Chemists Discover How Cells Create Stability During Critical DNA-to-RNA Information Transfers

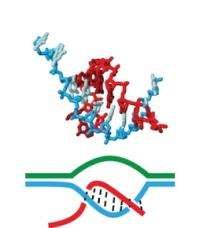

(PhysOrg.com) -- A pair of University of Massachusetts Amherst chemists believe they have for the first time explained how the main players in transcription -- RNA polymerase, RNA (red in illustration) and the DNA template (blue) -- come together and link tightly enough to create a stable complex while DNA unwinds to pass crucial genetic information to RNA, but not so tightly that they can't come apart easily once transcription is complete. This transcription process takes place in all cells and is essential for making the proteins that carry out almost every process important to life.

Many scientists thought this particular phase of transcription, known as elongation, must rely primarily on base pairing, but UMass Amherst’s Craig Martin and graduate student Xiaoqing Liu say reality is more complicated than once believed. Specifically, they say the old one-dimensional “train track” model of the DNA-RNA interaction can now be replaced with a more elegant one. In it, a flexible thread of RNA winds around the ladder-like DNA strand, creating a loop that locks them together as RNA polymerase makes RNA from the DNA template. They call this looped tether a “topological lock.”

Martin says, “Our finding will be fairly surprising to many people. But I think it is a reminder that we need to be thinking in three dimensions when modeling RNA-DNA interactions. What we’ve discovered is that genes exist in a three-dimensional helix for a number of very good reasons and the topological lock depends on this three-dimensional relationship for its success.” Their findings appear in the current issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Elongation involves RNA polymerase, an enzyme that makes RNA by first positioning itself next to DNA genes, then the DNA template it uses to form RNA, from which proteins are synthesized. During the first stage, as Martin describes, a “transcription bubble” forms as a result of separating the two halves of the DNA like opening a zipper. A fully functional elongation complex contains both an eight-base-pair bubble and an 8-base-pair DNA-RNA duplex.

Why an eight base pair duplex is usually involved, and not four or 12, has usually been explained, he adds, by assuming that eight is the minimum number of base pairs able to confer the required stability, but this has never been fully explored.

However, with this new understanding of the topological lock, in which RNA polymerase loops around and through the DNA template, it seems more clear why eight base pairs is optimal, Martin notes. As he explains, “eight is the minimum length required to achieve a topological lock, but more than that would interfere with release of the RNA at the proper time, the end of a gene. So there’s no reason for the connection to be super stable at 20 base pairs, for example. That would be unwieldy.”

Investigation will continue in Martin’s laboratory on transcription in general and on the role of RNA polymerase in the proper regulation of RNA synthesis, including the starting or promoter sequences and termination message that ends it.

Martin is the designer a three-dimensional, interactive display of biologically significant molecules called the Molecular Playground, located in the lobby of the new Integrated Sciences Building on the UMass Amherst campus. Images projected on a 6x9-foot wall show the 3-D structure of chemicals and familiar molecules compounds such as hemoglobin, glucose, vitamin D, insulin, caffeine and a variety of drugs in a way that feels as much like art as possible, he says, while remaining true to the underlying chemistry, so people can develop an appreciation for their fascinating structures. Observers can push, rotate and resize the molecular image at will.

Provided by University of Massachusetts Amherst