Making a good thing better: An acid test that won't drown in water

Near-infrared cyanine dyes are go-to tools for studying the inner workings of cells and investigating the biochemistry of disease, including cancer.

But even though they have low toxicity and plenty of applications, these fluorescent dyes have a weakness, says Haiying Liu, a professor of chemistry at Michigan Technological University. Put the dyes in water and they quit working. Their molecules clump together, or aggregate, which significantly reduces their brightness.

Liu and his team wondered if it had to be that way. "We thought it might be possible to use aggregation to turn on the dye's fluorescence," he says. "We wanted to turn a drawback into an advantage."

So they built a new cyanine dye that works in water and has other beneficial properties. Their research was published recently in Chemical Communications.

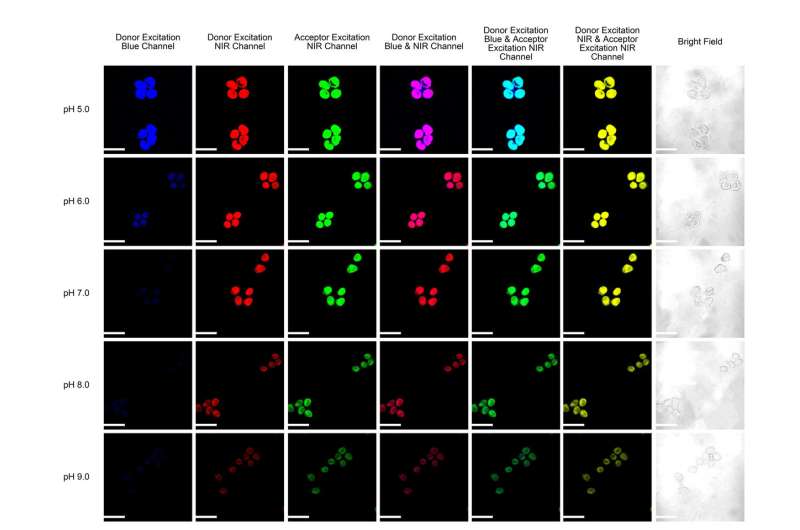

Liu began by attaching the chemical tetraphenylethene (TPE) to a conventional cyanine dye that measures pH. The new dye does what the conventional dye does not: it fluoresces when it aggregates in water, glowing brightly when conditions are acidic and fading in alkaline conditions. Plus, the new dye has an additional advantage since it fluoresces under both near-infrared light and visible light.

"Near-infrared is useful in biomedical research because it penetrates deep tissue," Liu says. Plus, this dual fluorescence gives scientists more bang for their buck. "We can determine the pH change in two different colors, which lets us double check the imaging results."

The researchers tested their cyanine dye on living cells grown in watery solutions of varying pH. They found that cells incubated in acidic solutions fluoresced, while the fluorescence faded in cells grown in alkaline conditions.

The team also wanted to see if the dye could track pH fluctuations in cells exposed to oxidative stress-a marker for a disease, including cancer. Under these conditions, pH levels within the cells tend to drop.

So the researchers also tested two cell cultures. The first had been incubated with an oxidant, hydrogen peroxide; the second with the chemical N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) that turns off a protective antioxidant in cells. In both cases, the cells fluoresced more brightly after they were incubated, demonstrating that their pH had dropped into the acid range.

The new fluorescent dye is relatively simple to make in the lab, Liu explains, and it could definitely help researchers who need to detect cellular pH in solutions with a high percentage of water. In addition, he believes the technique could be adapted to different types of cyanine dyes.

"By modifying the hydroxyl groups from TPE donor," he says, "you could develop new dyes for sensing and imaging carbon dioxide, enzymes and biothiols like GSH."

More information: Mingxi Fang et al, A cyanine-based fluorescent cassette with aggregation-induced emission for sensitive detection of pH changes in live cells, Chemical Communications (2018). DOI: 10.1039/C7CC08986D

Journal information: Chemical Communications

Provided by Michigan Technological University