Materials researchers study the causes of wear – permanent molecular modifications occur at first contact

Wear has major impacts on economic efficiency and health. All movable parts are affected, including such things as bearings in a wind power plants or artificial hip joints. However, the exact cause of wear is still unclear. Scientists of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) recently proved that the effect occurs at first contact, and always takes place at the same point of the material. Their findings could help develop optimized materials and reduce consumption of energy and raw materials. The researchers present results of two studies in the Scripta Materialia.

Friction occurs wherever objects adhere to each other or have sliding or rolling contact. Friction forces cause wear, which results in enormous costs. About 30 percent of the energy consumed in the transportation sector is used to overcome friction. In Germany, friction and wear produce costs corresponding to about 1.2 to 1.7 percent of the gross domestic product, i.e. between 42.5 and 55.5 billion euros in 2017.

It is well known that the friction of rubbing hands makes them get warmer. The reaction of materials to friction is far more complicated. "Here, many things change at the same time. But how exactly this process starts, where wear forms, and what effect friction energy has is hardly understood, as it has been impossible so far to look directly below the surface of the friction partners," says Professor Peter Gumbsch, holder of KIT's Chair for Mechanics of Materials and head of the Fraunhofer Institute for Mechanics of Materials. "With our new microscopic methods, however, we can do so. They reveal a sharp interface in the material, at which the wear particles are detached. We want to find the cause of this material weakness."

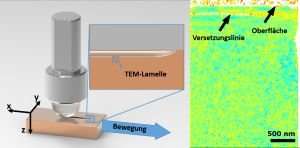

In their experiments, the scientists detected a sharp line at a depth of 150 to 200 nm. It forms at first contact, and is irreversible. It is the source of the later weakness in the material. The scientists tested various materials including copper, brass alloys, nickel, iron and tungsten, and always obtained the same result. "These results are entirely new. We did not expect them," Gumbsch says. The findings contribute to understanding and reproducing processes that take place on the molecular level during friction. "As soon as we understand the effects, we can interfere specifically. It is my objective to develop guidelines for the future production of alloys or materials with better friction properties," Gumbsch adds.

A Wave Forms

The defect in the material is a so-called dislocation. Dislocations are responsible for irreversible deformations. Dislocations result when atoms shift relative to each other. As a result, an atomic wave propagates in the material, similar to the movement of a snake. "We found that these dislocations during friction form the line-shaped structure observed in a self-organized manner. This effect occurred in every experiment," explains Dr. Christian Greiner of KIT's Institute for Applied Materials – Computational Materials Science (IAM-CMS).

The scientists compared the effect observed with the mechanical stress distribution in the material that can be calculated analytically. Calculations confirmed that certain dislocation types self-organize in a stress field at a depth between 100 and 200 nm.

Quicker Oxidation by Friction

In addition to the effect mentioned, the scientists used copper samples to study the effect of friction on oxidation of surfaces. After a few friction cycles, copper oxide spots formed on the surface. In the course of time, they grew to semi-circular nanocrystalline copper oxide clusters. The copper-2-oxide nanocrystals of 3—5 nm in size were surrounded by an amorphous structure. They increasingly grew into the material until they overlapped and formed a closed oxide layer. According to Greiner, this phenomenon has been known for a long time, but the cause of this effect is still unknown. "It is very important to understand how friction-caused oxidation takes place. In materials science, copper is used rather frequently. And copper is also an important material for movable parts," Greiner says. Many bearings consist of copper alloys, such as bronze or brass. Consequently, the study results are of considerable interest to copper processing industries.

Hard Ball Meets Soft Copper

The approach used for both studies is simple: A sapphire ball is moved in a very smooth, slow, and controlled way straight across a plate made of pure copper. The sapphire ball always guarantees the same reproducible contact and friction due to the hardness of sapphire. After every movement across the plate, the researchers measured the deformation it caused, and the resulting structural modifications inside the metals. In their unique approach, they combined friction experiments with non-destructive testing methods, data science algorithms, and high-resolution electron microscopy.

More information: Zhilong Liu et al. Stages in the tribologically-induced oxidation of high-purity copper, Scripta Materialia (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.05.008

Christian Greiner et al. The origin of surface microstructure evolution in sliding friction, Scripta Materialia (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.04.048

Journal information: Scripta Materialia

Provided by Karlsruhe Institute of Technology