An unlikely marriage among oxides

The term alloy usually refers to a mixture of several metals. However, other materials can also be alloyed. In the semiconductor industry, for instance, oxide and nitride alloys have long been used successfully to tune the material's functional properties. Usually, these changes occur gradually and the properties of the base materials are still easy to recognize.

However, if compounds with unmatched crystal structures are mixed, "heterostructural alloys" are formed. In these alloys, the structure changes depend on the mixing ratio of the components. Sometimes, this yields surprising properties that differ remarkably from those of the base materials. It is these oxide alloys that Empa researcher Sebastian Siol is interested in. He not only wants to discover them, but make them usable for everyday life. In his quest to find the desired material, he has to keep an eye on several materials properties at once, such as the structure, the electronic properties—and the long-term stability.

Siol joined Empa last year. Previously, he conducted research at the National Renewable Energy Research Laboratory (NREL) in Golden, Colorado, where he left behind a notable publication: alloys with "negative pressure." Together with his colleagues, he mixed manganese selenide and manganese telluride using a cold-steam technique (magnetron sputtering). At certain ratios, the base materials merged to form a crystal lattice that was "uncomfortable" for both components. Neither of the partners could force its favorite crystal structure, which it prefers in a pure state, upon the other.

The resulting compromise was a new phase, which normally would only form at "negative pressure"—i.e., when the material is permanently exposed to tension. These materials are extremely difficult to produce under normal conditions. Siol and his colleagues at NREL have managed to overcome this difficulty. The new material, now accessible thanks to this method, displays many useful properties. For instance, it is piezoelectric. In other words, it can be used to generate electricity, produce detectors—or conduct semiconductor experiments, which would not have been possible with the pure base materials.

Researching stable systems

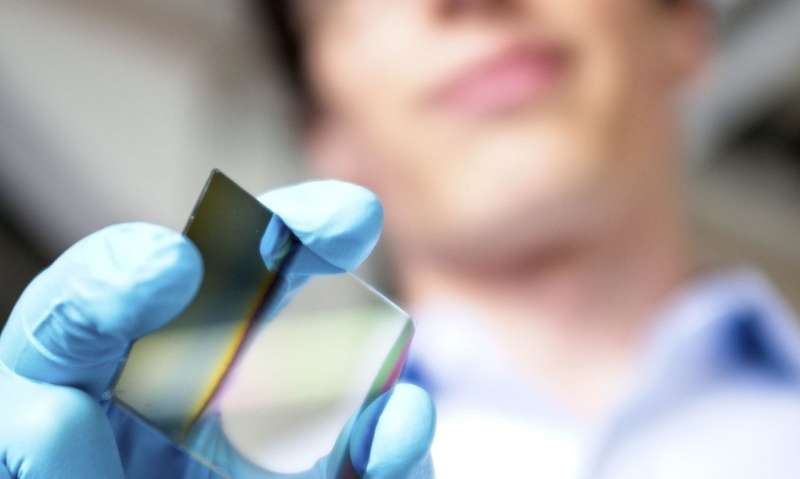

At Empa, Siol will bring his experience in making "impossible" oxide alloys to the table. He aims to discover oxide mixtures with a variable structure and thus stabilize them to such an extent that they become fit for everyday use. The Laboratory for Joining Technologies & Corrosion headed by Lars Jeurgens has plenty of experience in practical applications for stable oxide layers and alloys. The initial focus is on mixed oxides made of titanium and tungsten oxide, which could be of interest for window coatings, semiconductor technology or sensor technology. Siol's colleague Claudia Cancellieri has been researching the electronic properties of oxide interfaces for several years and contributes her expertise to the project.

"The material combination is very exciting," explains Siol. Titanium oxides are extremely stable and used in solar cells, wall paints and toothpaste. Tungsten oxides, on the other hand, are comparatively unstable and are used for smart windows, gas sensors or as catalytic converters in petrochemistry. "In the past, research often focused solely on optimizing material properties," says Siol. "It is crucial, however, that the material can be used for several years in the respective field of application." For instance, this would be important for semiconductor coatings in electrochromic windows, which have to last for decades in aggressive environments, exposed to sunlight and temperature fluctuations. The Empa researchers are seeking this long-term stability.

To produce these oxide phases Siol and his colleagues use different industrially scalable techniques: controlled oxidation of thin metal films in a tube furnace or electrolyte solution, as well as reactive sputtering, where the metals are oxidized directly during the deposition process. "Impossible" oxide alloys, the subject of fundamental research until now, are thus gradually becoming tangible for industrial applications.

More information: Sebastian Siol et al, Negative-pressure polymorphs made by heterostructural alloying, Science Advances (2018). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aaq1442

Journal information: Science Advances