This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Scientists show how some of Earth's earliest animals evolved

Lacking bones, brains, and even a complete gut, the body plans of simple animals like sea anemones appear to have little in common with humans and their vertebrate kin. Nevertheless, new research from Investigator Matt Gibson, Ph.D., at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research shows that appearances can be deceiving, and that a common genetic toolkit can be deployed in different ways to drive embryological development to produce very different adult body plans.

It is well established that sea anemones, corals, and their jellyfish relatives shared a common ancestor with humans that plied the Earth's ancient oceans over 600 million years ago. A new study from the Gibson Lab, published in Current Biology, illuminates the genetic basis for body plan development in the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis. This new knowledge paints a vivid picture of how some of the earliest animals on earth progressed from egg to embryo to adult.

"Studying the developmental genetics of Nematostella is sort of like taking a time machine into the very distant past," said Gibson. "Our work allows us to ask what life looked like long ago— hundreds of millions of years before the dinosaurs. How did ancient animals develop from egg to adult, and to what extent have the genetic mechanisms that guide embryonic development endured across millennia?"

Most contemporary animals, from insects to vertebrates, develop by forming a head-to-tail series of segments that assume distinct identities depending on their position. Within a given segment, there is a further axis of polarity that informs cells whether they are at the front or back of the segment. Collectively, this is referred to as segment polarization.

Shuonan He, Ph.D., a former predoctoral researcher from the Gibson Lab, uncovered genes involved during development of the sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis, that guide the formation of segments and others that direct segment polarity programs strikingly similar to organisms higher up the evolutionary tree of life, including humans.

"The significance is that the genetic instructions underlying the construction of extremely different animal body plans, for example, a sea anemone and a human, are incredibly similar," said Gibson. "The genetic logic is largely the same."

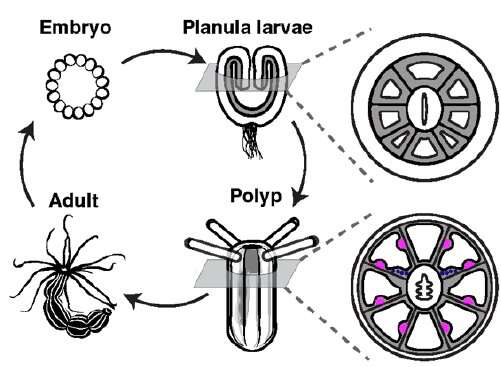

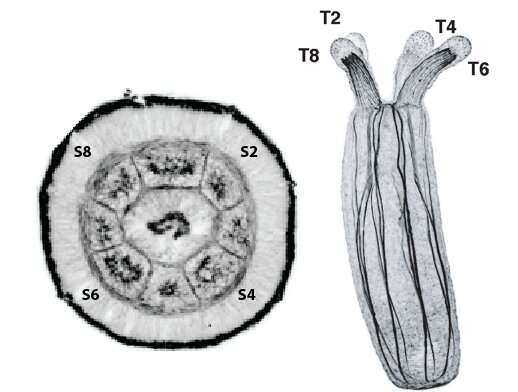

This new study builds upon a 2018 study published in Science from the Gibson Lab that showed that sea anemones have an internal bilateral symmetry early in development with eight radial segments. The study demonstrated that Hox genes—master development genes that are crucial for human development—act to delineate boundaries between segments and likely had an ancient role in segment construction.

