electronic landscape may hold the key to ferreting out grade-school children's true feelings about foods. Kansas researchers say that could help schools across the nation cut down on lunchroom food waste. (AP Photo/Orlin Wagner)

Children in the focus group tasted and rated three foods: plain oatmeal, pepperoni pizza Lunchables and Japanese Ramune soda. The premise was to have food that was boring, familiar and an "out-of-the-box" item that participants had not likely encountered—the sweet, strawberry-flavored soda is packaged in a bottle with a marble that releases carbon dioxide—to provide a baseline comparison for testing responses to other foods.

The Lunchables were well-liked, but the soda was "polarizing" because some thought it tasted like medicine, doctoral student Katy Gallo said. The children also rated the oatmeal disappointing because it lacked flavor, though some were hungry and ate all of it anyway.

Researchers used those results to determine which emojis and words the children used and which ones were confusing, then questioned them about their favorite foods and how those made them feel. They narrowed down students' choices to 28 face emojis and 28 words.

In a later taste test, researchers had the children emoji-rate other foods. They had particularly positive emoji responses, pointing to the grinning face, smiling face with smiling eyes or a smile with the tongue out, to the chocolate graham snacks, orange juice, white bread and white grapes. The least-liked food tested, earning a worried face, confused face or confounded face: fresh spinach.

In this Feb. 15, 2016 photo, a student demonstrates how emojis are used during a research session on the Kansas State University campus in Olathe, Kan. The Sensory and Consumer Research Center at Kansas State University Olathe is developing a scientific methodology to measure children's responses to food using face emojis. (AP Photo/Orlin Wagner)

Brenan Kuzmic, an 11-year-old, said the emojis made it easier for him to communicate. Chocolate graham snacks won a smiley face from him, while the fresh spinach earned just a "normal face," he said.

Similar polling was done with 12-year-old students at 10 schools in Accra, Ghana, to see if cultural differences existed in emoji use.

"They are at an age where they have opinions, and sometimes they don't feel like they are being heard," Gallo said of all the students. "And so they really appreciate being able to give that kind of feedback."

Researchers will return to Ghana for the next phase of testing this month, followed by similar taste tests in Olathe in May. They also plan to further narrow the number of emojis kids can choose.

The school lunch program at Ashburn, Virginia-based Loudoun County Public Schools, north of Washington, D.C., has used three emojis—one with a big smile, another with a straight line for a mouth and one with a frown—at taste parties for years, said Becky Domokos-Bays, supervisor of school nutrition services.

Domokos-Bays, who's also president-elect for the School Nutrition Association, was intrigued by the Kansas research, saying she would "absolutely" be interested in using that emoji methodology with her students.

"Our opinion doesn't count so much as theirs does," Domokos-Bays said. "Because they are the ones who are eating."

© 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.