This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Students admitted to a Brazilian university via affirmative action struggled but ultimately caught up

Affirmative action in higher education can lead to mismatching, with students admitted under such policies struggling academically due to inadequate precollegiate preparation. But although some students face initial challenges, providing access to high-quality education for talented individuals who might otherwise be overlooked due to systemic disadvantages can help students bridge the gap and catch up to their peers.

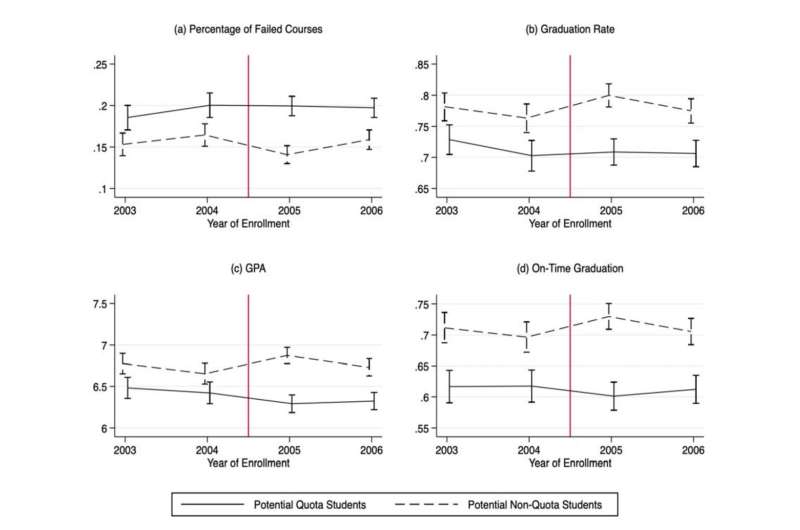

In a new study, researchers examined the effects of a quota-type affirmative action policy at a Brazilian university on gaps in college outcomes between potential beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries. Potential beneficiaries of the policy were less likely to progress smoothly through college and less likely to graduate than their peers who were not admitted under the policy. However, most of the differences between the two groups shrank as students progressed through college, suggesting a catch-up effect.

The study was conducted by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), the United Nations University—World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), and the Sao Paulo School of Economics. It was published as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

"Affirmative action programs have long been a subject of intense debate, with critics saying that they create a mismatch between minority students and the institutions they attend because students admitted under lower standards struggle to keep up academically," notes Edson Severnini, associate professor of economics and public policy at CMU's Heinz College, who coauthored the study. "While previous research has focused on the effects of mismatching, it has overlooked the potential catch-up effects associated with affirmative action programs."

In this study, researchers examined administrative data from the Federal University of Bahia, the largest and best university in the state of Bahia, Brazil, which implemented affirmative action in 2005. Under the policy, 45% of available slots are reserved for former public school students, usually those from low-income households; of the reserved slots, 85% must be filled by Black and mixed-race students. The study ran from 2003 to 2006, two years before and two years after the policy was implemented, and included nearly 7,000 students.

To examine the effects of affirmative action on mismatching and the mechanisms of adjustment, the study considered a variety of variables of students admitted under affirmative action compared to students not admitted under the policy. These included students' entry exam scores, majors, credit hours, grade point averages (GPAs), dropout rates, graduation rates, and ability to catch up (measured by GPA in the first year and final year of college for students who eventually graduated). The study also considered students' socioeconomic status.

The university's affirmative action policy succeeded in targeting disadvantaged students, with the institution's share of quota students after the policy at 43%, close to the 45% target. The share of former public high school students increased even more, from 28% to about 49%.

Potential quota students were 3.91 percentage points more likely to fail and 5.77 percentage points less likely to graduate than non-quota students. They also obtained lower GPAs in the initial years of college, but the gap declined 50% by the time they graduated, suggesting some catching up throughout the college years.

Controlling for entry exam score, the effects on failures and graduation rates disappeared. In addition, the effect on GPA turned positive, suggesting that quota students with entry scores similar to non-quota students performed better while in college.

The negative effects on graduation rates seemed to be driven by students enrolled in technology majors (engineering, computer science, and math-related courses), which require deeper background and skills in math and science. In contrast, the negative effect on GPA and the catching up over time appeared to happen for students enrolled in all three broad fields of study (social sciences, health sciences, and technology).

In addition, potential quota students failed more courses in their first years in college, lowering their GPA in comparison to potential non-quota students. This trend appeared to continue until the fifth college semester. They also reduced the number of credit hours in their first and second college years, probably to focus on fewer courses and improve their learning.

Because the study found no difference in time taken to graduate conditional on not dropping out, this means that potential quota students tended to successfully take more courses and credit hours than potential non-quota students in their last years in college.

"Because our study looked at a setting in which switching majors was costly and the curriculum was rigid, we showed that potential quota students used other mechanisms of adjustment to ultimately graduate in their originally intended major," says Rodrigo Oliveira, research associate at UNU-WIDER, who coauthored the study. "Affirmative action improves social mobility via access to more prestigious colleges and lucrative majors, so it is important to recognize that students admitted under this policy can manage the rigidity of the curriculum."

"This university's affirmative action policy serves as a gateway for students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds to access a prestigious university and acquire a top-tier education," adds Alei Santos, a Ph.D. student at the Sao Paulo School of Economics, who coauthored the study as well. "It also seems to boost diversity in higher education and may play a pivotal role in promoting diversity in the labor market."

More information: Rodrigo Oliveira et al, Bridging the Gap: Mismatch Effects and Catch-Up Dynamics in a Brazilian College Affirmative Action, National Bureau of Economic Research (2023). DOI: 10.3386/w31403 www.nber.org/papers/w31403

Provided by Carnegie Mellon University's Heinz College