This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Locusts adapt sense of smell to detect food in swarms, study shows

Locusts adapt their sense of smell to better detect sparse food sources in crowded swarms of up to billion animals, as researchers from the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behavior at the University of Konstanz discovered. They published their results in the journal Nature Communications.

"I couldn't imagine the scale until I saw it with my own eyes," reports Einat Couzin-Fuchs.

When a plague of locusts broke out in Kenya four years ago, she and her team were in the field. She says, "Some areas were just fully infested, with only toxic plants left behind after the locusts had moved through."

Back at their workplace, the University of Konstanz, they planned experiments and models based on the data collected in the field. Their mission: to unravel the mysteries of locust plagues, a global threat that affects one in ten people on the planet.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that a swarm of one billion locusts devours around 1,500 tons of food in a single day, equivalent to the daily food needs of 2,500 people. These staggering figures highlight the urgency and importance of their research.

Substantial differences between solitary and gregarious animals

It is important to note that locusts are not always swarming. Locusts are grasshoppers that can switch between a solitary (living alone) and gregarious (living in a swarm) state within a few hours. This change of state has a large impact on behavior, development, physiology and reproduction. Changes are also exhibited in the nervous system and body color, which changes from camouflage green to a striking yellow-black.

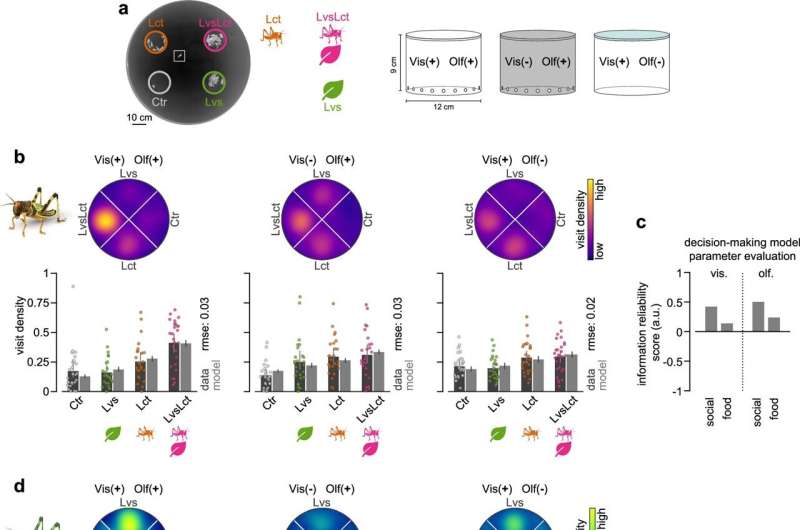

"This extreme change in lifestyle impacts how animals search for food as well as the availability of information animals have at their disposal when foraging," says doctoral student Inga Petelski. Therefore, she conducted behavioral experiments to monitor foraging decisions in the lab by exposing solitary and gregarious animals.

Food choices could be perceived either visually or olfactorily or in combination. Her colleague Yannick Günzel uses the data obtained to develop a decision-making model. "Based on the behavioral experiments and the decision-making model, we found that the sense of smell is extremely important in gregarious animals when searching for food," says the neurobiologist.

Key in the olfactory system of animals

Therefore, the research team knew that a central key lies in the olfactory system. Consequently, they took a closer look at the area of the brain responsible for smell processing using an in vivo calcium imaging technique. This procedure visualizes information processing across entire regions of the brain.

The apparent result: "If you pair food and grasshopper scent, you get a synergistic effect: the brain activity is significantly more pronounced than you would expect from pure addition. We only found this effect in the gregarious grasshopper," says Petelski.

This means that locusts adapt their sense of smell when they switch to the gregarious lifestyle. Their olfactory system now appears to be specialized to better detect food odors in the swarm's odor cocktail.

Her colleague Günzel concludes, "This is the reason why food can still be sensibly perceived by locusts in a swarm."

"Combining calcium imaging experiments and computational analyses, our team has succeeded in gaining a better understanding of how locusts adapt to new environmental conditions," says group leader Couzin-Fuchs. "We now have a better mechanistic understanding of the neural changes happening in the transition to swarming."

She is certain that future research and method development will advance our ability to understand, and therefore predict, and manage future outbreaks.

More information: Inga Petelski et al, Synergistic olfactory processing for social plasticity in desert locusts, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-49719-7

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Konstanz