This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Cracking the code for better barley, and more of it

Researchers have for the first time identified several genes in barley that could eventually lead to larger yielding crops.

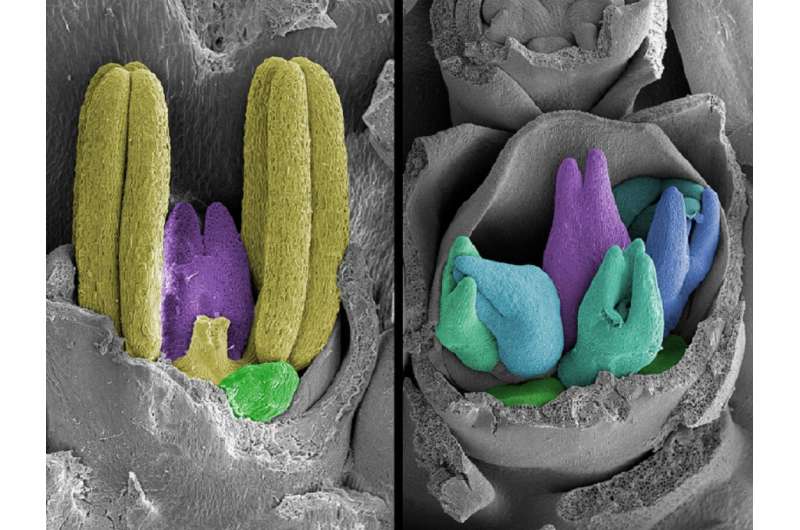

The research was carried out at the University of Adelaide's Waite Research Institute and involved using genetic techniques and molecular biology to examine several historical multiovary barley mutants, and determine which genes boost fertility and make the plants more receptive to cross-pollination.

"Although the mutant varieties appeared to be quite similar when grown in the glasshouse, we found one type was more fertile than the others and was capable of producing up to three times the number of seeds than the other plants," said lead researcher Dr. Caterina Selva, who carried out the work as part of her Ph.D. studies in the University of Adelaide's School of Agriculture, Food and Wine

"The genes in that mutant variety of barley could hold the key to increasing the yield of cereal crops."

The multiovary barley mutants have remarkable features compared to typical Australian barley varieties, producing extra female reproductive organs in each single flower. They were discovered in the 1980s, but this is the first time that the genes responsible for increasing fertility have been identified.

Dr. Selva believes these sequences obtained from the mutant varieties could be used to modify the flower structure of conventional barley, making it more receptive to hybrid breeding.

"By mixing the mutant with other varieties of barley, we can create stronger, more resilient crops that produce higher yields in even the most challenging of environments," she said.

This breeding process, known as hybrid vigor, is already used successfully in maize and rice.

It relies on cross-pollination, which is challenging for wheat and barley due to the structure of the flower.

"This research is an example of how changing one gene can have a positive effect on grain yields. We can overcome barriers to cross pollination by using the more fertile, mutated plants to produce stronger barley and more of it," said senior author Associate Professor Matthew Tucker from the University of Adelaide's School of Agriculture, Food and Wine.

"This is even more important in the face of rapid urbanization, volatile international markets, and extreme weather conditions, which are making growing barley more challenging," he said.

Australia produces just over nine million metric tons of barley each year, the majority of which is exported to Asia.

It is one of the nation's most widely grown crops and covers around 4 million hectares of land from southern Queensland through to Western Australia.

The research was published in the Journal of Experimental Botany and could be used to help improve the agricultural industry both nationally and on a global scale.

"These findings are a promising step towards facilitating hybrid breeding in wheat and barley and ultimately increasing grain yield," said Dr. Selva.

"It could pave the way for enhanced food security and a more sustainable agricultural future."

More information: Caterina Selva et al, HvSL1 and HvMADS16 promote stamen identity to restrict multiple ovary formation in barley, Journal of Experimental Botany (2023). DOI: 10.1093/jxb/erad218

Journal information: Journal of Experimental Botany,

Provided by University of Adelaide