-

Schematic illustration of the sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis, life cycle. Retractor muscle cell types (magenta) are patterned within segments. Credit: Stowers Institute for Medical Research -

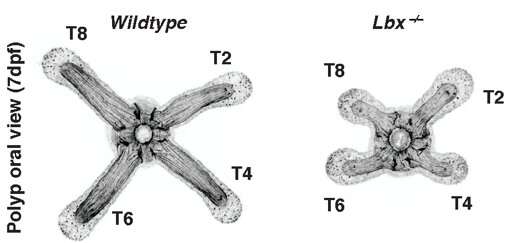

Comparison of morphological difference between a normal seven-day-old sea anemone (left) and a sea anemone lacking a required segment polarity gene (right). Credit: Stowers Institute for Medical Research

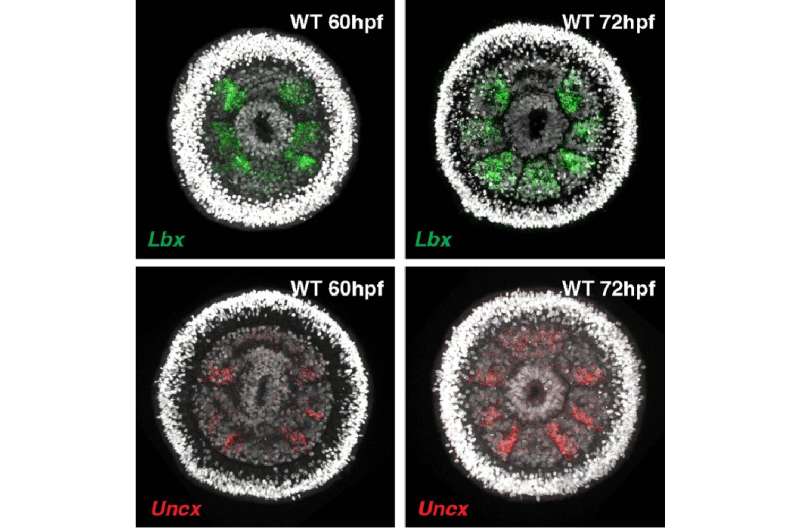

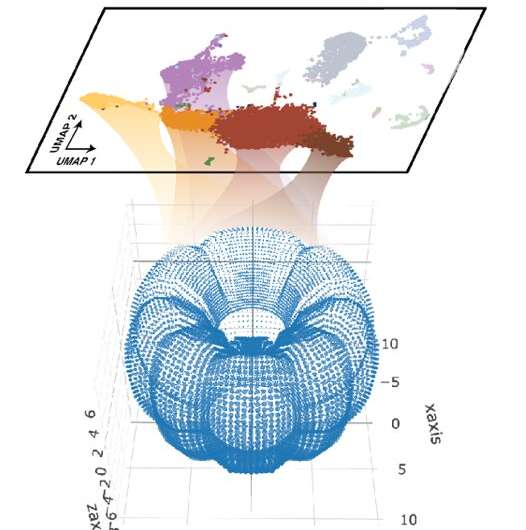

The team's latest finding explores how segments form and what accounts for differences in their identities. Using spatial transcriptomics, or the differences in gene expression between segments, the team discovered hundreds of new segment-specific genes. These include two crucial genes that encode transcription factors that govern segment polarization under the control of Hox genes and are required for the proper placement of sea anemone muscles.

The astonishing diversity of organisms on Earth can be compared to the assembly of Legos. "Whether you construct a dinosaur, a sea anemone, or a human, many of the core genetic building blocks are largely the same despite drastically different animal forms," said Gibson.

This is the first time that scientists have evidence of a molecular basis for segment polarization in a pre-bilaterian animal. While extensively studied in bilateral species like fruit flies and humans, the idea that cnidarian animals possess segmentation was unexpected. Now, the team has evidence that these segments are also polarized.

"This provides further evidence that investigating a broad diversity of animals can have direct implications for understanding general principles, including those which apply to human biology," said Gibson. "Going one step further, by understanding the logic of sea anemone development and comparing it to what we see in vertebrates, we can also extrapolate back in time to understand how animals likely developed hundreds of millions of years ago."

More information: Shuonan He et al, Spatial transcriptomics reveals a cnidarian segment polarity program in Nematostella vectensis, Current Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.044

Journal information: Current Biology , Science

Provided by Stowers Institute for Medical Research