Female fish genitalia evolve in response to predators, interbreeding

Female fish in the Bahamas have developed ways of showing males that "No means no."

In an example of a co-evolutionary arms race between male and female fish, North Carolina State University researchers show that female mosquitofish have developed differently sized and shaped genital openings in response to the presence of predators and - in a somewhat surprising finding - to block mating attempts by males from different populations.

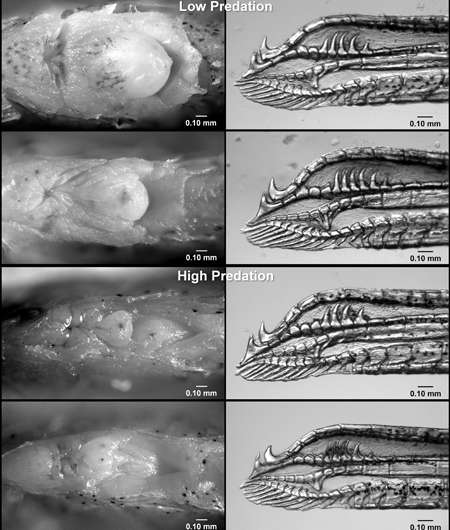

"Genital openings are much smaller in females that live with the threat of predators and are larger and more oval shaped in females living without the threat of predation," said Brian Langerhans, assistant professor of biological sciences at NC State and the corresponding author of a paper published in the journal Evolution that describes the research.

"Our lab previously showed that male mosquitofish have more bony and elongated genitalia when living among predators. When predators lurk nearby, male fish must attempt to copulate more frequently - and more hurriedly - with females. So females have evolved a way to make copulation more difficult for unwanted males."

The study also shows that females have evolved differently shaped genitalia to deter unwanted advances from males of different populations. This "lock and key" theory suggests that females can better choose advances from wanted males by shaping their genitalia to promote copulation with desired males of their own population or species. Female fish, then, can provide the "lock" best suited to a favored male's "key," and consequently avoid hybridization with maladapted populations or other species - think of low-fitness results in nature like the sterile mule.

"We found that populations with greater evidence of interbreeding had more divergently shaped genitalia in both males and females," said Christopher Anderson, the paper's first author and a former graduate student in Langerhans' lab who is now a doctoral student at East Carolina University. "This suggests that genitalia can evolve, at least partly, to reduce hybridization and thus could be involved in the formation of new species, although more experimentation is needed."

More information: Origins of female genital diversity: predation risk and lock-and-key explain rapid divergence during an adaptive radiation, Christopher Anderson and Brian Langerhans, North Carolina State University, online Aug. 10, 2015, in Evolution, DOI: 10.1111/evo.12748

Journal information: Evolution

Provided by North Carolina State University