Mystery of superior Leeuwenhoek microscope solved after 350 years

Researchers from TU Delft and Rijksmuseum Boerhaave have solved an age-old mystery surrounding Antonie van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes. A unique collaboration at the interface between culture and science has proved conclusively that the linen trader and amateur scholar from Delft ground and used his own thin lenses.

Considering the unrivaled quality of the microscopic images produced by Van Leeuwenhoek, this was always thought to be practically impossible. The prevailing view was that grinding small lenses of such high quality by hand was simply a bridge too far. A new research method helped to solve the mystery—namely, using a neutron bundle from the TU Delft research reactor. The TU Delft Reactor Institute uses radiation to conduct research on materials, for energy and health care purposes.

The microscopes manufactured by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) featured a single lens and a spike upon which the sample was skewered. The microscopes of Van Leeuwenhoek's contemporaries magnified objects approximately 30 times, but his microscopes were up to 10 times more powerful. How he managed this feat remained a mystery up until now. Was there truth in his claim that he had invented an advanced method of glass-blowing, as he revealed to a group of German nobles in a rare moment of candour in 1711? Or was his precise grinding responsible for the quality of the lens?

Van Leeuwenhoek's claim resulted in widespread speculation. Innumerable suggestions were made, but a conclusive answer remained forthcoming. The 11 Leeuwenhoek microscopes that have stood the test of time, four of which are in the collection of Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, are too valuable to dismantle. "Van Leeuwenhoek clasped his lenses between two metal plates, which he secured with rivets," explains Tiemen Cocquyt, a curator at the museum who was involved with the research. "In light of their rarity and enormous historical value, dismantling the microscopes is not an option. Aside from a tiny hole a half-millimetre wide, there's no way of accessing the lenses. More than 90 percent is out of view. And that is the way it has been for the last 350 years."

Uncharged particles

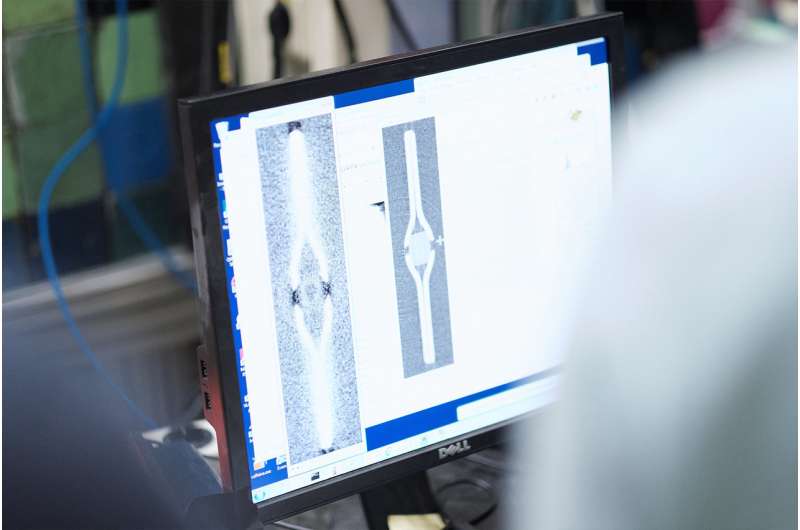

The mystery of the Leeuwenhoek lens was solved thanks to non-invasive neutron tomography, which made it possible to create an image of the inside of the microscope without having to break it open. The Reactor Institute Delft is home to a new instrument that operates using this technology. "Tomography involves rotating an object in a neutron bundle in front of a camera, and photographs are taken as the object rotates," explains Lambert van Eijck, a TU Delft researcher. "Neutrons are uncharged particles and pass through metal – in contrast to X-rays, for example. After you have rotated the object through 180 degrees, you can use the collection of 2-D images to construct a 3-D image of the object on the computer."

A skilled grinder

The resulting image of one of the microscopes from Rijksmuseum Boerhaave leaves no doubt: A Leeuwenhoek microscope does not contain a blown lens, but rather a ground lens. "It would appear that there was no exotic method of production after all, but Van Leeuwenhoek was just exceptionally skilled in grinding tiny lenses," concludes Cocquyt.

The Leeuwenhoek microscope was recently chosen as a Dutch showpiece in the design category on a national television programme. Tiemen Cocquyt says, "The instrument opened new worlds, and Van Leeuwenhoek was the first to view bacteria, sperm cells and blood cells, discoveries that he published in the journal of the British Royal Society." With his simple, yet extremely specialised microscope, Van Leeuwenhoek saw what nobody had seen before – or even could have seen. It was another 150 years before others succeeded in building a microscope capable of revealing more.

A question that the researchers would still like to see answered is whether the lens is made from a special type of glass. "That is something that we can research using gamma spectroscopy," says Van Eijck. "You see, neutron tomography makes objects temporarily radioactive. How the radioactivity decays reveals which elements it contains."

Provided by Delft University of Technology