Inhibitor for abnormal protein points the way to more selective cancer drugs

Nowhere is the adage "form follows function" more true than in the folded chain of amino acids that makes up a single protein macromolecule. But proteins are very sensitive to errors in their genetic blueprints. One single-letter DNA "misspelling" (called a point mutation) can alter a protein's structure or electric charge distribution enough to render it ineffective or even deleterious.

Unfortunately, cells containing abnormal proteins generally coexist alongside those containing the normal (or "wild") type, and telling them apart requires a high degree of molecular specificity. This is a particular concern in the case of cancer-causing proteins.

"With present technologies, developing a drug that will target only the mutant version of a protein is difficult," notes Blake Farrow, a graduate student in materials science at Caltech and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Fellow. "Most anticancer agents indiscriminately attack both mutant and healthy proteins and tissues."

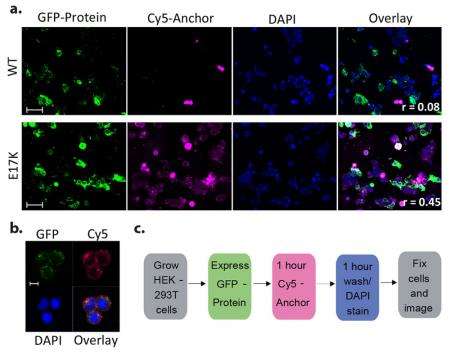

Farrow is part of a Caltech-led team that recently created a new type of highly selective molecule that can actively distinguish a mutated protein from the wild type by binding only the mutated protein.

The work was described in a paper that appeared in Nature Chemistry on April 13.

The project was begun by Kaycie Deyle (PhD '14), now a postdoctoral fellow at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, and utilized a number of novel technologies, including click chemistry and protein-catalyzed capture (PCC). Click chemistry is a technique for rapidly and reliably constructing molecular assemblies from modular components. PCC screening, which was developed by the Caltech researchers, uses click chemistry to reveal which of several candidate molecules will bind (and "click") most strongly to a given region of a specific protein.

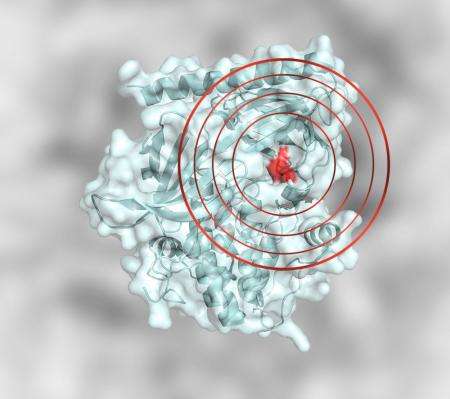

As a test case, the researchers investigated a point mutation called E17K, which occurs in a specific region of Akt1, a protein hundreds of amino acids long. Akt1 plays a key role in cell growth and proliferation, and its E17K mutation is closely linked to an increase in the development of tumors and the survival of cancer cells.

Using a synthesized fragment of the cancer-causing form of Akt1, the researchers replaced an amino acid close to the E17K mutation with a structure that could act as a "click handle." The goal was to create a short molecule that could wedge itself into the folds of the protein, binding to the E17K mutation at one end and "clicking" to the handle at the other.

Candidate molecules were constructed by splicing amino acids together into short chains five amino acids long, which is just enough to reach from the click handle to the mutation site. With almost two dozen amino acids to choose from for each of the five slots, the researchers were faced with over a million possible configurations.

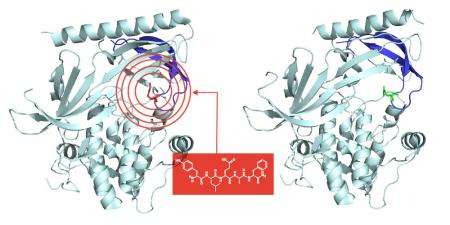

A multistep PCC screening process narrowed this large number of candidates down to one combination that bound to the mutant version of the protein 10 times more strongly than to the wild type. The code letters representing the five amino acids making up the molecule gave it its informal name: "yleaf."

Next, a second PCC screening process was used to find amino acid chains that could be used to extend the yleaf molecule, giving it the ability to grip multiple naturally occurring features of the Akt1 molecule, rather than requiring a click handle to be artificially inserted. Testing of this wider-wingspan yleaf showed that not only did it bind almost exclusively to its intended target (and nowhere else, including the unmutated form of Akt1), but also that in doing so it inhibited the protein's activity and hence could be expected to impair its ability to support tumor growth. In fact, the extended yleaf molecule inhibited the mutated protein a thousand times better than it did the wild-type form.

James Heath, the Elizabeth W. Gilloon Professor and Professor of Chemistry at Caltech and corresponding author of the paper, says this selective inhibitor strategy "is certainly a very important first step" toward new cancer drug modalities. With additional design considerations to facilitate passage through the cell membrane, compounds of this sort could become the basis of new drugs for targeting and inhibiting abnormal protein molecules in living cells, he says.

Journal information: Nature Chemistry

Provided by California Institute of Technology