This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

'Shear sound waves' provide the magic for linking ultrasound and magnetic waves

A team led by researchers from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science in Japan has succeeded in creating a strong coupling between two forms of waves—magnons and phonons—in a thin film. Importantly, they achieved this at room temperature, opening the way for the development of hybrid wave–based devices where information could be stored and manipulated in a variety of ways.

Most computing devices in use today are based on the movement of electric charge—electrons—but there are limits to how fast the electrons can travel, and their movement generates heat, which creates losses in energy and is environmentally undesirable.

In response, scientists are working to develop devices that take advantage of wave-like forms of energy such as sound, light, and spin, as they could potentially lead to the creation of more lossless devices.

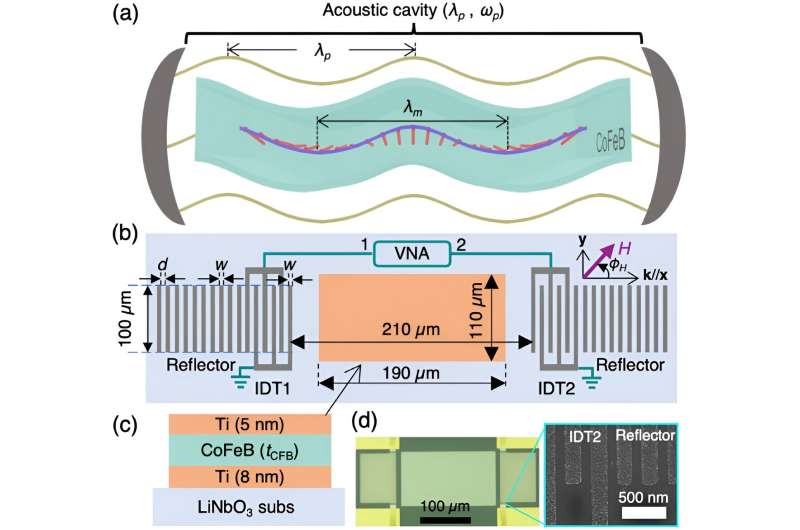

For the current research, published in Physical Review Letters, the scientists looked at two wave-like forms: magnons—quasiparticles that represent the collective excitation of spins, a magnetic property, and phonons—an acoustic phenomenon that in this case was made of surface waves propagating along the film.

According to Yunyoung Hwang, the first author of the study, "Devices using magnons and phonons have been developed, but we, like other researchers, felt that teaming up ultrasound and magnets could lead to big leaps in information and communication technologies. When these two states work together very tightly, it creates a novel hybrid state, and we feel this will open the door for exciting progress in information processing."

Although other groups have tried to do this, there was a snag: regular sound waves on surfaces don't link up well with magnets. The team was able to crack this code by using a different kind of sound waves, called shear sound waves, which are a better match for magnets.

The key element that made the work possible was a small on-chip device called a nano-structured surface acoustic wave resonator. It confines ultrasound waves to a specific spot and enhances shear sound waves, allowing a strong coupling between the surface sound waves and magnets in the resonator. Through this, the researchers were able to achieve strong magnet-sound coupling in a Co20Fe60B20 film, at room temperature.

According to Jorge Puebla, another author of the study, "In particular, we feel that our work will contribute to the study of coherently coupled magnon-phonon quasiparticles, which could help the development of hybrid wave-based information processing devices with relatively small losses.

"Beyond this, two intriguing avenues emerge on the horizon: advancements in our devices could lead us into the ultra-strong coupling regime, a domain yet to be fully explored; alternatively, by conducting similar experiments at ultra-low temperatures, we have the potential to explore quantum phenomena."

More information: Yunyoung Hwang et al, Strongly Coupled Spin Waves and Surface Acoustic Waves at Room Temperature, Physical Review Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.132.056704. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2309.12690

Journal information: Physical Review Letters , arXiv

Provided by RIKEN