Gigapixel camera that takes high-resolution snapshots of entire body could be simple new tool for cancer screening

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer type in the United States, and it's also the deadliest form of skin cancer, causing more than 75 percent of skin-cancer deaths. If caught early enough though, it is almost always curable. Now a camera, capable of taking snapshots of the entire human body and rendering high-resolution images of a patient's skin may help doctors spot cancer early and save lives.

Developed by a team of researchers at Duke University in North Carolina, USA, the "gigapixel whole-body photographic camera" is essentially three dozen cameras in one, allowing the researchers to image the entire body down to a freckle. The research will be presented at The Optical Society's (OSA) 98th Annual Meeting, Frontiers in Optics, being held Oct. 19-23 in Tucson, Arizona, USA.

"The camera is designed to find lesions potentially indicating skin cancers on patients at an earlier stage than current skin examination techniques," said Daniel Marks, one of the co-authors on the paper. "Normally a dermatologist examines either a small region of the skin at high resolution or a large region at low resolution, but a gigapixel image doesn't require a compromise between the two."

Although whole-body photography has already been used to identify melanomas and exclude non-dangerous "stable" lesions, the approach is typically limited by the resolution of the cameras used. A commercial camera with a wide-angle lens can easily capture an image of a person's entire body, but it lacks the resolution needed for a dermatologist to zoom in on one tiny spot. So dermatologists typically examine suspicious lesions with digital dermatoscopy, a technique to evaluate the colors and microstructures of suspicious skins not visible to the naked eyes. The need for two types of images drives up costs and limits possibilities for telemedicine.

The gigapixel camera developed by the Duke University team solves this problem by essentially combining 34 microcameras into one. With a structure similar to a telescope and its eyepieces, the camera combines a precise but simple objective lens that produces an imperfect image with known irregularities. The 34 microcameras are arranged in a "dome" to correct these aberrations and form a continuous image of the scene. The exposure time and focus for each microcamera can be adjusted independently, and a computer can do a preliminary examination of the images to determine if any areas require future attention by the specialists.

Marks pointed out that although the resolution of the gigapixel camera is not as high as the best dermatoscope, it is significantly better than normal photography, allows for a larger imaging area than a dermatoscope and could be used for telemedicine, which could make the routine screening available to a larger number of people, even in remote locations.

The gigapixel imaging technology is based on the multiscale camera design, which is part of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency program "Advanced Wide Field-of-View Architectures for Image Reconstruction and Exploitation."

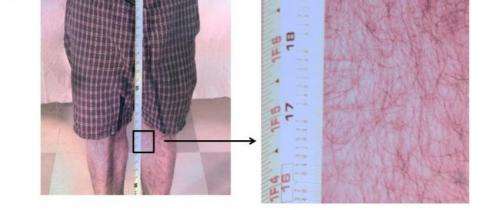

Though the camera will still have to prove effective in clinical trials before becoming routinely available to patients, the researchers have gathered enough preliminary data on a healthy volunteer to demonstrate that it has adequate resolution and the field of view needed for skin disease screening. The next step, they say, is to test how well it works in the clinic.

More information: Presentation FTu2F.5 "Gigapixel Whole-Body Microphotography," takes place Tuesday, Oct. 21 at 11:30 a.m. MST at the Tucson Ballroom, Salon A at the JW Marriott Tucson Starr Pass Resort.

Provided by Optical Society of America