What's keeping global biodiversity at bay?

An article in the journal Science Advances, published by scientists from Prague´s Charles University (Center for Theoretical Study and Faculty of Science), shows that the Earth's biodiversity is regulated on the scale of tens of millions of years by a feedback loop between diversity on the one hand and the origination and extinction of species on the other, so that it cannot grow indefinitely. This sheds new light on the current biodiversity crisis.

Life began almost 4 billion years ago, but we only have fossils that tell us more about its history from the last 540 million years. The question that has always vexed paleontologists and ecologists alike is whether biodiversity has grown steadily over that time, or whether there were limits to it, imposed by the limited capacity of the global ecosystem.

Early analyses suggested that the number of taxa did not change much during the Paleozoic, but after the largest extinction event at the turn of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras (a quarter of a billion years ago), diversity has steadily increased until the present day. This has started to be challenged in the last two decades, based on the idea that the apparent diversity increase might stem from the fact that the closer we get to the present, the more information we have about the past diversity of life. Some analyses have suggested that when these artifacts are removed, the Earth's biodiversity is quite stable, implying there is some mechanism that regulates it. The question remained how such a mechanism could work and whether it was universal.

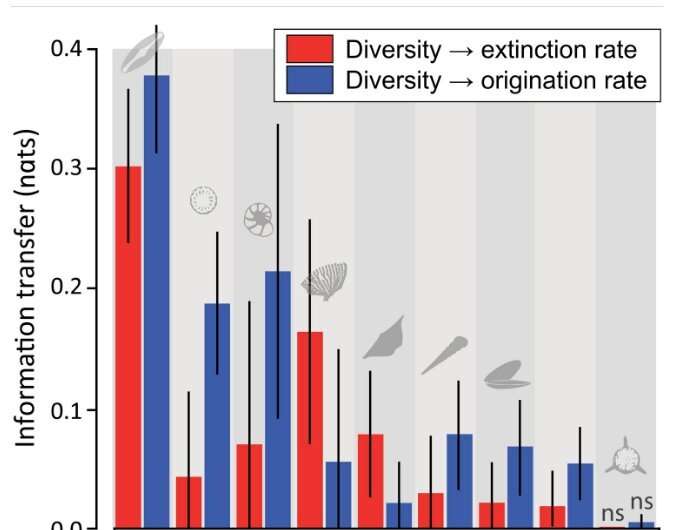

New light has now been shed on this by a study by Valentin Rineau, Jan Smycka and David Storch, a group working at the Center for Theoretical Studies, a joint institute of Charles University and the Czech Academy of Sciences. They asked what influences the observed appearance and disappearance of taxa in the fossil record. They analyzed the available fossil time series of nine groups of marine organisms (their time series are much more complete than those of terrestrial organisms) and used new statistical methods to determine whether environmental changes (temperature and resource availability) or diversity itself was responsible for these changes. They focused mainly on whether higher biodiversity in a given group leads to lower rates of origination of new taxa or to higher rates of their extinction. This would be the mechanism by which diversity is regulated.

The effect of environmental change has been shown to be highly variable and group-specific—some types of organisms respond to changes in temperature, others to changes in environmental productivity, and in other groups the emergence and disappearance of taxa in fossil time series is independent of environmental changes. In contrast, the effect of diversity is virtually universal—higher diversity leads to lower rates of origination and higher rates of extinction.

As a result, the Earth's overall biodiversity is kept within certain limits—the higher it is, the more likely it is to decrease in the next time interval. The authors speculate that this feedback mechanism is due to the fact that when the amount of resources on Earth is limited, an increase in the number of species is necessarily accompanied by a decrease in their population sizes. This then leads to a higher risk of extinction and a more difficult time for new species to become established.

The authors used state-of-the-art analytical techniques for their study, which, unlike traditional statistical methods such as regression techniques, can reveal the direction of causal relationships and uncover non-linear effects and lags. As a result, it has been shown that while the emergence of new taxa responds to changes in diversity in the very next period, extinctions are often delayed by up to several million years. "This has major implications for understanding the potential consequences of the current biodiversity crisis. It is possible that the current changes will have consequences for a very long period in the future," says David Storch, who, in addition to CTS, also works at the Faculty of Science at Charles University in Prague.

Most importantly, if the Earth's biodiversity is regulated by the limited amount of resources available to organisms, then any reduction in this supply of resources will necessarily lead to a reduction in the Earth's diversity. It is estimated that the human population consumes more than a quarter of the primary production of ecosystems (not to mention taking away space for wildlife), so it is hardly possible to maintain the same number of species on Earth as there would be without human appropriation of resources.

More information: Valentin Rineau et al, Diversity dependence is a ubiquitous phenomenon across Phanerozoic oceans, Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add9620, 36306361

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by Charles University