Evolutionary change in protective plant odors help flora evade invasive species over time

Plants can't run away from enemies. Still, they would like to keep life-threatening herbivores at a distance. This can be done with odors. Klaas Vrieling of the Institute of Biology Leiden found out with his team how plants change odor production to keep the munchers at a distance.

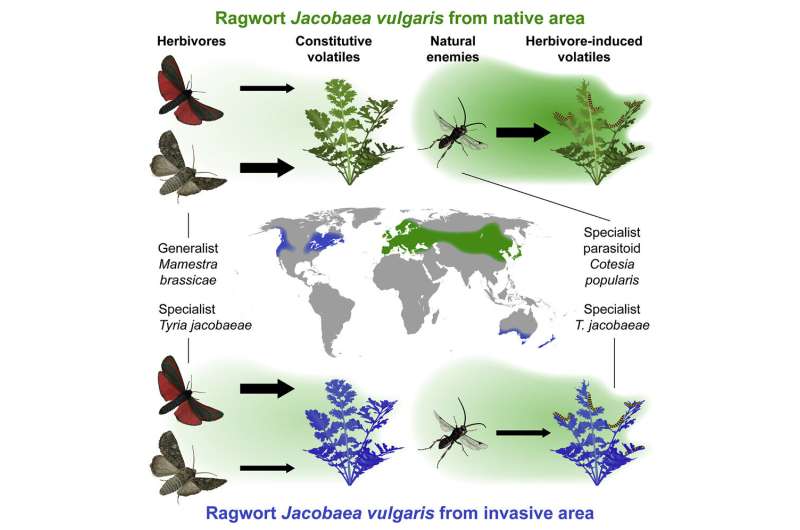

"Common ragwort is native in Europe and Asia, but is now an invasive species on other continents. That is lucky for us, as this invasive version creates an opportunity to test how odor production changes in environments where herbivores pressure is radically different," Vrieling explains.

Contradictory at first glance

The odor production is linked to repelling herbivorous insects. Yet, the team found something that at first glance seems contradictory. "We found that the native plant produced less odor than its invasive relatives," the researcher tells. ' One would expect that odor production is higher in the native range, as over evolutionary time the plant would have accrued a denser herbivore guild."

The eventual cause was found with the cinnabar moth. This species is found in the native range only and it specifically feeds on common ragwort. And the odor which would keep insects at a distance, smells like a delicious meal for this moth.

"This means that the native plant has a dilemma: if it produces too much odor, it attracts the specialist moth. But if it produces too little, all other herbivorous insect attack the plant," Vrieling explains. "This is not the case with the invasive ragwort, as the moth is absent in these ranges and generalist herbivores are present. And as a consequence you see that within some 60 generations, a relatively short time, the quantity of this odor increases twofold on the invasive continents." Indeed the specialist herbivores find the odors of the invasive ragwort more attractive than the odors of native ragwort while the opposite was found for generalist insect herbivores.

Prove for evolution

Even more special, is that this phenomenon happens in all invasive ranges. Independently, the odor has evolved the same way. "That is explicit evidence that for an fast evolutionary change in odor production," Vrieling explains.

Enemies for enemies

Vrieling and his team were also interested in another odor, with which plants can cry for help. "With common ragwort this happens when cinnabar moth caterpillar starts to feed on the plant," Vrieling tells. "Then it produces a specific odor which is attractive to ichneumon wasps. These wasps only lays eggs in the caterpillar of the cinnabar moth and kills them in this way."

The cinnabar moth only occurs in the native area of common ragwort. In the lab of Ted Turlings in Neuchatel in Swiss, we saw that native ragwort produces five times more of this specific odor when fed upon by caterpillars compared to the invasive plant. Additionally, also the ichneumon wasps were more attracted to the specific odor of native ragwort with feeding cinnabar moth larvae than the odor of invasive ragwort with feeding cinnabar moth larvae.

"And even more important, when we brought both native and invasive species together in the field in the native range, we saw that the native ragworts were better protected. Ten days after introducing the same number of larvae on each plant, a more had disappeared from the native plant and more were parasitized by ichneumon wasp. This shows that this odor is very important for protection, but in 60 generations was decreased in invasive ragwort because when the cinnabar moth and its ichneumon wasp became absent. "Odor production of ragwort quickly adapts over evolutionary time," Vrieling concludes about the research.

Opportunity for breeders

Vrieling also thinks these findings may be used in agriculture in the future. "It would be fascinating to see breeders create plants with strong odors with which they defend themselves from their herbivores and at the same time improve the efficacy of biological control agents. It could reduce the use of pesticides to arrive at a more sustainable culture. There lies still some great opportunities."

More information: Tiantian Lin et al, Evolutionary changes in an invasive plant support the defensive role of plant volatiles, Current Biology (2021). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.055

Journal information: Current Biology

Provided by Leiden University