December 11, 2006 feature

Why a hydrogen economy doesn't make sense

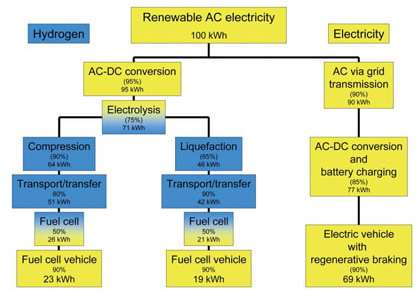

In a recent study, fuel cell expert Ulf Bossel explains that a hydrogen economy is a wasteful economy. The large amount of energy required to isolate hydrogen from natural compounds (water, natural gas, biomass), package the light gas by compression or liquefaction, transfer the energy carrier to the user, plus the energy lost when it is converted to useful electricity with fuel cells, leaves around 25% for practical use — an unacceptable value to run an economy in a sustainable future. Only niche applications like submarines and spacecraft might use hydrogen.

“More energy is needed to isolate hydrogen from natural compounds than can ever be recovered from its use,” Bossel explains to PhysOrg.com. “Therefore, making the new chemical energy carrier form natural gas would not make sense, as it would increase the gas consumption and the emission of CO2. Instead, the dwindling fossil fuel reserves must be replaced by energy from renewable sources.”

While scientists from around the world have been piecing together the technology, Bossel has taken a broader look at how realistic the use of hydrogen for carrying energy would be. His overall energy analysis of a hydrogen economy demonstrates that high energy losses inevitably resulting from the laws of physics mean that a hydrogen economy will never make sense.

“The advantages of hydrogen praised by journalists (non-toxic, burns to water, abundance of hydrogen in the Universe, etc.) are misleading, because the production of hydrogen depends on the availability of energy and water, both of which are increasingly rare and may become political issues, as much as oil and natural gas are today,” says Bossel.

“There is a lot of money in the field now,” he continues. “I think that it was a mistake to start with a ‘Presidential Initiative’ rather with a thorough analysis like this one. Huge sums of money were committed too soon, and now even good scientists prostitute themselves to obtain research money for their students or laboratories—otherwise, they risk being fired. But the laws of physics are eternal and cannot be changed with additional research, venture capital or majority votes.”

Even though many scientists, including Bossel, predict that the technology to establish a hydrogen economy is within reach, its implementation will never make economic sense, Bossel argues.

“In the market place, hydrogen would have to compete with its own source of energy, i.e. with ("green") electricity from the grid,” he says. “For this reason, creating a new energy carrier is a no-win solution. We have to solve an energy problem not an energy carrier problem."

A wasteful process

In his study, Bossel analyzes a variety of methods for synthesizing, storing and delivering hydrogen, since no single method has yet proven superior. To start, hydrogen is not naturally occurring, but must be synthesized.

“Ultimately, hydrogen has to be made from renewable electricity by electrolysis of water in the beginning,” Bossel explains, “and then its energy content is converted back to electricity with fuel cells when it’s recombined with oxygen to water. Separating hydrogen from water by electrolysis requires massive amounts of electrical energy and substantial amounts of water.”

Also, hydrogen is not a source of energy, but only a carrier of energy. As a carrier, it plays a role similar to that of water in a hydraulic heating system or electrons in a copper wire. When delivering hydrogen, whether by truck or pipeline, the energy costs are several times that for established energy carriers like natural gas or gasoline. Even the most efficient fuel cells cannot recover these losses, Bossel found. For comparison, the "wind-to-wheel" efficiency is at least three times greater for electric cars than for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

Another headache is storage. When storing liquid hydrogen, some gas must be allowed to evaporate for safety reasons—meaning that after two weeks, a car would lose half of its fuel, even when not being driven. Also, Bossel found that the output-input efficiency cannot be much above 30%, while advanced batteries have a cycle efficiency of above 80%. In every situation, Bossel found, the energy input outweighs the energy delivered by a factor of three to four.

“About four renewable power plants have to be erected to deliver the output of one plant to stationary or mobile consumers via hydrogen and fuel cells,” he writes. “Three of these plants generate energy to cover the parasitic losses of the hydrogen economy while only one of them is producing useful energy.”

This fact, he shows, cannot be changed with improvements in technology. Rather, the one-quarter efficiency is based on necessary processes of a hydrogen economy and the properties of hydrogen itself, e.g. its low density and extremely low boiling point, which increase the energy cost of compression or liquefaction and the investment costs of storage.

The alternative: An electron economy

Economically, the wasteful hydrogen process translates to electricity from hydrogen and fuel cells costing at least four times as much as electricity from the grid. In fact, electricity would be much more efficiently used if it were sent directly to the appliances instead. If the original electricity could be directly supplied by wires, as much as 90% could be used in applications.

“The two key issues of a secure and sustainable energy future are harvesting energy from renewable sources and finding the highest energy efficiency from source to service,” he says. “Among these possibilities, biomethane [which is already being used to fuel cars in some areas] is an important, but only limited part of the energy equation. Electricity from renewable sources will play the dominant role.”

To Bossel, this means focusing on the establishment of an efficient “electron economy.” In an electron economy, most energy would be distributed with highest efficiency by electricity and the shortest route in an existing infrastructure could be taken. The efficiency of an electron economy is not affected by any wasteful conversions from physical to chemical and from chemical to physical energy. In contrast, a hydrogen economy is based on two such conversions (electrolysis and fuel cells or hydrogen engines).

“An electron economy can offer the shortest, most efficient and most economical way of transporting the sustainable ‘green’ energy to the consumer,” he says. “With the exception of biomass and some solar or geothermal heat, wind, water, solar, geothermal, heat from waste incineration, etc. become available as electricity. Electricity could provide power for cars, comfortable temperature in buildings, heat, light, communication, etc.

“In a sustainable energy future, electricity will become the prime energy carrier. We now have to focus our research on electricity storage, electric cars and the modernization of the existing electricity infrastructure.”

Citation: Bossel, Ulf. “Does a Hydrogen Economy Make Sense?” Proceedings of the IEEE. Vol. 94, No. 10, October 2006.

By Lisa Zyga, Copyright 2006 Physorg.com