The universe's primordial soup flowing at CERN

Researchers have recreated the universe's primordial soup in miniature format by colliding lead atoms with extremely high energy in the 27 km long particle accelerator, the LHC at CERN in Geneva. The primordial soup is a so-called quark-gluon plasma and researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute, among others, have measured its liquid properties with great accuracy at the LHC's top energy. The results have been submitted to Physical Review Letters.

A few billionths of a second after the Big Bang, the universe was made up of a kind of extremely hot and dense primordial soup of the most fundamental particles, especially quarks and gluons. This state is called quark-gluon plasma. By colliding lead nuclei at a record-high energy of 5.02 TeV in the world's most powerful particle accelerator, the 27 km long Large Hadron Collider, LHC at CERN in Geneva, it has been possible to recreate this state in the ALICE experiment's detector and measure its properties.

"The analyses of the collisions make it possible, for the first time, to measure the precise characteristics of a quark-gluon plasma at the highest energy ever and to determine how it flows," explains You Zhou, who is a postdoc in the ALICE research group at the Niels Bohr Institute. You Zhou, together with a small, fast-working team of international collaboration partners, led the analysis of the new data and measured how the quark-gluon plasma flows and fluctuates after it is formed by the collisions between lead ions.

Advanced methods of measurement

The focus has been on the quark-gluon plasma's collective properties, which show that this state of matter behaves more like a liquid than a gas, even at the very highest energy densities. The new measurements, which uses new methods to study the correlation between many particles, make it possible to determine the viscosity of this exotic fluid with great precision.

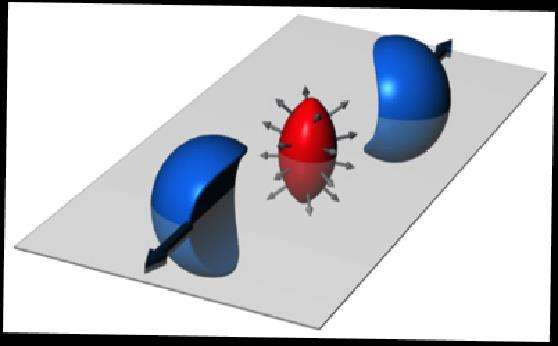

You Zhou explains that the experimental method is very advanced and is based on the fact that when two spherical atomic nuclei are shot at each other and hit each other a bit off center, a quark-gluon plasma is formed with a slightly elongated shape somewhat like an American football. This means that the pressure difference between the centre of this extremely hot 'droplet' and the surface varies along the different axes. The pressure differential drives the expansion and flow and consequently one can measure a characteristic variation in the number of particles produced in the collisions as a function of the angle.

Mapping the primordial soup

"It is remarkable that we are able to carry out such detailed measurements on a drop of 'early universe', that only has a radius of about one millionth of a billionth of a meter. The results are fully consistent with the physical laws of hydrodynamics, i.e. the theory of flowing liquids and it shows that the quark-gluon plasma behaves like a fluid. It is however a very special liquid, as it does not consist of molecules like water, but of the fundamental particles quarks and gluons," explains Jens Jørgen Gaardhøje, professor and head of the ALICE group at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

Jens Jørgen Gaardhøje adds that they are now in the process of mapping this state with ever increasing precision—and even further back in time.

Journal information: Physical Review Letters

Provided by Niels Bohr Institute