November 24, 2016 report

New study shows why heme-copper oxidases prefer copper over iron

(Phys.org)—A family of enzymes known as heme-copper oxidases (HCOs) plays a pivotal role in the reduction of oxygen into water during cellular respiration. One mystery surrounding heme-copper oxidases is why the non-heme metal center tends to be copper rather than iron.

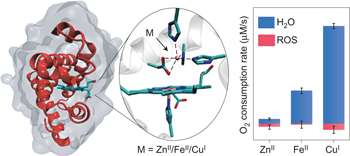

A group of researchers from the University of Illinois, Stevens Institute of Technology, and Oregon Health & Science University has developed a biosynthetic protein model system that replicates the active sites and many structural features of naturally-occurring HCOs. With their model system, they looked at the differences in the reduction of oxygen to water when the non-heme metal is iron versus when it is copper. They found that the non-heme metal plays a key role in electron donation and O-O bond cleavage and that it is likely copper's d-orbital electron configuration that causes its enhanced activity. Their work appears in Nature Chemistry.

"HCOs have been studied for more than half a decade now, but the selection of copper by nature at the nonheme center over other metal ions was not understood," says lead author Dr. Ambika Bhagi-Damodaran. "Our work is exciting because we finally resolve this long-standing question regarding the structure and function of this very important respiratory enzyme."

Their synthetic analog to the natural heme-copper oxidase is made from myoglobin, a small protein found in muscle that is a cousin to hemoglobin. Myoglobin has an iron-containing heme center and is denoted as FeBMb(FeII) because the heme iron is in the 2+ oxidation state. FeBMb(FeII) was produced and purified without a metal in the non-heme site using a previously reported procedure.

The empty FeBMb(FeII) was titrated with ZnII, which is not redox active and serves as the experimental control, CuI, and FeII. Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy confirmed that each metal was incorporated into the non-heme site. X-ray crystallography confirmed that each of these metal-FeBMb(FeII) variants exhibited similar active sites. In other words, this confirmed that the identity of the non-heme metal did not induce structural changes.

Bhagi-Damodaran et al. then investigated the differences in catalytic activity between the iron- and copper-containing species. They looked at reaction rate as well as product selectivity. Their enzymatic assay showed that FeII-FeBMb(FeII) and CuI-FeBMb(FeII) had 11-fold and 30-fold higher oxidase activity compared to the ZnII control and the FeBMb(FeII) without a non-heme metal.

Using electron paramagnetic resonance and X-ray near-edge spectroscopy, they determined that the non-heme CuI was oxidized to CuII and the non-heme FeII was oxidized to FeII, thus confirming that the non-heme metal plays a central role in oxygen reduction as electron donors. To further understand the difference between copper and iron, Bhagi-Damodaran et al. studied the standard reduction potentials (Eo') of FeIII/FeII and CuII/CuI at the model enzyme site. (The heme iron was replaced with a redox-inactive zinc protoporphyrin using a previously reported protocol.)

They found in both species a single reversible wave that corresponded to Eo' of 259 ± 20mV for iron and Eo' of 387 ± 25mV for copper. Since standard reduction potentials are related to the thermodynamic driving force of a reaction, copper's higher value means that CuII/CuI is more efficient at receiving electrons for the electrochemical reduction of oxygen to water.

The last step was to look at whether non-heme iron or copper interacts with heme-bound O2 to aid in cleaving the O-O bond. Using resonance Raman spectroscopy, the authors looked at the vibration of the O-O bond and found that the terminal oxygen atom interacts with the nonheme metal weakening the O-O bond. To test if the identity of the nonheme metal had any impact on O-O bond length, the authors performed Density Functional Theory calculations and found that O-O bond length was longest in CuI-FeBMb(FeII). These results showed that the non-heme metal plays an important role in activating the oxygen molecule and facilitating O-O cleavage.

The preference of HCOs for copper is likely due to the higher redox potential of Cu as well as its d-orbital electron configuration. Copper-II has nine d-electrons, while FeIII has five d-electrons. This additional electron density gives copper the advantage in orbital interactions with oxygen's highest occupied molecular orbitals.

Overall, this work provides important insights into naturally-occurring heme-copper complexes. According to corresponding author Professor Yi Lu, "We anticipate our work to be a starting point for more focused efforts toward using different metal ions at the non-heme site for various biochemical reactions. This pursuit can aid the design of novel catalysts required in alternative energy technologies and other biotechnological applications."

More information: Ambika Bhagi-Damodaran et al. Why copper is preferred over iron for oxygen activation and reduction in haem-copper oxidases, Nature Chemistry (2016). DOI: 10.1038/nchem.2643

Abstract

Haem–copper oxidase (HCO) catalyses the natural reduction of oxygen to water using a haem-copper centre. Despite decades of research on HCOs, the role of non-haem metal and the reason for nature's choice of copper over other metals such as iron remains unclear. Here, we use a biosynthetic model of HCO in myoglobin that selectively binds different non-haem metals to demonstrate 30-fold and 11-fold enhancements in the oxidase activity of Cu- and Fe-bound HCO mimics, respectively, as compared with Zn-bound mimics. Detailed electrochemical, kinetic and vibrational spectroscopic studies, in tandem with theoretical density functional theory calculations, demonstrate that the non-haem metal not only donates electrons to oxygen but also activates it for efficient O–O bond cleavage. Furthermore, the higher redox potential of copper and the enhanced weakening of the O–O bond from the higher electron density in the d orbital of copper are central to its higher oxidase activity over iron. This work resolves a long-standing question in bioenergetics, and renders a chemical–biological basis for the design of future oxygen-reduction catalysts.

Journal information: Nature Chemistry

© 2016 Phys.org