This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

The sun's corona is weirdly hot, and Parker Solar Probe rules out one explanation

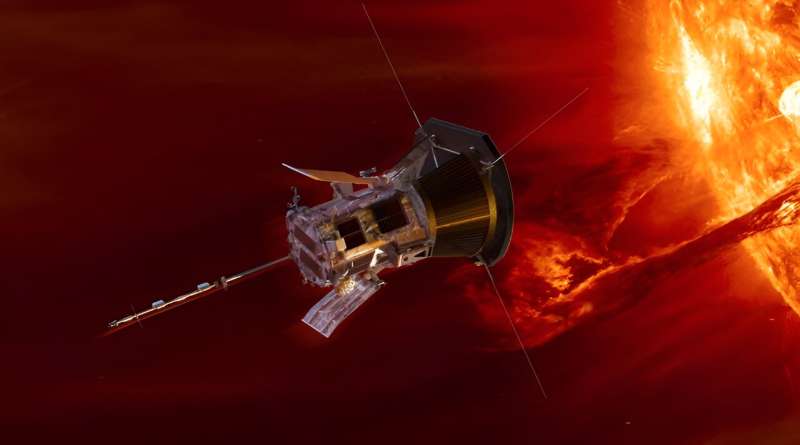

By diving into the sun's corona, NASA's Parker Solar Probe has ruled out S-shaped bends in the sun's magnetic field as a cause of the corona's searing temperatures, according to University of Michigan research published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The sun's crown-like atmosphere can be 200 times hotter than the sun's surface, despite being farther away from the ultimate source of heat at the sun's core. How the corona's heat seemingly defies physics has stumped scientists for decades, yet it allows the sun's hot soup of charged particles, or plasma, to move fast enough to escape the sun's gravitational pull and engulf our solar system as the solar wind.

To solve the mystery, NASA built the Parker Solar Probe to dive into the corona and find its heat source. The spacecraft is equipped with a set of instruments designed by Justin Kasper, U-M professor of climate and space sciences and engineering, to directly measure the density, temperature and flow of the corona's plasma.

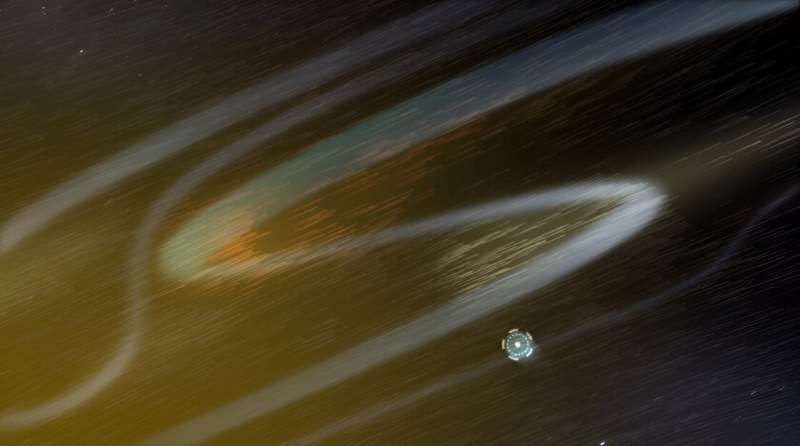

When it first approached the sun, the probe detected hundreds of S-shaped bends in the sun's magnetic field—named switchbacks in reference to how they briefly reverse the direction of the magnetic field—along with thousands of shallower bends. To some scientists, the switchbacks seemed like promising sources of heat to the corona and solar wind. Their severe S-shape bend stored a lot of magnetic energy, which likely released into the surrounding plasma as the switchbacks traveled through space and eventually straightened out.

"That energy has to go somewhere, and it could be contributing to heating the corona and accelerating the solar wind," said Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti, U-M assistant research scientist of climate and space sciences and engineering and the corresponding author of the study.

But to heat the corona, switchbacks need to move through it, so learning where switchbacks form is critical for understanding their influence on the corona's temperature. After poring over the data from the Parker Solar Probe's first 14 laps around the sun, the research team discovered that while the S-shaped bends are common in the solar wind near the sun, they are absent inside the corona.

Scientists still can't agree on what causes switchbacks. Some think that the magnetic field is bent by turbulence in the solar wind beyond the corona. Others think that switchbacks start their journey at the surface of the sun, when churning magnetic field lines and loops explosively collide and combine into bent shapes.

The study's results rule out the latter hypothesis. If switchbacks were formed by colliding magnetic fields at the surface of the sun, they ought to be even more common inside the corona. However, Akhavan-Tafti thinks magnetic collisions could still play some indirect role in the origins of switchbacks—and the heating of the corona.

"Our theory could fill the gap between the two schools of thought on S-shaped switchback generation mechanisms," Akhavan-Tafti said. "While they must be formed outside the corona, there could be a trigger mechanism inside the corona that causes switchbacks to form in the solar wind."

When magnetic fields collide on the sun's surface, they vibrate like plucked guitar strings and send waves along the magnetic fields into space. At the same time, the energy from the collisions creates very fast streams of plasma in the solar wind.

Akhavan-Tafti thinks the fast plasma distorts the magnetic waves into switchbacks in the solar wind. If some of those waves dissipate inside the solar atmosphere before becoming switchbacks, they could also play a part in heating the corona.

"The mechanisms that cause the formation of switchbacks, and the switchbacks themselves, could heat both the corona and the solar wind," he said.

There currently isn't enough data to favor triggers at the sun's surface over turbulence in the solar wind as the cause of switchbacks, however.

"Parker Solar Probe's upcoming trips into the sun, as early as December 24, 2024, will collect more data even closer to the sun. We will use the data to further test our hypothesis," Akhavan-Tafti said.

More information: M. Akhavan-Tafti et al, In Situ Mechanisms are Necessary for Switchback Formation, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2024). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ad60bc

Journal information: Astrophysical Journal Letters

Provided by University of Michigan