Nano-cone textures generate extremely 'robust' water-repellent surfaces

When it comes to designing extremely water-repellent surfaces, shape and size matter. That's the finding of a group of scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, who investigated the effects of differently shaped, nanoscale textures on a material's ability to force water droplets to roll off without wetting its surface. These findings and the methods used to fabricate such materials-published online October 21, 2013, in Advanced Materials-are highly relevant for a broad range of applications where water-resistance is important, including power generation and transportation.

"The idea that microscopic textures can impart a material with water-repellent properties has its origins in nature," explained Brookhaven physicist and lead author Antonio Checco. "For example, the leaves of lotus plants and some insects' exoskeletons have tiny-scale texturing designed to repel water by trapping air. This property, called 'superhydrophobicity' (or super-water-hating), enables water droplets to easily roll off, carrying dirt particles along with them."

Mimicking this self-cleaning mechanism of nature is relevant for a wide range of applications, such as non-fouling, anti-icing, and antibacterial coatings. However, engineered superhydrophobic surfaces often fail under conditions involving high temperature, pressure, and humidity-such as automotive and aircraft windshields and steam turbine power generators-when the air trapped in the texture can be prone to escape. So scientists have been looking for schemes to improve the robustness of these surfaces by delaying or preventing air escape.

Creating nanoscale textures

"In principle, the high robustness required for several applications could be achieved with texture features as small as 10 nanometers (billionths of a meter) because the pressure needed for liquid to infiltrate the texture and force the air out increases dramatically with shrinking texture size," explained Checco. "But in practice, it is difficult to shrink the surface texture features while maintaining control over their shape."

"For this work, we have developed a fabrication approach based on self assembly of nanostructures, which lets us precisely control the surface texture geometry over as large an area as we want-in principle, even as large as square meters," Checco said.

The procedure for creating these superhydrophobic nanostructured surfaces, developed in collaboration with scientists at Brookhaven's Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), takes advantage of the tendency of "block copolymer" materials to spontaneously self-organize through a mechanism known as microphase separation. The self-assembly process results in polymer thin films with highly uniform, tunable dimensions of 20 nanometers or smaller. The team used these nanostructured polymer films as templates for creating nanotextured surfaces by combining with thin-film processing methods more commonly used in fabricating electronic devices, for example by selectively etching away parts of the surface to create textured designs.

"This new approach leverages our thin-film processing methods, in order to precisely tailor the surface nanotexture geometry through control of processing conditions," said Brookhaven physicist and co-author Charles Black.

The effect of shape

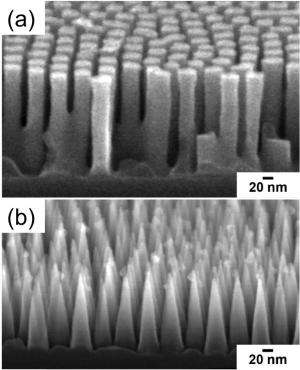

The scientists created and tested new materials with different nanoscale textures-some decorated with tiny straight-sided cylindrical pillars and some with angle-sided cones. They were also able to control the spacing between these nanoscale features to achieve robust water repellency.

After coating their test materials with a thin film of wax-like material, the scientists measured how water droplets rolled off each surface as they were tilted from vertical to flat positions and compared the behavior with that of untextured solids.

"While we fabricated several different nanotextures that all significantly increased the water repellency, certain shapes performed differently than others," said Brookhaven physicist and co-author Atikur Rahman. The enhanced water-repellency was consistent with earlier studies, including a previous one by Checco and collaborators that showed that air bubbles trapped in the textured surfaces force the water to ball up into drops. However, in the current study, the team further showed that cone-shaped nanostructures are significantly better than cylindrical pillars at forcing water droplets to roll off the surface, thus keeping surfaces dry.

"In the case of the cylindrical pillars, as the contact line of the droplet recedes on the textured surface, it can get pinned to the nanotexture, leaving behind a microscopic liquid layer on the pillars' flat tops instead of a perfectly dry substrate," Checco said. "The cone-shaped structures have smaller, pointed tops, likely preventing this effect."

The other important finding was that the water-repelling ability of cone-shaped nanotexturing held up even when water droplets were sprayed onto the surface with a pressurizing syringe. Such pressure could potentially force water into the nanosized pockmarks between the conical or cylindrical pillars, displacing the air bubbles and destroying the water-repelling effect.

The scientists monitored the splashing droplets using a high-speed camera capable of capturing 30,000 frames per second. For the cone-textured surface, "The sprayed droplets splash and eject satellite droplets that spread radially outward while the centermost portion of the original drop flattens out, then recoils, and bounces off the surface," Checco said. "We do not observe any pinned drops at the impact point after the drop has bounced back, indicating that the surface remains water-repellent during the impact at speeds up to 10 meters per second, which is faster than the speed of a falling raindrop."

Next steps

The team is working on extending this technique to other materials, including glass and plastics, and on fabricating surfaces that are also oil-repellent by further tweaking the feature shape.

They are also studying the resistance of different nanotextures to water penetration using intense beams of x-rays available at Brookhaven's National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS). "The goal is to understand quantitatively how the forced liquid infiltration depends on the texture size and geometry. This will assist the design of even more resilient superhydrophobic coatings," Checco said.

The nanopatterning technique used in this study also enables the design of a wide variety of materials with different texturing-and therefore different water-repelling properties-on different parts of a single surface. This approach could be used, for example, to fabricate nanoscale channels with self-cleaning and low fluid friction properties for diagnostic applications such sensing the presence of DNA, proteins, or biotoxins.

"This result is an excellent example of the type of project that can be done collaboratively with the DOE's Nanoscale Science Research Centers," said Black. "Previously, we have been pursuing similar structures for an entirely different scientific purpose. We are happy to work with Antonio through the CFN User program to help him accomplish his research goals."

More information: Paper: dx.doi.org/10.1002/adma.201304006

Journal information: Advanced Materials

Provided by Brookhaven National Laboratory