May 7, 2019 feature

Synthetic and living micropropellers support convection-enhanced nanoparticle transport

Nanoparticles (NPs) are a promising platform for drug delivery to treat a variety of diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disease and inflammation. Yet the efficiency of NP transfer to the diseased tissue of interest is limited due to an assortment of physiological barriers. One significant hurdle is the transport of NPs to precisely reach the target tissue of interest. In a recent study, S. Schuerle and a team of interdisciplinary researchers at the departments of Translational Medicine, Biophysics, Engineering Robotics, Nanomedicine and Electronics, in Switzerland, the U.K. and the U.S. developed two distinct microrobot-based micro-propellers to address the challenge.

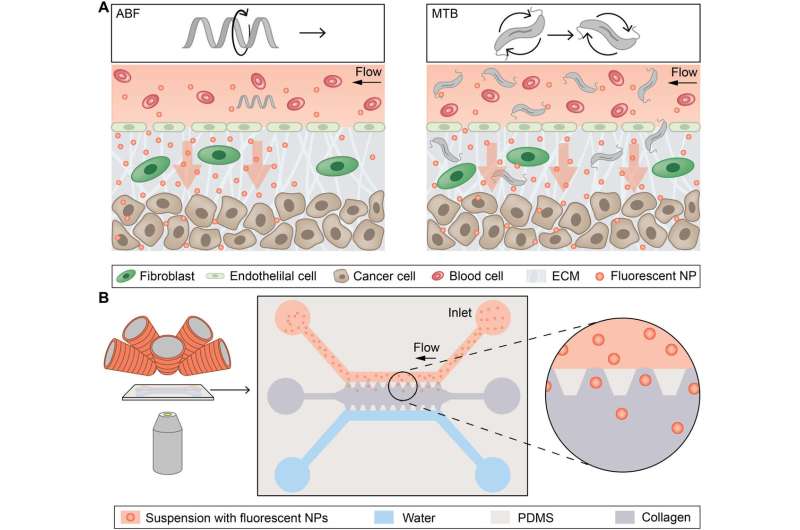

They used rotating magnetic fields (RMFs) to power the devices and create local fluid convection to overcome the diffusion-limited transport of nanoparticles. During the first experimental approach, they used a single synthetic magnetic microrobot as an artificial bacterial flagellum (ABF) and then used swarms of a naturally occurring magnetotactic bacteria (MTB) to create a "living ferrofluid" by exploiting the ferrohydrodynamics. Using both approaches the scientists enhanced the transport of NPs in a microfluidic model of blood extravasation (movement of a drug from blood vessels to the external tissue) and tissue penetration in microchannels surrounded by a collagen matrix to create a biomimetic tissue-vessel interface in the lab. The results of the study are now published in Science Advances.

Nanoparticles (NPs) are increasingly popular in nanomedicine due to biomedical research potential as carriers in drug delivery that surpass the limits of conventional medicine. While NPs are designed to alter the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of existing drugs, they are impeded by physiological barriers, which prevent successful accumulation at the sites of disease, limiting their therapeutic effects in vivo. During cancer therapy, for instance, drug carriers encounter abnormal vessels that surround the tumor architecture for ineffective intravenous drug release.

Since delivering NPs into tissues is strongly influenced by their physiochemical properties, scientists have re-designed the NP shapes and sizes to optimize their transport kinetics through vessel walls to reach tissues. Researchers had previously proposed multistage approaches for optimized drug delivery, either by shrinking nanoparticles in time, or fragmenting them to disperse and reach a site of interest only after encountering microenvironmental cues of disease in vivo.

Generally, NP transport is affected by surface charge, hydrophobicity and surface biochemistry; properties that can be actively optimized in research work for more effective in vivo trafficking. Scientists have used external energy sources such as magnetic and acoustic forces to create wirelessly controlled microbots and shuttle the therapies to diseased tissue for improved diffusive transport. However, these methods still relied on diffusive transport after releasing their onboard cargo, while the need remains for more distinct strategies of transport into a defined location.

In the present work, Schuerle et al. detailed two distinct strategies to generate wirelessly localized convective flow to prevent the invasiveness of implanted nanoparticles. Inspired by the field of microrobots (microbots), the scientists used (1) a single, synthetic, bacteria-inspired microrobot, or (2) large swarms of living bacteria to drive localized NP transport. The artificial and natural micropropellers assisted the process by promoting magnetically driven convection into a defined location in a magnetofluidic setup with potential for therapeutic applications.

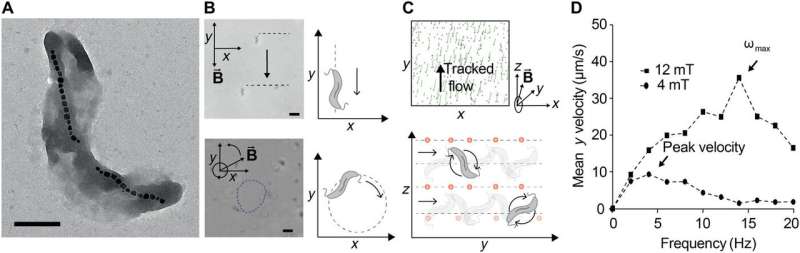

The synthetic microbot imitated bacterial propulsion using an artificial bacterial flagellum (ABF), while the dense swarms of magnetotactic bacteria (MTB) harnessed by Schuerle et al. occurred naturally as gram-negative prokaryotes (Magnetospirillum magneticum) with magnetic properties. The scientists expect the results to overcome existing transport barriers for enhanced NP tissue penetration via wireless control and spatiotemporally precise local convection in the future.

