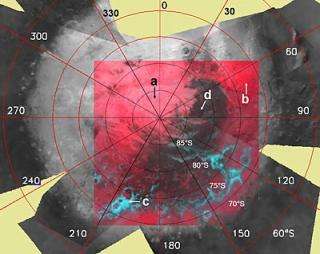

This mosaic image was built from ten observations by the OMEGA Visible and Infrared Mineralogical Mapping Spectrometer on board ESA’s Mars Express, when the spacecraft was flying at about 6000 kilometres altitude over the south pole during the Martian early to mid-Spring. The dark region within the bright seasonal cap below and to the right of the pole is the so-called ‘cryptic region’ on Mars. During Southern spring, this area ‘mysteriously’ become much darker than the rest of the seasonal ice cap, notwithstanding temperatures as low as -135º C which should correspond to the presence of bright carbon dioxide ice, or ‘dry ice’, on the surface. The colour scheme in this area indicates the presence of carbon dioxide ice in reddish tones, and the presence of water ice in bluish tones. OMEGA observations have revealed that there is a thick slab of dry ice in this area, but its surface is heavily covered by dust. Such dust contamination may result from the sunlight passing through the clear ice and heating the soil underneath. This would cause pressure to build up in carbon dioxide bubbles below the ice until a geyser erupts throwing dust onto the surface. The letters indicate regions with different surface compositions and texture (a: bright, fine-grained “dry ice”; b: larger grained “dry ice” which is not quite as bright; c: water ice frost; d: cryptic region). The greyish tones in the cryptic region indicate that the surface is heavily contaminated by dust. This image was first published in the scientific journal Nature (Nature 442, 790-792, 17 August 2006) doi:10.1038/nature05012).

Mars Express's OMEGA instrument has given planetary scientists outstanding new clues to help solve the mystery of Mars's so-called 'cryptic region'.

In the 1970s, orbiter missions around Mars revealed that during southern spring, large areas near Mars's south pole became much darker than the rest of the seasonal ice cap. How could this area be in the polar region and not be covered in bright ice?

Intrigued, planetary scientists called the area the 'cryptic region' of the south seasonal cap. The mystery deepened in the late 1990s when new observations showed that the temperature of the cryptic region was close to -135є Celsius. At that temperature, carbon dioxide ice had to be present. So, scientists developed the idea that a one-metre-thick slab of clear carbon dioxide ice covered the cryptic region, allowing the dark surface underneath to be seen.

However, the new observations from Mars Express's OMEGA instrument show that this interpretation cannot be correct. OMEGA measures the amount of visible and infrared radiation bouncing off the Martian surface. In so doing, it detects minerals and ices on the surface by charting the specific wavelengths of radiation they absorb.

Carbon dioxide ice (dry ice) absorbs infrared light strongly at specific wavelengths. "We see only weak absorptions in the infrared, which would indicate little carbon dioxide ice in the cryptic region," says Yves Langevin, Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale, Orsay, France, who led the analysis of the OMEGA results.

The only way to reconcile the apparently conflicting observations is that there is indeed a thick slab of dry ice in this area, but its surface is so heavily covered by dust that few of the Sun's rays make it to the deeper layers and back again.

How does the dust get on top of the slab? The answer could be provided by the mysterious markings that dot the cryptic region. Known as spots, 'spiders' and 'fans' depending upon their shapes, they were discovered in 1998–1999 by NASA's Mars Global Surveyor.

Planetary scientists believe they are caused by sunlight passing through the clear ice and heating the soil underneath. This causes pressure to build up in carbon dioxide bubbles below the ice until a geyser erupts throwing dust onto the surface, creating the spots and fans. In this model, the spiders result from erosion of the underlying surface by rapid gas flows below the ice. Langevin believes that this process could significantly contribute to the dust contamination of the icy surface, which OMEGA observed.

"In terms of physics, this is a straightforward process and would go a long way towards explaining our observations," says Langevin. However, there are major questions remaining, such as why are spiders, spots and fans only observed in a small fraction of the cryptic region? And why are areas not covered by spots and fans already relatively dark.

To clarify these points, Langevin must wait until the next southern spring equinox on Mars, in 2007. During the long winter, the Sun cannot be seen from the south pole and a pristine layer of ice should build up over the cryptic region. Langevin wants to observe the cryptic region close to the spring equinox, before the Sun has touched it and started the venting process. This will tell him when the dust geysers form and whether they are the ice slab's only source of dust contamination.

So, whilst not as cryptic as it once was, Mars's south polar region still has a few mysteries left.

Source: ESA