Perhaps a supervoid doesn't explain the mysterious CMB cold spot

For years, cosmologists had thought that a strange feature appearing in the microwave sky, known as the CMB cold spot, was due to the light passing through a giant supervoid. But new research casts that conclusion into doubt.

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the single greatest source of light in all the universe. It completely permeates all of space and is made of light leftover from when the cosmos was only 380,000 years old. At that time, our universe had expanded and cooled to the point that it could transition from a hot, dense plasma into a slightly cooler, but neutral, gas. That process released white-hot radiation with a temperature of around 10,000 K. In the intervening 13.8 billion years, however, that radiation has cooled and redshifted down to around three degrees above absolute zero, which puts that radiation firmly in the microwave regime.

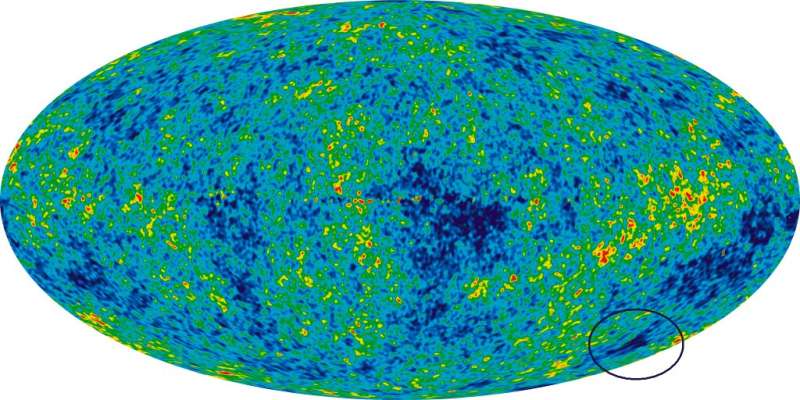

Within that light there are tiny bumps, wiggles and variations in brightness. These variations spread across the sky and are incredibly tiny, with differences no bigger than one part in 100,000. These variations represent tiny density differences in the early universe that would eventually grow up to become galaxies and clusters. Cosmologists understand the statistical properties of these bumps and wiggles to a great degree, but there is one significant outlier known as the cold spot.

The cold spot is about 10° across, and while it is not exceptionally cold, the combination of its lower temperature and its enormous size puts it outside of what we'd expect from our standard model of cosmology.

One plausible hypothesis to explain the cold spot is that the light in that direction of the cosmic microwave background has traveled through a very large patch of the universe that is less dense than average, something called a supervoid.

Because the supervoid is so large, it takes an enormous amount of time for light to cross it. And during that time the void itself grows larger and deeper as the universe evolves. That means that when the light entered the supervoid, the void was smaller than when the light exited. This difference saps energy from the radiation, causing it to cool and redshift more than the average for the rest of the CMB.

Galaxy surveys have shown the potential presence of a supervoid in the direction of the cold spot. But a new study shows that the known supervoids in that direction can only explain a fraction of the size and temperature of the cold spot. Indeed, the new analysis shows that there cannot be a large enough supervoid in that direction, even one hidden behind the limits of our current observational capabilities.

The new research, published on the preprint server arXiv, does not propose a solution to the cold spot mystery, but it does tell us that we have a lot more to learn.

More information: Stephen Owusu et al, The CMB cold spot under the lens: ruling out a supervoid interpretation, arXiv (2022). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2211.16139

Journal information: arXiv

Provided by Universe Today