Physics models better define what makes pasta 'al dente'

Achieving the perfect al dente texture for a pasta noodle can be tough. Noodles can take different times to fully cook, and different recipes call for different amounts of salt to be added. To boot, sometimes noodles will stick to each other or the saucepan.

In Physics of Fluids, researchers from the United States examined how pasta swells, softens, and becomes sticky as it takes up water. They combined measurements of pasta parameters, such as expansion, bending rigidity, and water content to solve a variety of equations to form a theoretical model for the swelling dynamics of starch materials.

Author Sameh Tawfick, from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said exploring the properties of noodles was a straightforward pivot from the lab's main work of studying the fluid structure interaction of very flexible and deformable fibers, hairs, and elastic structures.

"Over the last few years, we joked about how pasta noodle adhesion is very related to our work," he said. "We then realized that specifically, the mechanical texture of noodles changes as function of cooking, and our analysis can demonstrate a relation between adhesion, mechanical texture, and doneness."

When the pandemic hit, the idea gained traction, and students and postdocs started working on it at home and in the lab.

The team observed how the noodles come together when lifted from a plate by a fork. This provided them with a grounding of how water-driven hygroscopic swelling affects pasta's texture.

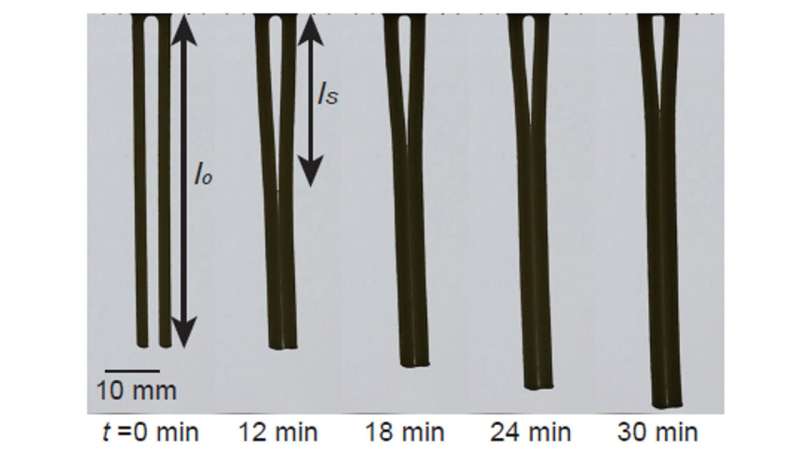

As pasta cooked, the relative rate of the noodle's increase in girth exceeded the rate of lengthening by a ratio of 3.5 to 1 until it reached the firm texture of al dente, before becoming uniformly soft and overcooked.

As pasta is pulled from liquid, the liquid surface energy creates a meniscus that sticks noodles to one another, balancing the elastic resistance from bending the noodles and aided by adhesion energy from the surface tension of the liquid.

The degree to which a noodle was cooked was directly related to the length of the portion that adhered to its neighbors.

"What surprised us the most is that the addition of salt to the boiling water completely changes the cooking time," Tawfick said. "So, depending on how much salt is added to the boiling water, the time to reach al dente can be very different."

Tawfick hopes the group's work inspires others to find simple methods for studying soft materials and looks to investigate the role of salt in swelling.

More information: Jonghyun Hwang et al, Swelling, softening, and elastocapillary adhesion of cooked pasta, Physics of Fluids (2022). DOI: 10.1063/5.0083696

Journal information: Physics of Fluids

Provided by American Institute of Physics