This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

New model describes synchronized cilia movement driven by border regions

What do the crowd at a football stadium, the feet of a centipede, and the inside of your lungs have in common? All of these systems show the same specific kind of organization, as recently discovered by a group of scientists from MPI-DS.

The crowd wave in a stadium looks like a pattern traveling across the tiers. Similarly, the legs of a centipede move in canon with illusory waves sweeping along its entire length. On a microscopic level, tiny hairs in our lungs called cilia wave together to transport mucus. This serves as a first line of defense against invading pathogens.

Unequal interactions between cilia cause synchronization

To create a synchronized and efficient wave, cilia need to accurately coordinate their beating motion. Unlike football fans watching their neighbors and the nervous system coordinating the centipede's legs, cilia have no such intelligent control system.

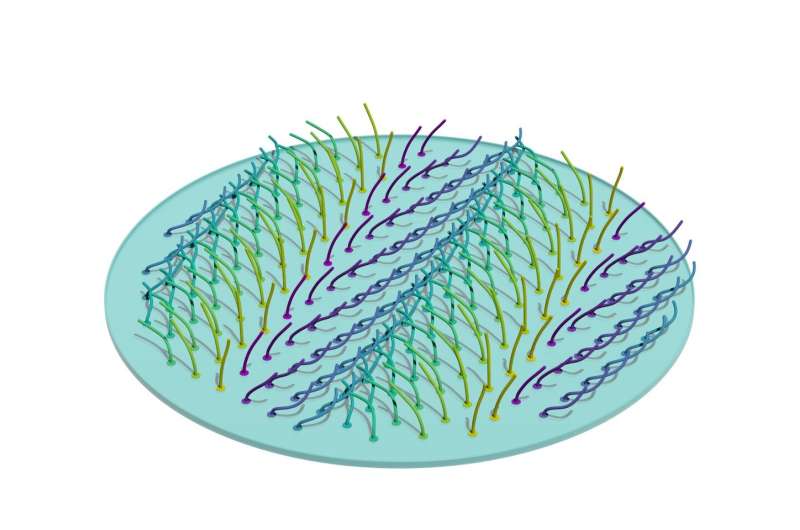

In their new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the scientists David Hickey, Ramin Golestanian and Andrej Vilfan from the department Living Matter Physics at MPI-DS highlight the importance of border regions for the coordination of cilia. "When many cilia beat closely together, they can synchronize by beating slightly before their neighbors to one side, and slightly after their neighbors to the other—just like a wave in a stadium," says Hickey, first author of the study.

This synchronization is mediated by the fluid surrounding the cilia and initiated by the border region. Notably, two cilia beating near each other don't necessarily exert the same force to each other. Depending on its position, a cilium can be more effected by its neighbor than vice versa, especially in a dense carpet of cilia as it frequently occurs in nature. This can eventually cause a directed, non-reciprocal pattern forming a wave.

Synchronization of cilia is initiated by border regions

"The cilia at a border region take the role as a pacemaker which entrain other cilia one after another," Hickey summarizes. "This observation is different from previous models where boundaries were assumed to perturb the order," he continues. This view was also shared by renowned physicist Wolfgang Pauli who joked, "God made solids, but surfaces were the work of the devil."

As found now, border regions of surfaces can in fact allow a better understanding of the self-organization of living matter. At the same time, the model reveals striking similarities between mechanisms in the microscopic world and on the macroscopic scale.

More information: David J. Hickey et al, Nonreciprocal interactions give rise to fast cilium synchronization in finite systems, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2307279120

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Max Planck Society