Schuerle et al. engineered the magnetic ABF using three-dimensional (3-D) lithography and metal deposition, as previously reported. The bioinspired microrobots mimicked the rotating flagella for efficient propulsion-based locomotion at the microscale—where viscous drag forces dominate. They controlled the ABF motion with uniform magnetic fields in 3-D rotation using a wireless magnetic control setup containing electromagnets arranged around a single hemisphere.

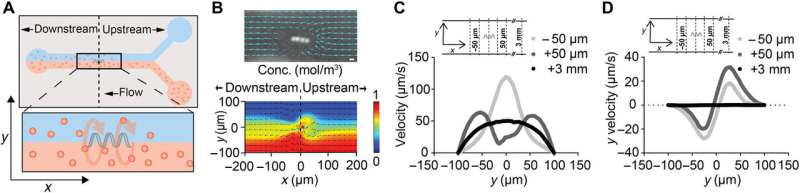

Then they mounted the setup on an inverted microscope to track the movements of the controlled microrobots. The rotating magnetic fields (RMFs) allowed forward propulsion and convective flow in the surrounding fluid and when the scientists immersed the ABF in a suspension of fluorescent NPs, they observed controlled flow for mass transport of the NPs.

In the experiment, they constructed the bottom layer of the microfluidic channel to contain the 200 nm NPs similar to the size used in clinical applications, while on the top fluid layer they maintained a suspension of pure aqueous medium. The scientists stationed the ABF at the center of the setup to sustain its position against the flow by controlling the fluid flow in the setup. This arrangement of the ABF in a microfluidic channel disrupted the laminar flow to produce convection, which transported NPs from the fluid layer at the bottom to the upper layer—to reach the channel wall, i.e., the location of interest.

The scientists also developed a single-fluid flow model in a microchannel to form a bioinspired microvessel with biomimetic scales and fluid flow rates. The model contained concentrated collagen in the center that mimicked the native extracellular matrix. Using the device, Schuerle et al. quantified the fluorescent intensity in the biomimetic matrix to test if the magnetically controlled ABF could enhance the mass transport of fluorescently labelled NPs into the tissue-mimicking matrix. The results indicated that ABFs were limited as a convective micropropller in smaller vessels, but this can be changed by scaling the ABF structure to suit the channel size in the future.

The scientists considered the effects of a whole swarm of smaller microrobot propellers next. For this, Schuerle et al. selected the wild type MTB strain AMB-1 (Magnetospirillum magneticum) to form magnetosomes. The microorganisms naturally produced chains of iron oxide particles in lipid bilayers of the plasma membrane for manipulated movement using external magnetic fields. While researchers had used MTBs in previous studies as potential vehicles of drug delivery with external magnetic fields, Schuerle et al. used rotational magnetic fields (RMFs) in the present work. The RMFs forced the movement of an MTB swarm to drive their motion via magnetic torque.

The scientists lowered the average distance between the bacteria by using a high concentration of MTBs to press the cell neighbors forward in 3-D swarms dominated by hydrodynamic forces. They did not observe clustering or aggregation of the MTB magnetosomes when exposed to RMFs since the magnetosomes were inherently shielded by the bacterial cell membranes for controlled fluid flow. Schuerle et al. repeated the experiments for biomimicry using a microfluidic device containing collagen to show that MTB swarms could penetrate collagen, when sufficiently high concentrations of MTBs were used.

In this way, using two experimental strategies Schuerle et al. improved the mass transport of NPs, via convective flow generated by magnetically controlled micropropellers. The microrobotic experiments showed that ABF mimicked a bacterial flagellum to assist NP accumulation and penetration into a dense collagen matrix – when acted upon by RMFs. Schuerle et al. propose to include such stationary ABFs into stents to trigger drug release and improve penetration at a site of interest to counteract inflammation on demand.

With the second strategy, they focused on generating the same technique but with magnetotactic bacterial strains (MTBs). Based on the present work and the existing tumor-homing properties of MTBs, the scientists envision magnetically controlled swarms of 3-D MTBs to transport NPs in the interstitial fluid space of tumor microenvironments. The scientists will optimize the density of bacteria for a compatible dose in vivo and the work will pave the way forward to further studies on micro- and nanomaterials for magnetically enhanced NP transport in clinical nanomedicine.

More information: S. Schuerle et al. Synthetic and living micropropellers for convection-enhanced nanoparticle transport, Science Advances (2019). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aav4803

R. Blakemore. Magnetotactic bacteria, Science (2006). DOI: 10.1126/science.170679

Ouajdi Felfoul et al. Magneto-aerotactic bacteria deliver drug-containing nanoliposomes to tumour hypoxic regions, Nature Nanotechnology (2016). DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2016.137

Soichiro Tottori et al. Magnetic Helical Micromachines: Fabrication, Controlled Swimming, and Cargo Transport, Advanced Materials (2012). DOI: 10.1002/adma.201103818

Journal information: Science Advances , Science , Nature Nanotechnology , Advanced Materials

© 2019 Science X Network